When my first sister told me that her adolescent son had discovered David Bowie, something powerful struck me. My nephew, I realized, had joined the legion of outsiders. He had recognized (on some level) that the world was a complicated place, that in the inescapable realms of majority rule, you usually don’t get to choose to be on the winning team, and that often times the winning team isn’t even one you’d want to join.

Watch any vintage news feature on Bowie fans—they’re not hard to find, the media has long loved teen freak shows—and you’ll see a parade of young people celebrating their outcast status. For many, most, (all?) of us, insecurity comes with the territory of adolescence, and there are different ways of dealing with it, from bullying on the one end to seeking remote solace on the other. For me at my nephew’s age, as for so many, David Bowie offered solace. He represented the possibility of realizing potential. His music was sex and drugs and rock and roll to be sure—and seemingly any sex and any drugs would do—but it wasn’t just that. It was about, seemingly literally, reaching for the stars.

What went hand in hand with reaching for the stars was Bowie’s preaching to the perverted. Bowie fans were outsiders. It didn’t matter if it was sexual preference, gender identification, addiction, skepticism or just feeling smarter than the other kids in class, Bowie fans fell and fall outside the norm. He spoke to kids who felt like they didn’t fit in. He was, as he suggested on his career-defining The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, their leper messiah. Bookending that album are songs that proclaim “Your face, your race, the way that you talk / I kiss you, you’re beautiful, I want you to walk” and “Just turn on with me, and you’re not alone / Gimme your hands, ’cause you’re wonderful.” The “you” was both collective and singular. It was a direct invitation to the anointed listener. When Bowie embraced mainstream success in the ‘80s, it was with more than a decade of loving the alienated behind him.

I heard what may have been the first public announcement of Bowie’s death, up late listening to BBC radio news in the early hours of January 11, 2016. Among my first thoughts were to text my sister so that she could break it to her son, then 15, before he heard it on the news the next morning. I did so, then poured another drink and put on Bowie’s Blacktar, the album I’d had on rotation in the two days since its release, and thought of my own early days discovering the work and worlds of David Bowie.

⚡ ⚡ ⚡

Lodger was the first Bowie album I bought, foisted upon me by a record store clerk whom I held in idolized reverence, at around the same age my nephew was when he discovered David Bowie. It’s also the first album (of three, so far) that producer/bassist Visconti has remixed since Bowie’s death. It was initially included in the 2017 A New Career in a New Town, the third in a series of career retrospective series box sets, part of a steady stream of new product in his wake; this month sees the release of a 7” single with never before released Bowie covers of Bob Dylan and John Lennon, limited for some reason to 8,147 copies. I had avoided the box sets and it was the new Visconti mix that pushed me over the edge, dropping something over $100 for a copy of my own. While I relished in the packaging and the perks designed to materialize and thus monetize nostalgia, I was not a fan of the new mix. It was too pushy, I thought, too amped up. It didn’t have the sound of that paper-thin RCA vinyl played on the mid-grade department stereo system of my youth.

Listening again now, I’m no longer offended by the enhanced audio. Like the two albums Visconti has since remixed (known as Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold the World, although oddly enough both have been released under multiple titles), his Lodger is bright, detailed and faithful. But at the time, I didn’t want Visconti getting in between Bowie and me. The box set was released 20 months after Bowie’s death. I had been reassured to learn that Bowie and Visconti discussed the remix, and that Bowie had heard and approved of some of it, during his work-filled final months. But when it got to my ears, it felt as if someone were trying to rewrite my memory. This was not the way Lodger sounds, and I am not 14 years old playing it at ridiculous volumes in my parents’ house.

In truth, Lodger isn’t one of Bowie’s strongest albums. A concept album without a storyline, the record is a series of scenes of transients, stories of detachment, migration and unsatisfying occupations. Bowie’s alienation had grown adult. The title even suggests as much. And in fact, none of the albums Visconti has reworked thus far are among Bowie’s very best. But I’ll always hold Lodger close to my heart, not just as my first Bowie record but among my first grown-up albums.

⚡ ⚡ ⚡

The two other records Visconti has remade and remodeled—1969’s David Bowie (aka Space Oddity) and 1970’s The Man Who Sold the World (now released under its intended title, Metrobolist)—also fall just short of Bowie’s Top 5. To these long-listening ears, those would be Station to Station, Low, “Heroes,” Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) and Blackstar—all but the first of which Visconti had a hand in the making. But of course personal preference is nothing more than personal preference, and with Bowie, it can be very personal. But good Bowie easily bests many artists’ bests. (Station to Station, for the record, got a worthy touch-up by co-producer Harry Maslin in 2010.)

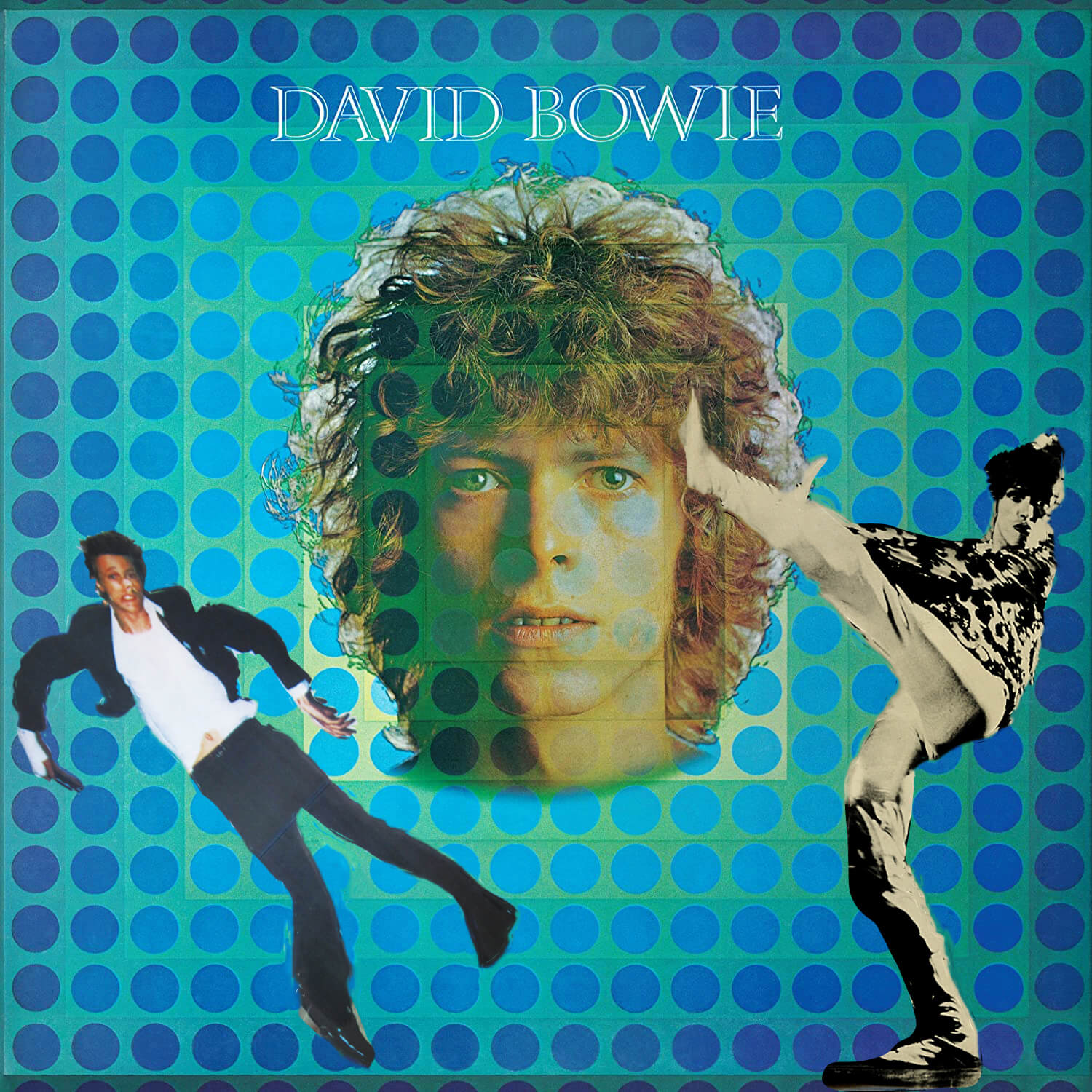

Visconti’s Space Oddity (released in 2019) restores the original cover art but retains the title that was tacked on to capitalize on the recent moon landing. It had originally, and rather oddly, been released as his second eponymous album in a row, following the quaint, cabaret pop of his debut. The new issue adds the track “Conversation Piece” but drops the brief “Don’t Sit Down.” It is, in other words, more hodgepodge than definitive, saved by Visctonti’s sound salvation. The cleaner reverb on the acoustic guitar intro of (what remains) the title track make the crisp guitar break later so much more distinctive. The clarity throughout, especially in the bass (and Visconti, of course, is a bassist, although here on flute) and in the reediness of the electric organ in “Memory of a Free Festival,” are a revelation.

The Man Who Sold the World always suggested an early Pink Floyd influence to me—indeed, “All the Madmen” could be as much for that band’s troubled co-founder Syd Barrett as for Bowie’s own schizophrenic half brother. It is also one of Visconti’s favorite Bowie albums, as he notes in the liner notes to the Five Years (1969–1973) box set. “It is dark and foreboding,” he says, “heavy, no love songs, nothing really cute about it.” The punch Visconti adds to the mix for the reissue (released in November, 2020, as Metrobolist) brings out that darkness: it now sounds closer to early Sabbath than tired Zeppelin. With the added oomph, it may be his most rocking—certainly more so than the comparatively flat Orwellian montage Stones homage Diamond Dogs, which falls with more thuds than any record of his before the go-go 80’s. The Metrobolist mix accentuates the heavy trio at the album’s core: Visconti on bass with Mick “Woody” Woodmansy on drums and someone who would become one of Bowie’s most important collaborators, Mick Ronson, on guitar. With Visconti swapped out for Trevor Bolden, that band would soon transform into the Spiders From Mars as Bowie morphed into Ziggy Stardust.

As with Space Oddity, it’s not quite a restoration to anything in particular. The original cartoon cover used here was not Bowie’s choice at the time (alternate covers were used for the original U.K. and U.S. releases). The running order remains the same, although a sequence purportedly proposed by Bowie and discussed on fan sites makes more sense (set your playlist to: 9, 6, 5, 7, 8, 3, 1, 2, 4 to hear that one). The new mix, however, again justifies the haphazard presentation.

⚡ ⚡ ⚡

No one can rewrite your memories, of course, at least not yet. A new mix of a beloved record is just an invitation to listen anew. In truth, I didn’t A/B the Visconti mixes against previous releases. I just went by memory. And I’ve (literally) bought in, the records given added value by my desire not to have wasted money buying something I already have several copies of. I instead accept an old experience as new again, something to be appreciated, relived, reloved. Memories fade, but albums are forever.