Paulie McDonald is looking for striped bass tonight.

“They’re the biggest, meanest thing out here,” says McDonald, “and that’s what I’m trying to catch.”

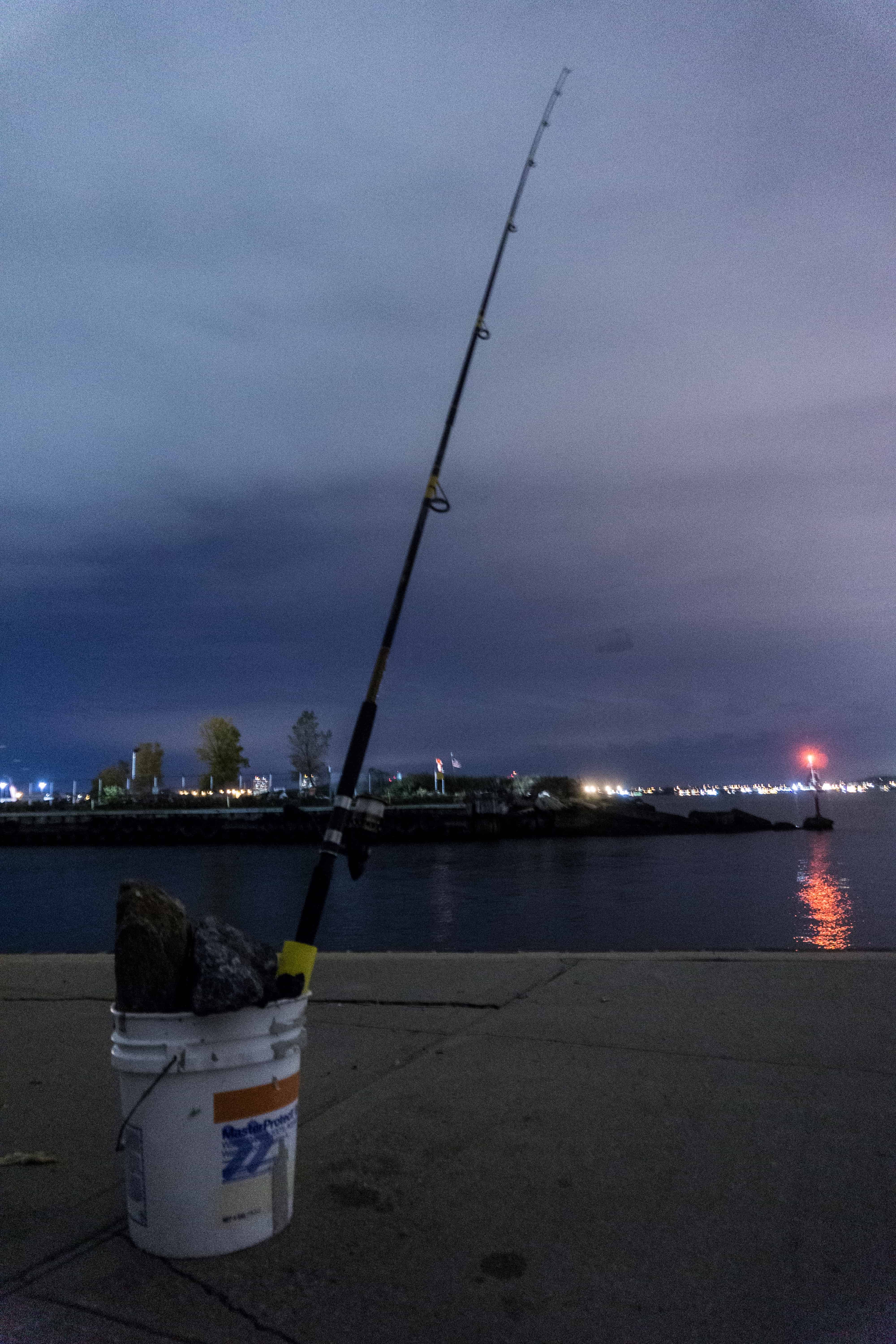

McDonald is standing on a crumbling concrete bulkhead behind one of the long brick warehouses that define the Red Hook landscape. Even as he speaks, McDonald’s eyes are fixated on the tip of the fishing rod planted in the bucket in front of him. It’s around 1 in the morning in late October, and a bit chilly.

“The fishing gets pretty good this time of year, but it’s cold, so you’ve got to be kind of diehard,” says McDonald, who is 32 and has a construction shop in Red Hook. “I’ll come out, I’ll suffer. A little bit of weather isn’t going to stop me.”

McDonald and his friends have been fishing in Red Hook for more than ten years. Until recently, they caught a huge diversity of fish, from bait like bunker and minnows to larger game fish like herring, bluefish, blackfish, fluke, and striped bass. But in early October, the ecology of Erie Basin was disrupted when work began at a new development on site of the old Revere Suger Refinery. Per the local fishermen, the work has clouded the water and possibly released long-encapsulated toxic materials into the water column.

“I go down there every day and I see what they’re doing, and how they’re doing it, and it just bothers my mind,” says Robbie Giordano, another local fisherman and neighborhood barman. “I haven’t seen any dead fish floating yet – that’s because most of them are smart enough that they get a taste of the water and they get out of there.”

Erie Basin

Look at a map of Red Hook, and Erie Basin immediately draws the eye. Roughly 90 acres in area, it is formed by the artificial peninsulas of Van Brunt Street on the west side and Columbia Street on the east side. The basin also separates the Buttermilk Channel to the east and Gowanus Bay to the west.

Erie Basin was built in the 1840s by William Beard and Jeremiah and George Robinson as an offloading point for goods coming down the Erie Canal from the Midwest. It was a major part of what made Red Hook – and New York – one of the biggest shipping centers in the world.

“Erie Basin is very deep in some places because it was created to use as ship dockage. There were ship repairs there, there was off-loading of rice, grains, sugars, big ships with deep hulls would need to go in there,” says Giordano, who has lived in Red Hook for the last ten years and has fished Erie Basin for the last eight. “A lot of people don’t know this, but Erie Basin actually has an opening on both ends.”

Giordino, 45, has been fishing since he was two years old. He majored in Fisheries and Marine Technology at Kingsboro College, and worked for the New York Water Taxi until a traffic accident put him behind the bar at Verona Lounge. He says that Erie Basin’s natural geography makes it one of the best spots in New York Harbor to fish.

“Erie Basin has been a tremendous source of life in terms of fish ecology and bird ecology,” says Giordano. “The water quality used to be probably the highest of any as far as clarity, oxygen levels, and condition overall than anywhere else in New York Harbor.”

“Erie Basin has been a tremendous source of life in terms of fish ecology and bird ecology,” says Giordano. “The water quality used to be probably the highest of any as far as clarity, oxygen levels, and condition overall than anywhere else in New York Harbor.”

He says that clear ocean water is pushed along the southern shore of Brooklyn, flushing Erie Basin every 12 hours with the tide.

”You can actually see it happening. You see chocolate milk on one side and this greenish clear water moving against it on the other side,” says Giordano. “There’s a deep channel that comes all the way from the Breezy Point jetty along the Belt Parkway, all the way along Brooklyn. The first relief point is Erie Basin.”

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) designates parts of Erie Basin as a Priority Marine Activity Zone as well as a Significant Maritime Industrial Area. The IKEA site, formerly a U.S. Dredging Shipyard Site, was restored as part of DEC’s Brownfield Remediation Program.

Rodney Rivera, who works at DEC’s Long Island City office, also says that Erie Basin is prime real estate for many forms of life.

“The marine ecology of Erie Basin is productive for seaweed, barnacles, and possibly oysters due to restoration projects. It also has rocky, shallow, inter-tidal, and deep water habitats, which are used by many forage fish to feed and hide from valuable predatory fish,” writes Rivera in an email to the Star-Revue. “The predatory juvenile fish also use the habitats to hide from larger predatory fish.”

McDonald puts it in simpler language.

“We’re in New York City, but I’m in sort of my own personal space right now, away from all the millions of people that drive me crazy on a day-to-day basis. I’m looking at the Statue of Liberty. I’m looking at the Verrazano Bridge. I’m looking at New Jersey, and no one can really bother me here,” says McDonald, his eyes still on his rod. “It’s basically as close to nature as I’m going to get, and I’m right here in New York City. It’s a pretty beautiful thing.”

False Albacore

McDonald and his friends usually purchase or catch bait in the afternoon, and meet at their spot after dark – often after Giordano closes the bar. Depending on how good the fishing is, they might stay out all night.

“I’ll stay out till five in the morning, I’ll sleep on the concrete for an hour, get up, and go straight to work,” says McDonald. “I’ll be there by 8 o’clock, covered in fish blood and ready to knock out some construction.”

McDonald says that it’s rare to find a fishing community that so respects Mother Nature.

“Especially in New York City, guys just come out and poach fish. Anything they catch, they’re gonna keep,” says McDonald. “We respect the rules, and put back fish that are under limit or out of season. We pray to the fish gods, really, and that’s what makes a fishing community. Respect for a higher power.”

back fish that are under limit or out of season. We pray to the fish gods, really, and that’s what makes a fishing community. Respect for a higher power.”

In early October, Giordano saw something special as he made his rounds, something he had never seen before.

“I’m going to scout for bait, and I see these explosions on the surface. It was as if someone was dropping 9-pound, 10-pound bowling balls into the water,” says Giordano. The explosions were moving quickly, and following a school of small bunker, leading Giordano to induce that the “explosions” were caused by a species of tuna often called false albacore.

“It was amazing. It was amazing to see them in Erie Basin. That is a sign of water quality and available food source, and all those elements coming together,” says Giordano. “If I had hooked and landed a false albacore in Erie Basin from the shore, I guarantee that would have been the first time it had ever happened [since the Industrial Revolution]. Guaranteed. And I came within inches of doing it.”

But things changed quickly at Erie Basin.

“The very next day when I went there, it was as if I had walked through a door into the desert – coming from a rainforest, coming from the jungle,” says Giordano. “I’m looking around, I don’t see anything, I don’t hear anything – I can smell the bunker when they’re there, I don’t smell anything.”

Work had begun on Red Hoek Point, a new development by Thor Equities on the former site of the Revere Sugar Refinery, just to the east of IKEA.

“They’re really going hard over there. They’re disturbing things so much. They’re digging down so deep, and they’re pulling up so much stuff,” says Giordano, pointing at the cloudy water of Erie Basin. “All the silt, and the muck and the layers that have been enclosed – as they bucket that stuff up, half of it just blows out, gets directly injected into the water column and stirred around by the current, and just settles back down on top of everything that’s alive. It kills everything. It’s toxic materials and heavy metals that now are exposed.”

Since the work began, Giordano and his friends have not been able to catch any of their bait, and the game fish also have dropped off.

“This time last year I would see three or four big schools of bunker on a daily basis,” says Giordano. “I’ve been there every day since the construction started. Since then, there have been no visible signs of life except a little bit here a little bit there.”

“There’s a mussel bed out there where all the fluke and flounder go in the summertime. All those mussels are going to probably die – or become contaminated,” adds Giordano, “I can’t watch it for more than five minutes. I get disgusted to see what’s going on.”

Richards Street Bulkhead

“Red Hoek Point will include two heavy timber frame buildings with 23,000 square feet of retail and restaurant space, and more than 795,000 square feet of creative office space on three levels,” says Thor Equities’ website. “The campus also features a public waterfront esplanade and open courtyard.”

But before work can commence on buildings, Thor Equities must restore the bulkheads on its site, which juts around 700 feet into Erie Basin.

“We are installing a new steel sheet pile bulkhead around the entire perimeter of the property to replace the failed and decaying timber bulkhead,” writes Thor Equities spokesman Joshua Greenwald. “The old timber cribbing is being removed in order to drive the new steel sheeting.”

The site at Richards and Beard Streets, formerly known as the Richards Street bulkhead, was used for sugar refining since before World War I.

“By 1915, some of the property was in use by the American Molasses Company; by 1931 all of it was,” wrote Thomas Flagg in 1991 when the city was considering acquiring the refinery as a cultural and historic landmark. “Sugar refining was once a major component of Brooklyn’s industry, with major installations in several areas. The Revere site was probably the last of these.”

The Revere Sugar Refinery was in continuous use until at least the mid 1980s, when the company went bankrupt. The building was purchased by Joe Sitt of Thor Equities in 2005 for $40 million and demolished throughout 2007-2009. In 2015, Thor Equities announced its plans to build Red Hoek Point.

Although Thor Equities has permits for its work in Erie Basin and DEC’s Rodney Rivera says that the work should not be causing any pollution, Red Hook’s fishing population and others report a significant drop in water quality since the work began.

Mike McCann, an Urban Marine Ecologist who works with the Nature Conservancy, says that it’s likely the fish have moved to other areas in the harbor.

“Fish and other marine organisms are attracted to structure in the water, but if you disturb that structure, they’ll go elsewhere,” writes McCann. “Those animals are probably not dead – just attracted to some other structure nearby. So if you stop construction or add new structure, it will attract life again.”

Giordano says that if Thor Equities has all of the permits, the approval process cannot have been stringent enough. DEC did not respond to email asking about the approval process.

“I don’t know if it’s legal or illegal, all I know is that there was this very unique ecosystem that’s been undone,” says Giordano. “No one bothered to look at what was going on here before they just said ‘go-ahead, build this, dig this up.’ This should be a protected area. It should be a protected ecosystem. It should be a fish haven, and no one looked at it like that.”