Visitors can have a magical time at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, thanks to a limited time-only exhibit that connects classic twentieth-century century Walt Disney films with eighteenth-century European history and artwork.

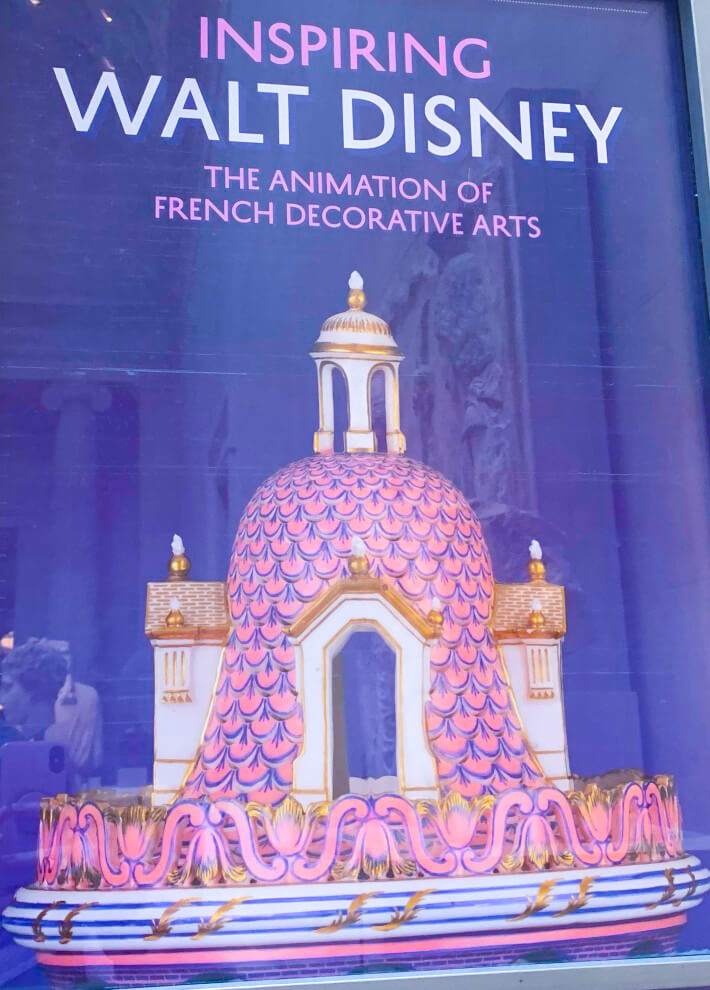

Nestled between the Greek and Roman Art gallery and the European sculpture and decorative arts gallery is “Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts,” the first-ever exhibition at The Met to explore the work of Walt Disney and the hand-drawn animation of Walt Disney Animation Studios. It allows museum goers to learn not only about Disney’s captivation with eighteenth-century European decorative art, but how it inspired him and his production teams to create some of the most recognizable movie stills. The exhibition also marks the 30th anniversary of Beauty and the Beast (1991), which was the first animated feature film to be nominated for “Best Picture” at the Academy Awards in 1992.

Spread out across more than five gallery rooms are 60 works of eighteenth-century European decorative arts and design—as well as artifacts from the Met’s collection (such as Jean Honoré Fragonard’s “The Swing” [1768], Juste Aurèle Meissonnier’s bronze candlesticks [ca. 1745]), and “The Unicorn Tapestries” [ca. 1495-1505]—and 150 production artworks (like concept art and framed cels) from the Walt Disney Animation Research Library, Walt Disney Archives, Walt Disney Imagineering Collection, and The Walt Disney Family Museum.

“Visiting The Met Cloisters in the early 1950s, John Hench, a versatile and highly influential Disney artist who later became a central figure in designing Disneyland, was awed by the tapestries’ bustling scenes and proposed them as a visual template for “Sleeping Beauty,’” read one of the in-gallery labels.

Disney, who was born and raised in Chicago, was first introduced to European culture when he visited France for the first time in 1918 at the age of 16. The buildings and art that he saw across Western Europe during his visit in the summer of 1935 (especially in Paris where the Disney family saw King Louis XIV’s old home, Marie Antoinette’s “little house,” and the room where the Peace Treaty was signed) remained with him, inspiring and influencing the work he would create until his death in 1966. Gothic Revival architecture, for example, can be found in Cinderella (1950), and medieval influences are most apparent in Sleeping Beauty (1959)—which is considered “one of the artistically most sophisticated of all Disney films,” according to Wolf Burchard, the exhibition’s curator.

“In mounting The Met’s first-ever exhibition devoted to Walt Disney and his studios’ oeuvre, it was important for us to explore his sources of inspiration as well as to recognize that his studio’s animated interpretations of European fairytales have become a lens through which many view Western art and culture today,” stated Burchard ahead of the exhibition’s opening in early December 2021.

The Beauty and the Beast ballroom—complete with chandeliers, ceiling-to-floor windows, and a beautifully painted ceiling—drew inspiration from the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, Jean Honoré Fragonard’s “Swarm of Cupids” (ca. 1765-77) at the Louvre, and Jean Honoré Fragonard’s cherubs in “The Progress of Love” (1771-72) at the Frick Collection in New York. Inanimate Rococo-inspired objects with curves, pastel colors, and gold features, like teapots, candlesticks, and clocks, were also brought to life in the movie after the Walt Disney Studios began its Rococo-related research in 1988.

“By looking at the original reference of the French decorative arts, and then being able to caricature those and simplify those into an animatable object, was a real tribute to the character designers who were able to come in and make than happen,” says producer Don Hahn in a pre-recorded portion of the exhibition’s audio guide.

“Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts” will be on view until March 6, before traveling to London’s Wallace Collection.