Our tech-dominated society is generous with its glimpses of dystopia. But there’s something especially chilling about the captive audience meetings in the documentary Union, which screened at the New York Film Festival and is currently playing at IFC Center.

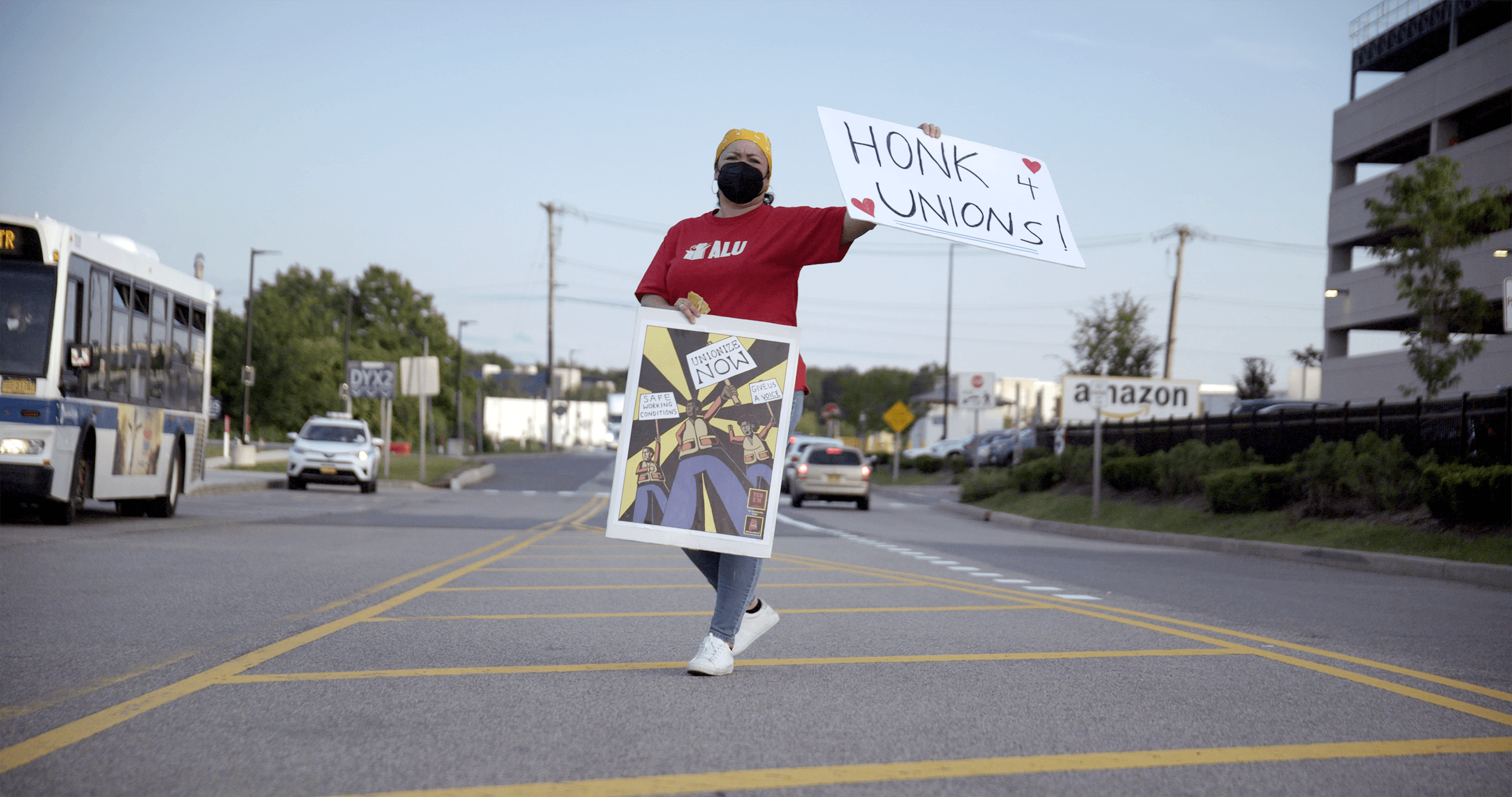

Chronicling the fight of the Amazon Labor Union (ALU), led by Chris Smalls, to organize the Amazon fulfillment warehouse in Staten Island, co-directors Brett Story and Steve Maing show us what it’s like inside. Workers at conveyor belts mechanically keeping packages moving. workers asleep in break areas. In one case, a worker bundling up to sleep in her car, her home for the last three years, parked in a warehouse garage. Experiences like these fuel the ALU, which Smalls began after being fired in 2020 for leading a walkout protesting conditions at the height of the pandemic.

While the scenes of Smalls and his small team of organizers hustling for support and votes are heroic, it’s Amazon’s reactions that are most eye opening — especially the anti-union indoctrination sessions led by union-busting consultants. About 15 minutes into the film, a worker captures shaky phone footage as she’s pulled from her job on a line surrounded by heavy machines, led through industrial corridors, and deposited into a conference room. A video implores her and her colleagues to reject the ALU. “We’re proud of our track record together,” says a disconcertingly cheery, and mildly threatening, male voice. “The ALU has no track record. They never represented any employees anywhere. All they have is promises. But they can’t guarantee anything. We’re asking you to do three simple things: Get the facts, ask questions, and vote no to the union.” It’s an absurd Orwellian moment that wouldn’t be out of place in THX-1138. And if the patrician message weren’t clear enough, later an actual human actually says, “We don’t feel like you need representation.”

The ALU ultimately won its election in April 2022, which Amazon steadfastly refuses to recognize and continues challenging in court — along with every other unionization effort confronting its various interests. But what makes Union vital is the journey to that victory. This is living history, a warts-and-all inside look at the contemporary labor movement, its challenges, and its opportunities. It’s a necessary piece of documentary filmmaking that will only grow more important as Amazon and companies like it tighten their grip on their employees’ rights to organize.

Co-director Maing spoke with the Star-Revue about the film and what it has to say to us now and in the future. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You and your team were there for, essentially, the start of this organizing campaign. That seems extraordinarily rare.

I feel like the way things go is, you’ll see a group of people start to come together and slowly understand what their capacity and their potential and, really, what their goals are. Before Union, I had been filming Crime + Punishment, a project about New York’s NYPD whistleblower cops. This group of minority active duty officers had come together to gather evidence to prove the policing practice in New York City was structurally biased and racist and that they were being pressured to meet a productivity quota for summons, arrests and stops. That movement was many years in the making. I had spent, like, three years getting to know these cops and then making a few different shorter projects before gaining greater access to be able to film this entire effort for them to wage this class action lawsuit against the NYPD. That was an additional four years. I think there was something very similar in the process of Chris and his cohort taking the year to kind of organize and push back against Amazon and call out Jeff Bezos’ practices before then deciding, “You know what, we could actually form a union here.” Brett Story and cinematographer Martin de Chico came into this in the spring of 2021, and I came on as co-director shortly after that, and we were basically in place from day one to document the entire campaign. That’s rare.

Recently, Amazon responded to a National Labor Relations Board complaint by saying, “All the statements Amazon allegedly made to [Delivery Service Partner] employees were protected by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.” Does it surprise you that Amazon would say they have a constitutional right to union bust?

When they don’t get their way, these corporations really behave no better than a petulant child. When you look at the efforts of SpaceX, Trader Joe’s, Amazon to sue the NLRB under the guise of a claim that it is unconstitutional in its practices,, the common factor of those companies is that they have all received reprimands from NLRB for firing and retaliating against workers who have tried to unionize. That’s a really a powerful linkage, and we have to kind of take stock of the fact that these companies will stop at nothing to stop the unionization wave. We saw Amazon spend about $14.2 million to try and stop the Amazon Labor Union. They employed countless labor consultants, who, as we know, are essentially just union busters, to populate the various warehouses where unionization efforts have popped up. The tactics have not changed, largely, since the Pinkertons almost 100 years ago. So it’s a really remarkable moment to see that an organizing group of, like, no more than 10 people with a crowdfund of maybe $125,000 was able to defeat a multi-million dollar effort in union busting. That’s grassroots organizing. That’s people saying we’re not going to organize in the traditional way. We are going to lean on the NLRB for all of its remaining power and capacity to protect these efforts.

There’s a tension in the nation — captured in the film — between the kind of worker-led effort of the ALU and one where a national, established union takes the lead. In Staten Island, worker-led organizing worked, but at the Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, a high-profile effort failed. What does Union have to contribute to this larger debate about how to organize in the 21st century?

The ALU didn’t operate entirely without any support from the established unions. The UFCW, SEIU, Teamsters — they were there, and you can see them in the background of the campaign as the ALU is trying their best to fend off Amazon’s efforts to break their organizing. But I think the problem is that there are a lot of questions about, can Chris Smalls, or the cohort of the ALU, pull this off? There was a lot of hedging that also happened, even though the established unions did lend some material and actual support.

We’re at a moment where Amazon workers are the center of the contemporary labor movement. It is minority, Black, Brown, and immigrant workers who have to not just be acknowledged but have a say in how their organizing campaigns run and the best ways to reach workers like them. As we see in the film, they never really got that confidence or sense of even trust that they themselves understood how to best reach their co-workers, who they shared lived and work experiences with. We have to take stock of being at a moment where now those workers are coming into their own. Their understanding, their political capacity and power, are the linchpin in taking on this kind of rampant, egregious, racial capitalism that we’re seeing explode in such highly extractive and dehumanizing ways.

What is the best way for established unions to support and not usurp these campaigns? To help them grow and scale up, as opposed to being offered to join and simply merge into a larger effort? How to lend support that doesn’t make grassroots organizers feel threatened by the possibility of losing control of their campaign? These are the really big questions I think the established unions need to be asking themselves.

I come from a United Steelworkers household, and a union was as natural as breathing. But that tradition has been dismantled. There is greater interest in unionization now than anytime in the last 30 years, yet barriers to forming and joining a union are getting steeper. What does that say about the state of unions?

Of course we’ve seen a decline in union density over the last 50 years, and I think we have to take stock of that. A lot of people, a lot of workers, today don’t necessarily have a lot of familial or direct generational experience with unions or unions that have felt equitable and beneficial? I think there’s been a slow decline, not just in density, but also in perception of what unions offer and what they do and don’t do for workers. It doesn’t help that we live in a highly politicized moment, where we have one party that has hedged at times in its support of unions and another that entirely just pantomimes its pro-worker stance. But there is a unionization resurgence that’s happening, and I think we’re at this really exciting moment.

Union is screening at IFC Center through November 7. More information about future dates and streaming options is available at unionthefilm.com.