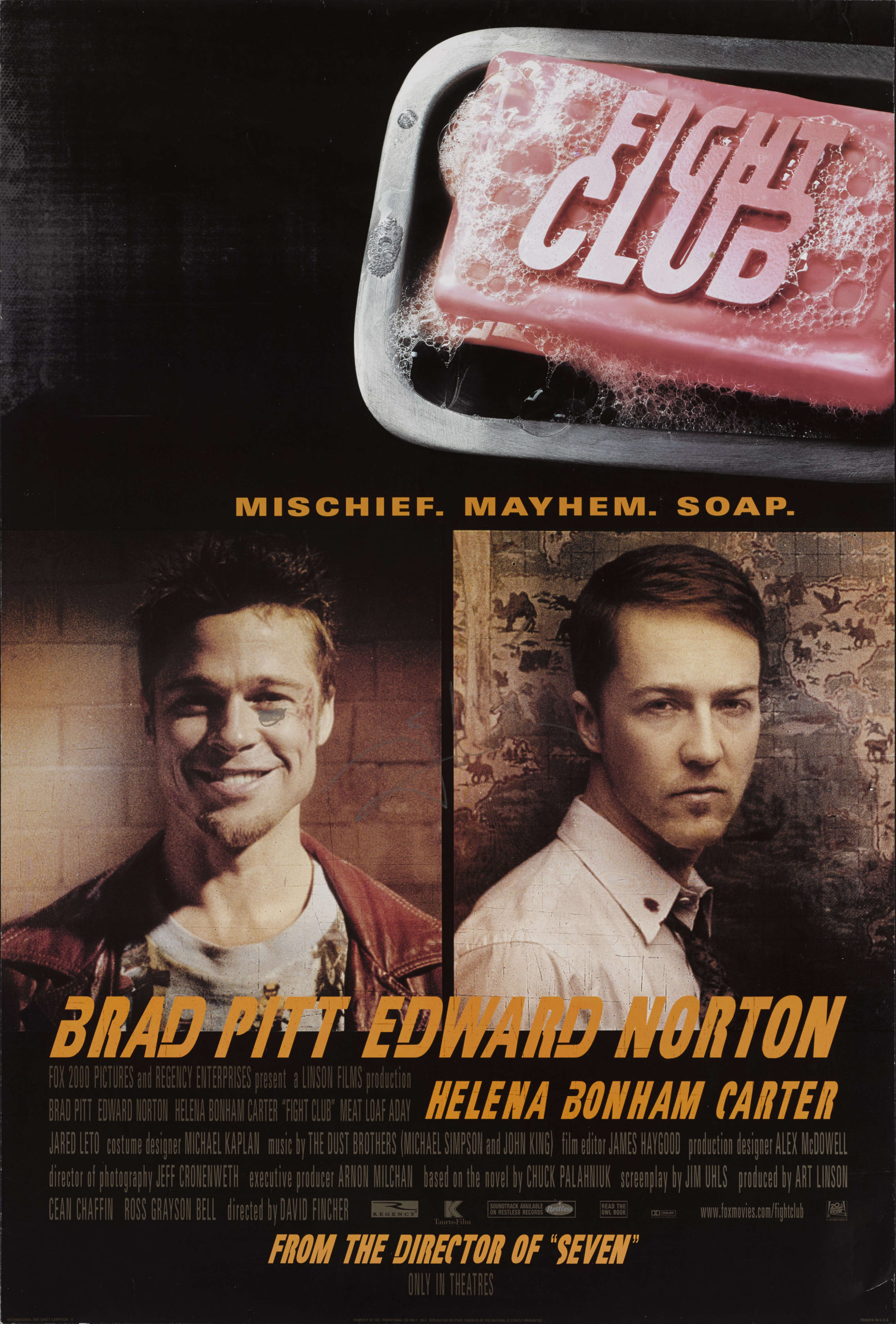

A strange Vice headline recently crossed my feeds: “Cult Classic ‘Fight Club’ Gets a Very Different Ending in China.” Thanks to Tencent Video, Fight Club, director David Fincher’s searing adaptation of Chuck Palahniuk’s novel, finally made it to China! Only took 22 years. Thing is, it also came with a new finale.

If it’s been a while, a quick refresher: The Narrator (Edward Norton) and Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) start up an underground fight club, attracting men like themselves who feel disaffected and cast off by an increasingly inhuman and debased consumer-capitalist culture. The club expands, spawns national franchises, and leads Tyler to think bigger and bolder. Fight Club becomes Project Mayhem, a series of increasingly destructive acts culminating in a plot to destroy America’s credit card companies. “If you erase the debt record, then we all go back to zero,” the Narrator tells police when trying to stop the plan. “You’ll create total chaos.”

Fight Club ends with the Narrator and girlfrenemy Marla (Helena Bonham Carter) watching bombs topple one skyscraper after another. It’s an indelible image and a fitting conclusion to Fincher’s grungy, puckish middle finger to conventional studio filmmaking. (It was released by 20th Century Fox, which is now owned by Disney. I wonder if it’s quarantined from the middlebrow junk in the Mouse’s vault.) But what Chinese viewers got was wholly different. After the Narrator shoots himself in the mouth (long story), the film fades to a title card: “Through the clue provided by Tyler, the police rapidly figured out the whole plan and arrested all criminals, successfully preventing the bomb from exploding. After the trial, Tyler was sent to lunatic asylum receiving psychological treatment. He was discharged from the hospital in 2012.”

Besides being cinematic vandalism, this authoritarian-coddling corporate censorship spits in the face of what Fight Club is: an anti-authority, anti-conformity primal scream of the underclass that slays American culture’s sacred cows. Tencent’s ending (which, according to Vice, was edited by the “copyright owner”) deflates the film into a whimper, ensuring law and order retain their rightful place as China’s dominant cultural hegemons.

When Fight Club was released in October 1999, it connected with me in a deep, lasting way. I was just out of high school, frustrated with everything and feeling utterly out of step with and disconnected from our consumption-driven economy. It could be too clever and lean too hard on the kind of simple philosophical posturing that seemed everywhere at the time, from Internet chat rooms to WTO protesters. But I loved the film then and love it still. I hadn’t seen it in years, but when I read Vice’s story I went back to Fight Club — partly in solidarity, but also because I had a feeling it would be particularly resonant in this age of pandemic and the Great Resignation. And, boy, is it ever.

Besides being a fantastic movie year, 1999 yielded a bumper crop of “work sucks” films, from Best Picture winner American Beauty (suburban dad-in-midlife-crisis Lester Burnham napalms his career by blackmailing his boss) to The Matrix (pre-Neo Thomas Anderson is a corporate nobody in some characterless cubicle farm), and Office Space (90 minutes of low-level tech workers plotting a way out of their dead-end jobs with the literal tagline “Work Sucks”). Fight Club is in that group, too, the Narrator’s malaise brought on by a soul-sucking routine of risk analysis for a compassionless auto manufacturer, reporting to a do-nothing paper-pushing middle manager, and filling his condo — in a building he describes as a “filing cabinet for widows and young professionals” — with junk from the latest Ikea catalog. The plot turns on his apartment exploding, which gets him living with Tyler; the destruction of all his worldly possessions putting him on a path, like Lester, to corporate extrication, albeit in a more hilariously bizarre (and bloody) way.

What set Fight Club apart from its peers, turned it into a cult classic, and makes it even more resonant today is its deeper prodding of the cultural currents driving the Narrator’s disaffection. Fight Club’s world is populated by overeducated workers wasting away in underskilled meaningless jobs for diminishing pay and vanishing respect. Welcome to America, right?. But the film pushes beyond the trope into an explicit critique of late-stage capitalism’s fetishizing gross inequity and working class punishment. White collar, blue collar, no collar — we’re all batteries powering wealth generation for an increasingly exclusive elite class. Our role is to work and consume, consume and work. Keep putting in the hours to get the paycheck to become “a slave to the Ikea nesting instinct” and don’t think too hard about what you’re doing or why or what it amounts to. You have a yin-yang coffee table! What else do you need?

“An entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables, slaves with white collars,” Tyler says at one point. “Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don’t need. We’re the middle children of history, man, with no purpose or place. We have no Great War, no Great Depression. Our Great War is a spiritual war; our Great Depression is our lives.”

Even then, that last bit was maudlin. But it resonated with certain viewers because it spoke a truth everyone else seemed unwilling or unable to acknowledge. The end of the Clinton ‘90s, with its overheated free-trade economy generating fabulous fortunes while gutting American industries and middle-class lives, felt like the ideal moment for a conversation about who has been left behind, and at what cost. Unfortunately it was smuggled into a film about dudes beating on each other before blowing up buildings, so it was lost on many filmgoers and critics. Watching it now, though, it feels more relevant. Consumerism is worse. Inequality is worse. Corporate power is worse. Prior to the pandemic, wages for most people have stagnated or declined. And the people who fill underclass jobs — those celebrated as “essential” and rewarded with poverty wages, no benefits, and unreliable schedules — are arguably more undervalued and invisible than they were in 1999.

At one point in Fight Club, a police commissioner vows to crack down on the underground group perpetrating Project Mayhem’s stunts, pranks, and crimes. Attending a banquet staffed by Tyler and his cronies, posing as waiters, he’s cornered in a bathroom, held down, and threatened with castration if he doesn’t call off his pursuit. “The people you are after are the people you depend on,” Tyler tells him. “We cook your meals. We haul your trash. We connect your calls. We drive your ambulances. We guard you while you sleep.”

Marginalized workers driven by nothing-left-to-lose rage are the force behind Fight Club’s fictional Project Mayhem. It’s an underground force in the film, as it was in real life two decades ago. But no longer. It went mainstream in 2020 and 2021 — how could it not? “Essential workers” were forced to risk their lives, not simply so other people could maintain some semblance of their lifestyles (the wealthy, yes, but also those who could work from home) but to protect the economy. Frontline healthcare workers created their own PPE. Retail employees acted as bouncers keeping the unmasked out of grocery stores. Delivery drivers, transit workers, line cooks, meatpacking laborers, anyone in the service industry — all on the economic front lines, all in immediate danger of infection and death. If they didn’t get sick, they knew people who fell ill. They saw friends and family die. And when the wave crested? They were thanked with angrier customers, more callous managers, and reduced pay checks as hazard bumps were phased out. American capitalism said the quiet part — what was given some cover in 1999 — out loud: You matter only as a tool for someone else’s prosperity.

Difficult to imagine going through that and not deciding enough is enough. “It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything,” Tyler says. It’s a message his acolytes embrace — and one that feels central to our ongoing, long-delayed Great Resignation moment.

Fight Club will never be for everyone. Good. Part of what makes it so potent is its total refusal of focus-grouped maximum appeal. It was a rough watch in 1999, its fight scenes intimately brutal, bordering on body horror; its language tough and uncompromising; and we’re never meant to sympathize with the Narrator or Tyler, nor are we expected to celebrate their cult or its increasingly anti-social terrorism. All of that remains true today — maybe more so, post-9/11. But its marrow-deep anarchy and existential angst has new urgency. Society has gotten worse, not better, especially for the kinds of characters at the center of the film, making Fight Club more relevant, not less — in both disconcerting and rousing ways.

It’s hard not to see the blind devotion, grievance, and increasingly destructive prankish violence of Tyler’s Space Monkeys in the perpetrators of the fascist January 6 insurrection. (We see a folder in Project Mayhem’s war room labeled “Disinformation.”) Similarly, it’s impossible to ignore that the agency and self-worth Tyler instills in fight club members has manifested in workers finally saying “Enough!” to a system that devalues them, their families, and their friends.

That central contradiction — between self-defeating violence and righteous self-actualization — is what makes Fight Club so challenging and alive. That tension only gets tauter as America becomes both increasingly aristocratic and nihilistic. It gives the film, already great, a kind of morbid timelessness. And it makes it necessary viewing — the real version, not the Tencent monstrosity — especially in this time of existential upheaval driven by Covid-19, nature’s own Project Mayhem.