The formerly Dutch village of Roode Hoek has come a long way since the 1600s. But on December 11, the motherland briefly returned to Brooklyn when Sander Dekker, the Netherlands’ Minister for Legal Protection, paid a visit to Red Hook, along with seven other officials from the Hague and a Dutch TV crew. Dekker, a politician from the center-right People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, occupies a position in his country’s government roughly equivalent to that of the United States Attorney General.

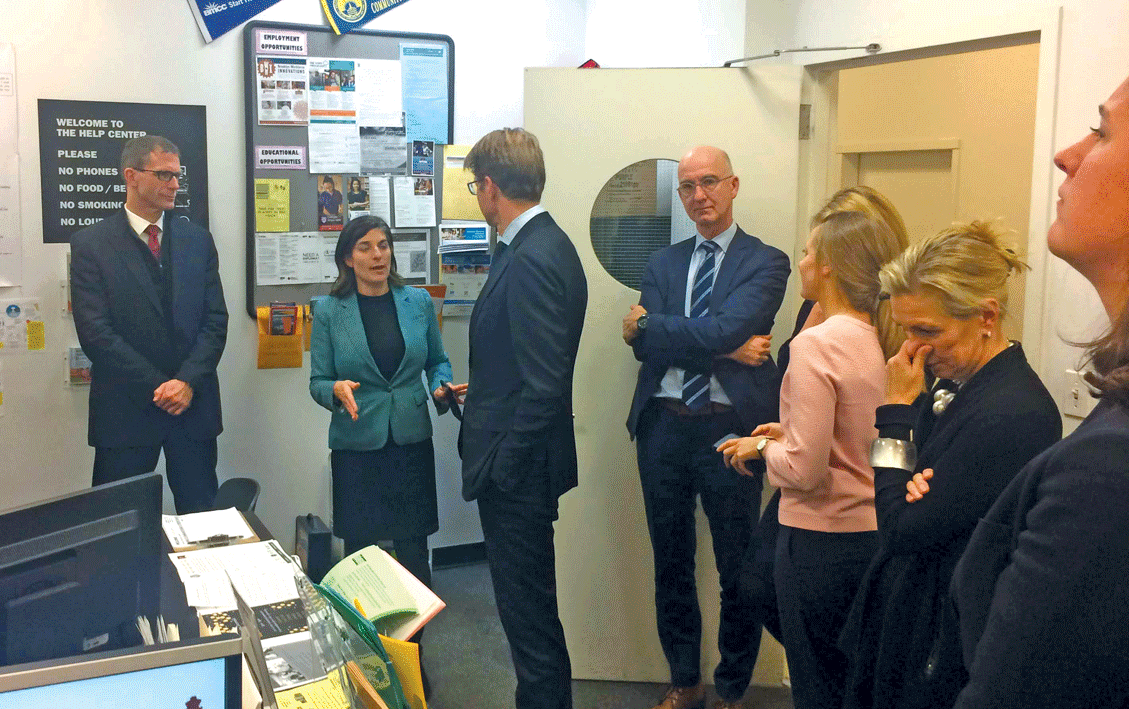

Plans to build a community courthouse in the city of Eindhoven — which will be the first of its kind in the Netherlands — prompted Dekker to take a tour of the Red Hook Community Justice Center (RHCJC), following an earlier stop at the Brownsville Community Justice Center. Both are projects by the Center for Court Innovation, a New York-based nonprofit that, through public policy research and consulting work, aims to advance the cause of justice reform and reduce incarceration. It works “in a very intimate way with government” in order to “nudge government to be its best self,” as the organization’s director, Greg Berman, put it.

The Center for Court Innovation operates in all five boroughs of New York City, Long Island, and New Jersey, but RHCJC is unique in that it combines criminal court, housing court, and family court into one experimental courtroom, presided over by a single judge. This synthesis allows for a holistic perspective that lends itself toward a problem-solving approach rather than a punitive one, pooling information to identify the underlying causes of troublesome behavior, such as unemployment, addiction, or inadequate housing.

RHCJC’s Alex Calabrese is an official judge of the New York State Unified Court System, hearing mostly misdemeanor cases from a catchment area that spans the NYPD’s 76th, 78th, and 72nd Precincts, but thanks to the Center for Court Innovation, the building at 88 Visitation Place also operates as a community center, providing social services like mental health counseling, job training, housing help, and GED classes. New Yorkers don’t need to get arrested in order to access these forms of assistance at RHCJC, but having them close at hand makes it easy for Calabrese — who may sentence offenders to drug rehabilitation or community service in some cases, using jail time as a last resort — to recommend many defendants to Court Innovation programs in lieu of punishment.

Meeting with the Dutch envoys, RHCJC project director Amanda Berman explained the idea of “‘procedural justice,’ where, if we create a process where people feel that they’ve been treated fairly, that they are being treated with respect, and they understand what’s going on and have a voice, that means they’ll be more likely to comply with the outcomes, and it means they’ll be more likely to trust the system as a whole.” RHCJC processes about 10,000 cases a year, but not all of them go to Calabrese’s bench.

Other methods of resolution include Peacemaking, which trains neighborhood residents to resolve disputes through conversation, and Youth Court, where teenage volunteers dispense binding sentences to low-level juvenile offenders who’ve already admitted guilt. These kids don’t have the authority to invoke fines or detention centers, but they can demand letters of apology or send their peers to skill-building workshops.

For the Dutch guests, Coleta Walker and Sabrina Carter of RHCJC summarized the practical and conceptual underpinnings of Peacemaking and Youth Court, which seek, at least in small part, to transfer the administration of justice away from a traditionally alienating bureaucracy and into the hands of the community. After listening to a 15-year-old describe his experience working in the court, Dekker gifted him a tin of stroopwafels, a specialty of Holland.

Amanda Berman also led the assembly into Calabrese’s courtroom, where the judge took care to empathize with repeat drug offenders (“It’s not easy staying clean during the holidays”) and called defendants to the bench to shake hands. Afterward, Dekker complimented the judge’s bedside manner: “It was wonderful to see the little chitchat after the formal case.” He speculated that, by establishing personal bonds with the defendants, Calabrese may have decreased their chance of recidivism because they “don’t want to disappoint” the judge.

As Berman showed the delegation around the building and pointed out the polite, user-friendly signage that RHCJC had installed, she emphasized “how you can use the physical environment to send a message” of comfort, warmth, and rectitude “to everyone walking through the doors.” According to Berman, the challenge of an enterprise like RHCJC is to transform a courthouse — a destination typically avoided at all costs — into a place that people “want to be in.”

Peter Slort, the Counselor for Justice and Security at the Netherlands’ embassy in Washington, D.C., accompanied Dekker on the tour. He called the experience “very fruitful. In the Netherlands, we are experimenting with ways to innovate the court system. The goals are to bring the court system closer to the people and to make it more effective. We were impressed by the results of the Red Hook Community Justice Center, and learned a lot.”

Dekker and Slort weren’t RHCJC’s first international guests. Berman, who noted that observers come “on a regular basis,” recalled previous visits from Japan, New Zealand and Israel. In addition to its “hyperlocal role in working with the community here,” the Justice Center intends to function as a “laboratory to test out new ideas and to serve as a model for other jurisdictions,” she said. “At the end of the day, our hope is that justice reform will spread far and wide.”