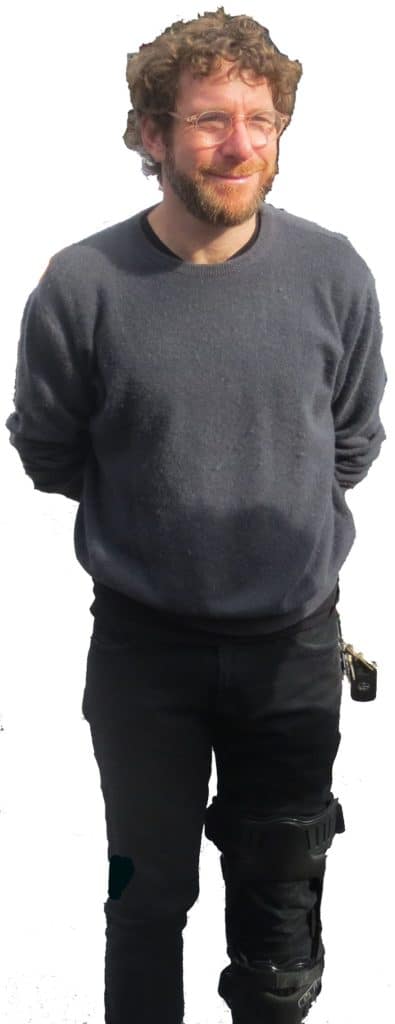

The following is an interview with artist Dustin Yellin, founder of Pioneer Works.

RHSR: What’s the genesis of your work?

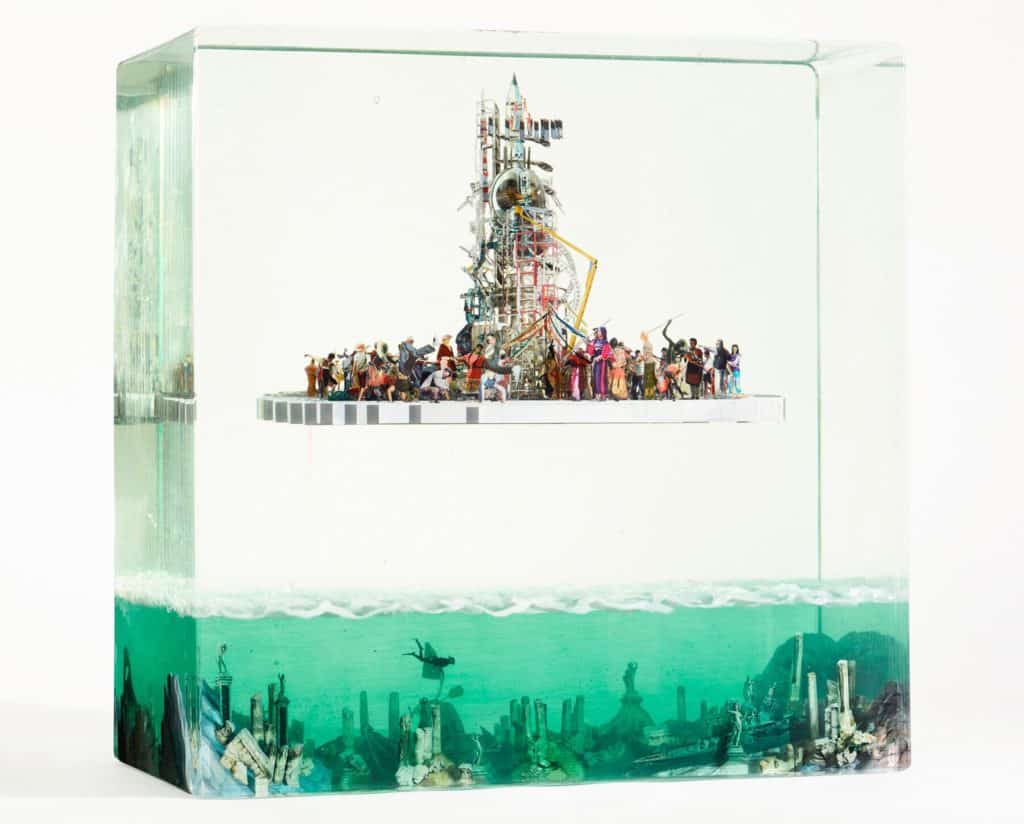

Yellin: The works in this building are of the three hands: the Descriptive, the Prescriptive, and the Impossible. The Descriptive being how do you use different mediums to tell stories, narrative stories, and that’s what you see happening in the Politics of Eternity and in the psychogeographies and the different bodies that are inhabiting this building. Pioneer Works is an institution and a social project as a Prescriptive measure to use culture and science as part of culture to bring people together to create systemic change and to rethink systems. And then the Impossible, which is a project I’m working on called The Bridge, which is to build a monument to the end of fossil fuels but with a supertanker on its nose.

So that’s kind of the practice right now. But at this point I think very much about Joseph Beuys and I think about civilization as a sculpture and I think about civilization as a hallucination and I think about how all that we experience and all that we know is inventive and is just some sort of perceptual reality.

RHSR: Okay. So when did you start doing art?

Yellin: As a kid. I was inspired by nature and by assemblage. Stacking rocks and sticks, and more again of perception, of seeing my external world, geology, as art, seeing everything as art in my teens. And then I got obsessed with science and I also got obsessed with climate, very much obsessed with this idea that our species was headed down a trajectory that was seemingly untenable, which seems to be very much the zeitgeist right now and the picture we have created for ourselves. My end vision is Neverending.

RHSR: What did bring you to Red Hook? You used to have a place up on Imlay and I lived on Van Brunt.

Yellin: I came to Red Hook with a mentor of mine, Tony. Year 2000, I think, was the first time, and I loved it but then didn’t come back for a few years later. But I always was captivated by its relationship to the water. I just love the water and I was always crazy about it with a sort of small-town feel, almost like an old Western, the one-lane town and very much not a big city.

RHSR: Well, who were your influences?

Yellin: Nikola Tesla, Buckminster Fuller. I mean really early on but over the years, you know, Joseph Cornell, a lot of my friends, younger artists. Werner Herzog, Pablo Neruda, Rilke and Frank O’Hara, Emily Dickinson. So really across different mediums. It wasn’t just this small group of artists or the specific idea around art, but really many, many, many different people, and nature.

RHSR: How did your upbringing introduce you to these people?

Yellin: I was very much a late bloomer. My parents were amazing, but I wasn’t very cultured. In my late teens I met a physicist. He really was one of the first people to point to a bunch of cultural lighthouses that kind of turned me on. And then coming to New York City at 19 I again met a bunch of other people and I really learned from my friends and the people around me.

I got to make it as an artist and if I make it as an artist I’m going to get a voice and if I get a voice I’m going to build a table and at the table I’m going to put the greatest scientists in the world and I’m going to put the greatest philanthropists and the greatest thinkers and they’re all going to work together to build a better world. So it was a very, very idealistic, utopic, and ambitious sort of dreamlike state at 19.

RHSR: Where did you first live at 19?

Yellin: In 1994 I rented a little tiny room on Crosby Street.

Yellin: Well, I used part of the apartment to work, then I got another studio with friends in Chelsea. This is way back before Chelsea was Chelsea.

RHSR: What kind of work were you doing?

Yellin: Crazy, weird paintings and drawings and collages. Rauschenberg and Schwitters were influential.

RHSR: So you had this vision or this idea you wanted to build. Did you have this big idea at the beginning?

Yellin: Pioneer Works, you mean?

RHSR: Yes. For building a platform of all these philosophers and –

Yellin: Yeah. There was definitely the germination and even a document in like ’97 or ’96, early on.

RHSR: Something you wrote.

Yellin: Yeah. And I wrote it with a friend of mine who’s no longer here. We were in our early 20s.

RHSR: You laid a blueprint out and how has it developed since Crosby Street to Chelsea?

Yellin: It evolved.

RHSR: How did it do that?

Yellin: Super organically, super naturally, and super – I think by the time it was coming to life in the current form I had tilled the soil with lots of relationships and there were so many people at the meta-table, if you will, to help build it with me. Gabriel, the artistic drafter, Gabriel Florenz, and Matthew Putman, early board members, Janna Levin, who runs our science program. More and more people just showed up at the table.

RHSR: What attracted them, do you think?

Yellin: I think everybody wants to build the world they want to live in.

RHSR: How was the world you grew up in? I mean as a kid. How were your family relationships? Move around a lot? Pretty stable?

Yellin: Moved around. My father and mother divorced when I was five, different states, kind of went shepherding between them but a very loving family, not too traumatic, you know. My father is a very modest man.

RHSR: When I first sort of came across you showing your book, I thought there’s a lot of hallucinogenic vision being presented idea-wise. I guess I’m asking how did they influence you, give you vision?

Yellin: Yeah, I had many, many, many visions. I think it’s really great that all these different avenues for opening up the mind and for dealing with different ailments and different approaches are being embraced more now. Perhaps they were 40, 50 years ago and now again.

RHSR: How do you think that influenced your work?

Yellin: Greatly.

RHSR: How so?

Yellin: I think it helped, you know, as Huxley said, open the doors of perception and potentially shift the lens in which I experience the world. So, you know, I think everybody has their own road to walk down. When I was young I was exposed to these things and I think they really helped shift my consciousness and my ideas and also potentially give me an elevated sense of what was possible, maybe even to the point of delusions of grandeur but then those delusions of grandeur potentially didn’t manifest.

Yellin: I think it helped, you know, as Huxley said, open the doors of perception and potentially shift the lens in which I experience the world. So, you know, I think everybody has their own road to walk down. When I was young I was exposed to these things and I think they really helped shift my consciousness and my ideas and also potentially give me an elevated sense of what was possible, maybe even to the point of delusions of grandeur but then those delusions of grandeur potentially didn’t manifest.

RHSR: You are manifesting them. Right? That takes work.

Yellin: It’s taken 25 years of solid work and even now I work pretty much seven days a week and am always working and it’s very intense. I haven’t had a family. I haven’t done much else but work.

RHSR: How old are you?

Yellin: 44.

I think of my sculpture almost as frozen movies. My process is extraordinarily slow. So even though it feels like a pretty big studio and there’s a bunch of people working, that piece took two years.

RHSR: It’s pretty involving.

Yellin: So you can imagine, in three months, not much happens because it’s so slow. But I’m in my mind a lot, like a lot of the work I do is ideation, you know. I’m thinking about what is going to be the narrative in the next work or how do I knit together five previous works. What is the work saying about climate, which is something I’m thinking about a lot right now. Have you read The Uninhabitable Earth yet? You should read that book. It’s a neat book. Oh, there is one tonight, too. Gary Marcus on “Minds and Machines.”

RHSR: So how do you meet all these people?

Yellin: Well, I mean, we have a programming team. I meet them when they show up. I mean, specific to science, that’s Janna Levin.

RHSR: People go out and make contact.

Yellin: Well, Janna, our director of science. She’s an incredible – Janna Levin, an astrophysicist. She’s our director of science. She’s tenured up at Columbia.

RHSR: What are you’re thinking of, how it’s going to tie with other things, and –

Yellin: I’m thinking right now. I think a lot about the state of our species. What is the state of our species with numerous very connected existential threats and specifically around warming. So how does warming affect migration? You know, where does fresh water play into that? Where do fossil fuels play into that? Where does capitalism play into that? Where does disease play into that? What does it look like if parts of the earth are uninhabitable because of warming? What does it look like when many, many, many cities that we live in now are not livable in a hundred years? What does a hundred years look like? How does that affect our species? What does it look like with artificial intelligence and machine learning?

What does it look like for modalities of meaning making if we go from an economy of scarcity to an economy of excess? Should there be a universal basic income? Should there not? How would that work? Do we need to build new systems to govern? What is tribalism versus globalism? These are the things I’m thinking about.

RHSR: Did you ever read McLuhan?

Yellin: Yeah.

RHSR: He talks about these ideas in a very perceptive way. So that’s an awful big table that you’re thinking about. So how is it going to tie into your workday today? What are you going actually do today?

Yellin: Today. Look, I’m meeting with a lot of people today. Everything ties into everything.

RHSR: You have a staff that helps you?

Yellin: A couple of them, yeah. One at Pioneer Works and one here.

RHSR: How does Pioneer Works factor into your artwork? Is it like a stage almost?

Yellin: No. As you probably know, I don’t show these art works at Pioneer Works. So Pioneer Works in itself is a work and my obsolescence is my success in the work of Pioneer Works. My obsolescence is its success. If Pioneer Works can thrive without me, then that work is a good work.

RHSR: So how’s it going?

Yellin: It’s getting better and better. Lots to do, still.

RHSR: So how’s it going to get better today? What little increments might take place today?

Yellin: You know, I don’t know because I haven’t looked at the calendar yet. Every little tweak and turn of the knob, meeting with someone, a thousand people showing up today for a science talk. You know what I mean? We have a board meeting tomorrow. There’s always stuff happening.

RHSR: It’s like recording you and your progress.

Yellin: Not me. Other people.

RHSR: Other people.

Yellin: Not me. Other people. Pioneer Works is its own thing. This is my baby but Pioneer Works isn’t about me. Pioneer Works is about rethinking how cultural production and learning and reimagining the commons and building community and access and all these things happen inside of a city.

RHSR: And Pioneer Works is like a micro city within a bigger city?

Yellin: No, not a micro city. No, I’m just saying rethinking the commons. What in the 21st century is a community center? What in the 21st century is a school or a museum? How do we bring scientists and artists and engineers and architects and filmmakers and writers to think together? How do we get away from the elitism of the market and give access to all these things? How do we make science part of culture and not in a vacuum behind closed doors in academia?

RHSR: Do you have a spiritual aspect to Pioneer Works?

Yellin: A spiritual aspect?

RHSR: Scientific and spiritualism.

Yellin: For me, they’re all the same. I really believe they’re the same. I don’t separate these things.

RHSR: Well, give me an example of what a school is today and your idea? What’s your idea of a school?

Yellin: Pioneer Works. I mean that’s my idea. How do you bring in people to teach, bring in people to work, make sure the public can come in and get access to it? How do you break down these silos and how do you breed critical thinking by getting people to learn from each other and exchange ideas?

RHSR: You’ve been successful with that. I guess I’m digging a little bit. How does that happen?

Yellin: Well, I mean I don’t know how it happens. It happens over time, lots and lots of time, and people. People are the key. If you put incredible people together incredible things happen.

RHSR: How do you get incredible people to come together?

Yellin: I think there’s a sense of gravity.

RHSR: Well, the gravity as far as I can is this is a pretty substantial group right here. Like Jupiter has a bigger gravitational field than earth, more things are attracted to it. And I think that’s going on here for you. You’ve created a pretty gravitational field for other people to come to.

Yellin: Right. And I think those things inform themselves. Tonight a thousand people will show up. They’re not showing up for me. They’re showing up for these incredible scientists and those incredible scientists are then attracting other people that attracting other people. Gravity begets gravity. Right?

RHSR: It’s like word of mouth. They come to a nucleus and they exchange and they may go out and exchange further.

RHSR: It’s like word of mouth. They come to a nucleus and they exchange and they may go out and exchange further.

Yellin: And then that attracts more. Yeah.

RHSR: Yeah. So we’ll see how mine goes. I don’t think it’s going to go as well as yours is.

Yellin: But I don’t even think of this as mine anymore. I try not to. I really think of it as its own solar system and I’m part of it.

RHSR: And a corporation is a legal entity anyway. Right? Well, let’s just say a gravitational field. Right?

Yellin: I’m all about a gravitational field.

RHSR: Well, you’ve been successful at that. Who have been some of the artists and speakers that have mostly influenced Pioneer Works?

Yellin: It’s such a long list. I wouldn’t even know where to start. Like I said Gabriel and Janna and the leadership teams who work at Pioneer Works and helped build it. But the board of directors who help support it. You know what I mean? All the incredible residents and artists and writers and musicians and thinkers who have been part of its genesis. Yeah, everyone.

RHSR: Is there anything you’d like to say in relation to this interview in the local newspaper?Wwhat would you hope would be expressed in it?

Yellin: I hope that Red Hook, it’s such a small village, that I hope everyone in Red Hook can come together more and communicate more to try to build the village that we all want to live in. So I would say Red Hook has a great opportunity in its scale to really together envision what it wants to be the next decade.

So far it hasn’t changed that much. I mean it’s changed. We don’t have big tall glass buildings which is great and I hope we stay low, so to speak.

RHSR: You’re on a landfill.

Yellin: Yeah. I hope that the city spends more time revitalizing the bulkheads and fixing them up. I think Van Brunt has a few more places to eat but it doesn’t really compare to other parts of, you know, to Williamsburg, or the city. Do you know what I mean? It’s still relatively slow, which I like.

RHSR: Yes but we are on a flood plain. I’m not sure what the city thinks about Red Hook. It’s a floodplain. Are they doing anything to protect you? They’re doing stuff in the Rockaways.

Yellin: I have to find out.

RHSR: That would be a great project.

Yellin: Well, we’re talking about some stuff like that.

RHSR: Okay. Well, I hope you hear about it. I’ve seen the city presentation.

Yellin: Yeah, morphing. But it’s not just Red Hook. It’s Lower Manhattan. It’s Miami. It’s Los Angeles, Jakarta. It’s global in the sense that the oceans are coming for us.

RHSR: I’m a local guy who writes for a local newspaper so I really just want to emphasize…

Yellin: Red Hook.

RHSR: Yeah. The paper’s not going to get read outside this neighborhood. Some might. So what is the city planning? Are they abandoning it because it’s a floodplain?

Yellin: I think they probably want to bolster up. I would think they want to bolster up the coast a bit to try prevent water from coming in.

RHSR: I mean Red Hook is Red Hook, local people, not Jakarta or Paris or even New York City. It is part of New York City. So I’ll keep on trying to find out what’s going on. Thanks.

Yellin: It’s a pleasure.