When Deborah Ugoretz first came to Red Hook, in the year 2000, the neighborhood and its artists charmed her immediately. “I was just inspired by this whole environment,” she says. “This neighborhood exudes creativity and production.” It took some time, but Ugoretz eventually moved her own studio here in 2011 and has become a huge booster of Red Hook’s artist community. She co-organizes Red Hook Open Studios; the yearly event where local artists open their doors to the public. We talked to Ugoretz about the community she loves, and about her own work, which often takes inspiration from Jewish spirituality.

When did you first start making art? Were you an artistic kid?

I always drew as a kid. In fact, I had this dream when I was about 11 years old – it happened three days in a row. So, the first night, I have a little slit in my cheek. The second night, the slit is beginning to open. And the third night, I’ve got a third eye there. And I always felt like, first of all, it was really freaky for an 11 year-old to have a dream like that.

I was just going to say. Did you even have any idea how to process that image at age eleven?

It totally freaked me out. I don’t know. I just felt like I had a different way of seeing the world from my relatives, my cousins who I grew up with. And I always liked to observe the world. I was addicted to watching variety shows on TV, and I would create my own variety shows by drawing them. I had a very visual sense of the world.

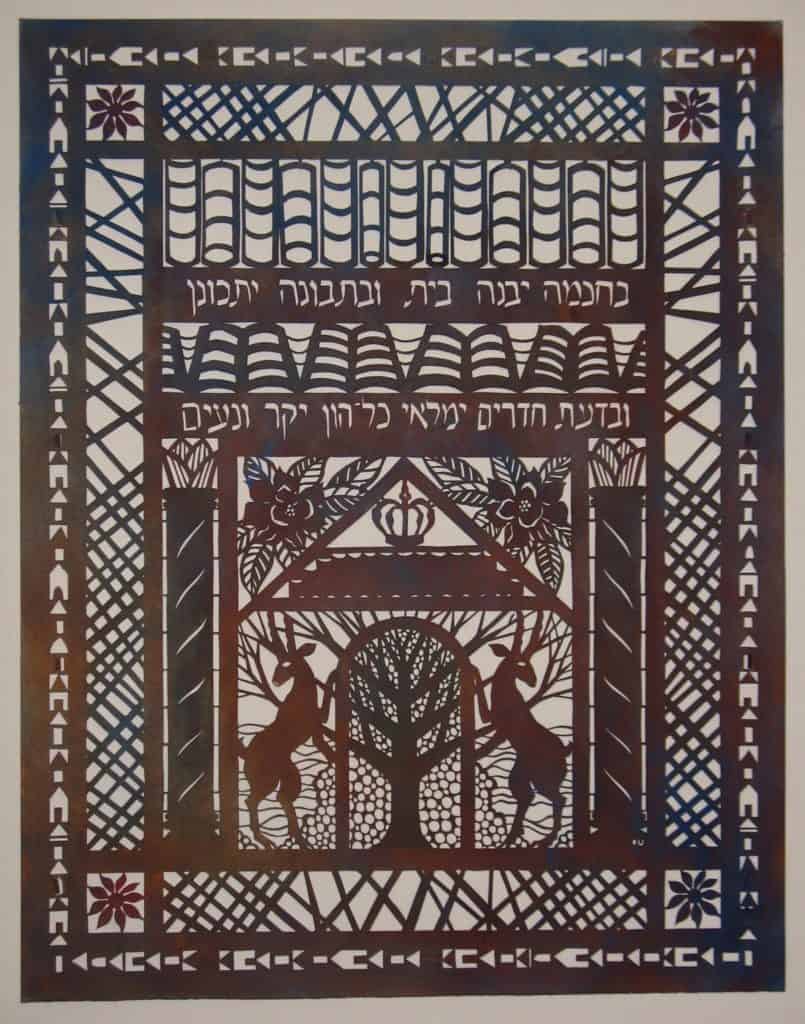

You work in a lot of different media, but I want to talk about these works you make out of cut paper – they’re almost like woodcuts or prints.

I first saw works like that either in Israel when I was 18, or in the Jewish Museum—they’re part of a Jewish tradition of paper cutting. When I saw them, I was really intrigued by the idea of just taking a piece of paper and cutting and creating negative and positive space. I thought it was a very interesting problem to deal with. How to have the sense of balance.

It’s a kabbalistic idea actually, called tzimtzum. It’s the idea that God builds his presence in these vessels and they exploded with his energy and created these voids, between these shards floating around in the universe. And the emptiness is sort of the space that has to be filled in with meaning.

On that subject, there are a lot of concepts from Jewish thought and philosophy that crop up in your work. What was your relationship with Judaism like growing up?

it was certainly multifaceted. I mean, grew up as a pretty observant Jew, I guess you’d call us “conservadox.” Which means, conservative synagogue but keeping kosher, not working on the Sabbath. And also growing up in this youth movement, where you’re really kind of taught to have this unquestioning love for Israel.

But then there were always the challenges of wanting to be like everybody else. In public school, we celebrated Easter, we celebrated Christmas. And they would sort of do a little nod to Hanukkah by singing some stupid lame song. It was this sort of conflict of loving who I was, but also wanting to be a part of American Christian society.

Before I discovered the paper cutting, I really didn’t have a sense of the potential within Judaism to create art. I saw these paper cuts, and they were full of imagery of animals and flowers, and it opened my eyes. So, I started looking in text for visual imagery and found tons of visual imagery within prayers and the Bible and rabbinic thought and language.

Do you believe in the Jewish God now, as an adult?

Eh, we have a difficult relationship. I don’t think I believe in God, but I believe in something. Some kind of inspirational force.

It’s interesting. I don’t do the work to praise God or glorify God. At all. It’s more like a way of communicating the wisdom within the teaching. There are like these gems that are still relevant today. Of keeping up hope and finding beauty in the world.

You’re one of the lead organizers of Red Hook Open Studios. Is it inspiring to get to see all the work your fellow Red Hook artists are doing?

It’s been great. I really love doing it. I love meeting everyone. I get really inspired and energized. It’s building community, as much as you can with artists who are a little bit buried in their work [laughs]. They’re very focused, but they do also need community.

One Comment

Pingback: Ugoretz Art