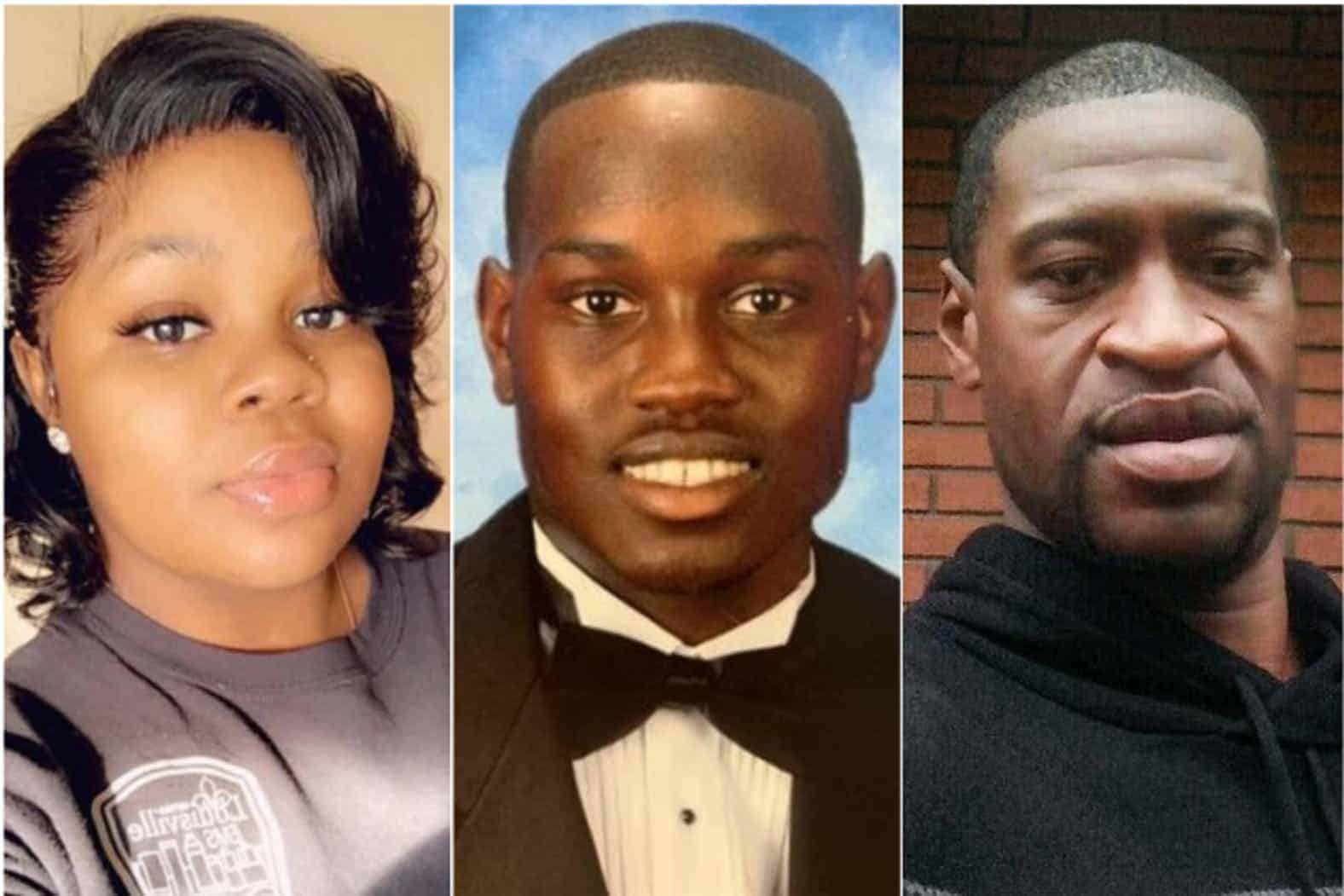

In a word, fatigue may be the most accurate response to 2020 thus far. Pandemic aside, viral content of Black people being racially profiled and murdered by either vigilantes or police is sadly routine. On March 13, 26-year-old EMT Breonna Taylor, was killed by a spray of bullets from officers shooting under a ‘no-knock’ warrant – it appears the officers may have raided the wrong home. On February 23, 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery was followed, shot, and killed by three men while he jogged through his neighborhood. The three men, William Bryan, Travis McMichael, and father Gregory McMichael, believed Ahmaud Arbery to be ‘suspicious’. On May 25, George Floyd died as a Minneapolis officer knelt on his neck for several minutes. Floyd’s body went limp on camera. Officers believe Floyd may have used a counterfeit $20 bill at a deli.

Floyd cried, “I can’t breathe, they gon’ kill me,” chilling last words echoing the equally horrifying death of Eric Garner, who also died via police induced asphyxiation in 2014.

The recent killings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery have reignited familiar outpourings of marches, riots, and hashtags. Public outrage around incidents like these typically rises and settles with little to no long-term corrective action. Here are my thoughts.

Often, conversations around racial injustice in America bestow responsibility on Black people to make others understand our plight, and to somehow transform or correct white supremacy. This belief is rooted in the systemic and sociological belief that Black people are inherently guilty of “something” and thus need to prove our innocence.

On any occasion, live Black bodies can be reduced to bullet casings, whether bird-watching or jogging. As a result, Black people like myself grow up trying our best to rub the targets off our bodies, with limited and inconsistent individual success. The first and only Black and biracial man to be president of the United States had to be a model of near perfection, whose indiscretions included wearing tan suits and smoking cigarettes. Respectability may give access, but it won’t grant immunity, and it damn sure won’t even the odds.

There is no great chasm between the snuffing out of Black bodies that occurred at the dawn of the last century and now. Technology and laws may have changed, but our ideas and practices around race and “worthiness” haven’t. Minneapolis officer Derek Chauvin knelt into George Floyd’s neck and killed him on camera because this society tells him he can. Former Franklin Templeton employee Amy Cooper, called the NYPD while falsely accusing writer Christian Cooper of threatening her life because she knew she could. Time is the only divide between Amy Cooper and Emmett Till’s accuser Carolyn Bryant.

In contrast, Black people don’t have the social power as a community to take any of the aforementioned actions. Yet we do need social power. Black people need enough social power to render ‘Amy Coopers’ and violent officers less likely to harm Black bodies. If centuries of brutal racial injustice have led to Black people experiencing psychological and physical trauma, what has it done to white folks? What has being told for centuries, explicitly and implicitly, that you are superior done to the empathy and humanity of white America?

Moreover, collective social power won’t come with any adherence to America’s hypercapitalist structure. There aren’t enough Black millionaires, and celebrities to fix systemic racism and violence. Hypercapitalism won’t save any Black person, Black people need collective wealth and a collective movement that pivots away from capitalism.

Every generation had specific goals, desegregation in the 1950s, or voters’ rights in the 1960s. If nothing else, the most immediate fight for this current generation might be police brutality. While body cams and surveillance don’t prevent the killings of Black people, what they do provide is objective data and information that can be observed. (Currently, there is no federal requirement for officers to use body cams.)

Americans look at the civil rights era as antiquity, lost in black and white archival footage. What the recording of these police killings proves is just how close to the civil rights era we actually are. Anyone who watches interviews of civil rights leaders like Bayard Rustin or Coretta Scott King would find that most past concerns have not changed for Black Americans today. Simply put, the dream has not been realized yet.

In a 1979 interview, activist Bayard Rustin said, “The success of the civil rights era was attributed to three things, achieving the right to vote, the right to use public accommodations, and the right to send your child to a school of your choice. It did not address the economic and social problems of Black people. The first lesson is, don’t try to repeat what was done before you, because we are in a different period. The movement wasn’t just leaders, and a few politicians, it was everyone. Don’t vote with your feet and rhetoric: protest is no substitute for the ballot box.”

Roderick Thomas is an NYC-based writer and filmmaker and the host of Hippie By Accident podcast (Instagram: @Hippiebyaccident; email: rtroderick.thomas@gmail.com; website: roderickthomas.net).