I just got a blast message from Governor Cuomo advising New Yorkers: “When you get a call from NYS Contact Tracing – Answer your phone! Any information you give a COVID contact tracer will be strictly confidential and treated as a private medical record.” Wow! If only I had a Governor paving the way for my phone calls when I did contact tracing many moons ago…

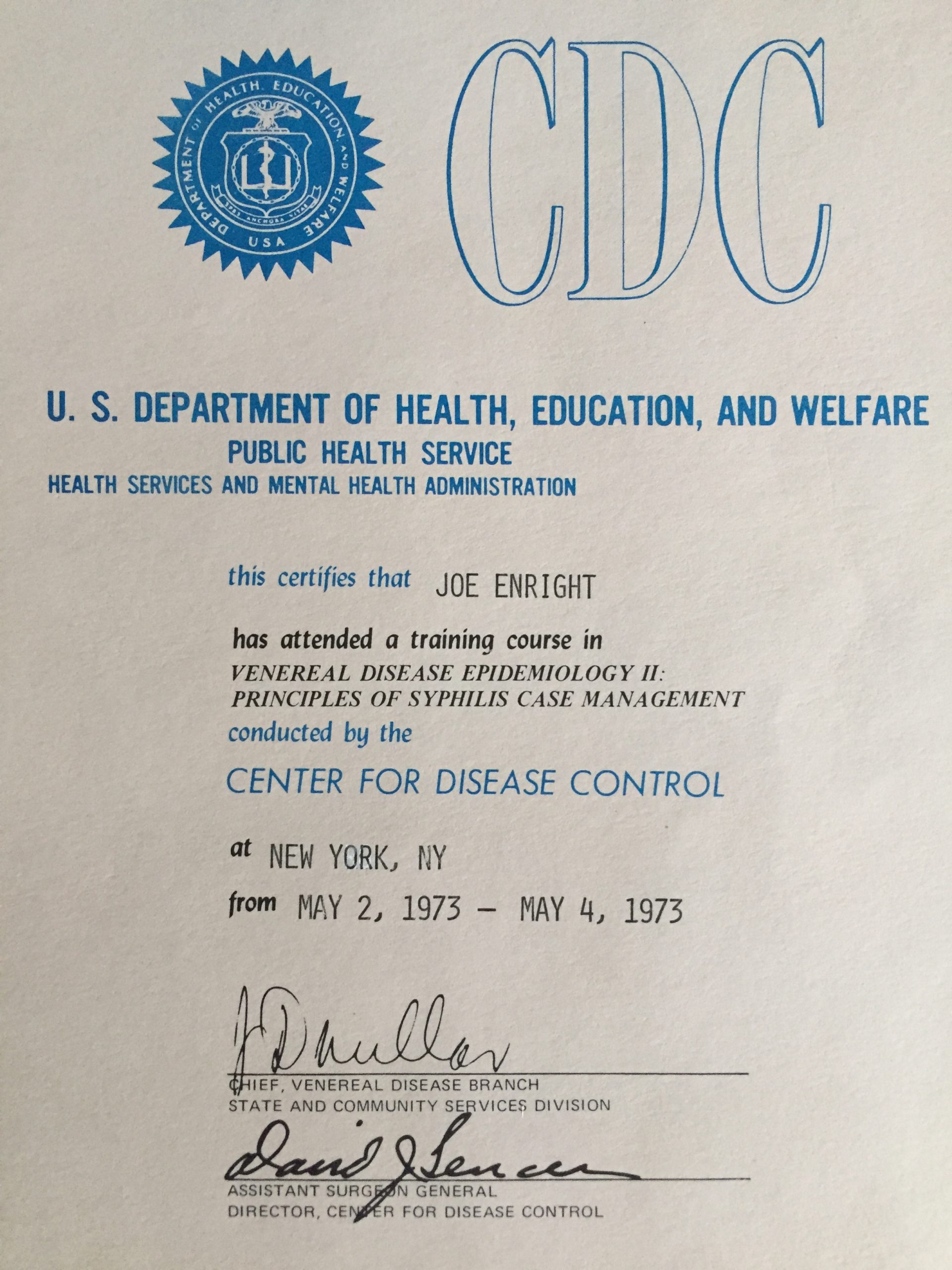

At the time I had no idea syphilis was spiking in New York. Or that the Tuskegee scandal had just broken. Then again I was oblivious to a lot of things in 1972. But I was happy to have a job as a Public Health Advisor for the Center for Disease Control. That much I knew.

It was a rocky road that led me to epidemiology. In September 1969 I passed my Selective Service pre-induction physical. Then the draft was miraculously suspended in favor of a lottery tied to birthdates. But I drew number 6 with a bullet – a sure-fire call-up a month thence. Naturally, I quit my Wall Street back-office job in order to party non-stop before Uncle Sam’s “Greetings” arrived. After the Top 40 numbers passed me by, I went down to the draft board and was chastised for not knowing when I was born “despite your fancy schmancy education!” The bogus birthdate they had on record was bubbling under their Hot 300.

What? I’d never be drafted! I’d never write the great Vietnam War novel! Or get sent home in a body bag. Or, much more likely, get shipped to Alaska to eavesdrop on Ivan as payback for surviving three years of Russian language courses. So after sobering up, I dropped into a backpack my good luck charm – a .22 caliber slug recently taken out of my left ear, the remnant of a drive-by shooting on Bedford Avenue – and lit out for the territories. Bye-bye, drive-bys. Hello, Greyhound!

After a series of inglorious non-Kerouacian adventures I wound up in a furnished room with a Murphy bed on Northwest Lovejoy Street in Portland, Oregon. Driving a hack paid the rent. Waiting by the bus station one night, fantasizing about a fare who might need a ride to Salem, I reviewed my life out West. Aside from seeing a lot of Sam Peckinpah movies which were always playing somewhere, I mostly watched the city sidewalks get rolled up by 10PM. Deadsville, daddy-o.

I headed back to Brooklyn and almost immediately saw a want ad for some sort of government position “advising patients.” Just needed college and a driver’s license. I figured they wanted someone of average intelligence to drive sick people. OK, I’m game. In a Foley Square office, the interviewer seemed more interested in my Portland cab job than college, which seemed odd. More on that later…

The New York rise in syphilis had been quickly detected by the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, which concatenated contagions in boring charts they distributed via their less-than-sizzling newsletter, The Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Review, so flimsy it seemed to be printed on toilet paper. The issue in my orientation package headlined a slight uptick in the Bubonic Plague in New Mexico. On the subway to my assigned post in Harlem, after making a mental note to refuse any transfer to the southwest, I wondered why the CDC was in Atlanta.

Turns out, as World War II descended, the Defense Department realized all the new training camps down South were malaria breeding grounds. Disease Fighters, Assemble! Washington DC had run out of office space, so Atlanta was chosen as their home for the same reason Sherman destroyed it: it’s a hub. After spraying boatloads of carcinogenic DDT, the “Malaria Control in War Areas” then morphed into the “Communicable Disease Center” in 1946. In the 1950s the Center relocated from office space on Peachtree Street to a large complex astride Emory University just before the US Public Health Service placed under its command an army of do-gooders it dubbed PHAs – Public Health Advisors.

The PHAs were then winning the war against another foe that challenged our GIs: syphilis. The prevalence of this bacteria, spread only via sex, indicated that many men in uniform had not been paying close attention to the training films warning against frequenting “floozies.” Nonetheless the suppression of syphilis in the 15 years after World War II was one of the great success stories in the history of epidemiology. And that history was now being threatened by a revival of venereal disease in New York and other sin cities at the dawn of the sexual revolution. Yikes!

The day I started getting paid to combat syphilis, a PHA leaked to the press the existence of the ongoing Tuskegee Study. Since 1932 the Public Health Service had been recruiting poor Alabama black men – under the pretense of offering free medical/burial care – into a study of “blood disorders.” In fact its only purpose was to follow the effects of untreated syphilis among African-Americans. Even after the 1947 introduction of penicillin as the first effective treatment, it was never administered to the participants. Contagion, congenital syphilis, and death followed.

It was against this backdrop that I walked into the “Social Disease Clinic” in a run-down office building on West 125th Street, a block east of the Apollo Theatre. After being introduced to the nurses, doctors and lab techs, I was told to draw blood from a line of patients stretching the length of the waiting room. A kindly doctor showed me how to do it by taking blood in slow motion from a couple of apprehensive young women.

“OK, you’re up,” he announced and departed.

My first victim was a portly middle-aged truck driver. He seemed to sense my anxiety.

“Don’t worry, son,” he smiled. “If I survived one of Patton’s tank battalions, I can survive you.”

He did. As did many others as the months rolled by. After drawing blood, I would wait for the diagnosis and treatment and interview the “positives” to get names and locating information for their sexual contacts. Then came the hard part: I had to find those contacts. Many had no surnames, and even fewer had phone numbers. But I did have an aptly-named two-door Gremlin to flit around the places they frequented, trying to convince them to come into the clinic or, failing that, to draw a field blood specimen.

A few weeks after starting I received some formal training on interview techniques along with two dozen other rookies at another Social Disease clinic in Chelsea. The CDC stressed empathy and confidentiality. However, in a stunning “do as I say, not as I do” betrayal of privacy, the trainers placed a hidden microphone and camera in the interview room so we could all watch each other try our hand at “confidentially eliciting sexual contact information from the patients.” Well, unlike Tuskegee, at least these folks got treated: an injection of 2.4 million units of bicillin in each buttock.

We were told to study the patient’s chart before we entered the room, keying on some fact in their background that we might use to build rapport, no matter how tenuous, and to begin the interview by cheerfully stating, “You know, we have a lot in common.” But as I studied the scribbled notes of nurses and doctors who had poked and prodded the 40-something handyman

now sitting across the desk from me, I drew a blank. He had just been treated for syphilis and gonorrhea, probably had hepatitis, was actively mainlining heroin and apparently was on parole for rape.

“You know, we have something in common,” I offered, scanning and rescanning the chart, looking for something, anything…

“Yeah? Like what?” the frail-looking Patient X countered, unconvinced, half-sitting to rub his buttocks.

As the seconds ticked by, I knew I had to say something. “Well, sir, from what I can see on this chart, we are both inhabitants of the planet Earth.”

And with that, the class on the other side of a thin plasterboard wall exploded with laughter.

“What’s that?” Patient X asked, looking at the wall suspiciously, leaning forward.

“Oh, that’s nothing,” I said. “There’s a training class going on in the next room. So let’s get back to our rapport-building exercise…”

More laughter.

“What’s goin’ on in there!”

“Must be a funny class, right? Listen, sir, we need to get everybody you’ve had sex with for the past two months into the clinic for treatment.”

“Why?”

“Because they’ll get sick if we don’t and infect others too. Just like you were infected.”

“No need. I got it from Betty the other night, that barmaid skank at Andre’s Tavern.”

“Well, sir, she might have given you gonorrhea, but not syphilis. That takes a month. Who were you having sex with before the barmaid?”

“The Super in my building. He’ll have sex with anything that moves.”

Laughter rings out beyond the wall. Patient X scrunches his eyes but continues. “You can’t tell him I told you, though.”

“Of course not. We never say who told us. Anybody else?”

“Well, Cassandra of course.”

“Who’s she?”

“My niece. She’s full-grown now.”

“All right then. Aside from the barmaid, the Super, and your niece, anyone else?”

“No.”

“Are you sure? How about the garbage men?”

More laughter. Louder than ever.

Antsy to begin with, Patient X was now out of his seat and on the move…A few steps down the hall, the door kept open to allow some ventilation on a sweltering day, he saw the class staring at a closed circuit TV screen displaying me in profile, shaking my head, wondering if I still had a job.

Over the course of the next two years as Tuskegee gradually gave way to Watergate, I deep-sixed the sarcasm and became a good interviewer. And an even better tracer of lost persons. My secret? I befriended a lot of local bartenders who passed on my scrupulously confidential notes. I also ventured into some half-vacant tenements with a tire iron up my sleeve and got rousted coming out by cops who thought I was a drug dealer. I also filled blood vials in locations that were far from hygienic.

Two decades later at a fancy party, I met a much older gentleman who said he once worked for the CDC. After the second cocktail he told me he was the executive who oversaw the 1972-1973 campaign against the syphilis spike in New York. During the third cocktail, he asked me if I was a cab driver.

“No. You want me to call you one?”

“I mean were you ever a cab driver?”

“No…Well, except for a brief time out in Portland during my alienated youth in search of America episode when…”

“Was that before you became a PHA?” he interrupted.

“Yeah, right before that.”

“Well, that’s why you got hired. You see, we’d been suffering remarkably high attrition among traditional recruits seeking a career in public health. So we shifted gears and started looking for street-smart applicants who could gab – college-educated hacks like you.”

He said the strategy was a great success. Syphilis had been suppressed again. Despite Tuskegee. By ex-cabbies. And with no help from a Governor.