In late December 2019, the east side of Conover Street between Coffey & Dikeman Streets was sold to the Diamond Development Group (the exception is a 20-foot wide strip at the corner of Coffey Street). The price tag was $8.1 million, with Diamond committing an additional $10 million via a loan from S3 Capital for “development of a condo building.” The realty press called it the highest buildable-square-foot price ever paid for a residential project in Red Hook. Given the R5 zoning in place (with no commercial overlay), these folks would need a super-duper variance and divine intervention to build anything other than four-story condos.

Most of the nine lots involved in this sale have long been vacant, aside from parked vehicles, and the four remaining structures with a total of six “dwelling units” on the northern end of the block are slated for immediate demolition. But it wasn’t always a depleted wasteland.

Old maps indicate that housing sprang up on the block a few years after the Civil War when Erie Basin, at the southern end of Conover, was completed, joining Atlantic Basin to the west a giant employment engine. The row of three- and four-story mixed brick and wood houses erected on Conover were not investment properties. They were sold to shopkeepers who lived above their storefronts: a grocery, multiple bars, candy stores, a tailor. They rented out one or two floors above them, a limit of one household per floor. All the male tenants were employed nearby in the shipyards, a short walk away, mostly as laborers and longshoremen, with some mechanics, clerks, watchmen and lightermen (who operated barges to offload cargo). The original inhabitants were all Irish and German immigrants.

The world of these Conover Street denizens was very circumscribed. Births, weddings and deaths, as well as the suffering they caused or endured, all occurred very close to home. And based on hundreds of newspaper clippings, every human calamity befell the struggling inhabitants of this block. Murders by pistol and knives. Suicides by hanging and drowning. Lots of drownings. Madness, incapacitating work accidents, infant deaths, assaults, rapes. Below is a brief sample of the more noteworthy incidents.

On Tuesday evening December 5, 1876, Hugh O’Brien of 197 Conover Street decided to see a play at the Brooklyn Theatre, located on Johnson Street (just east of Court Street in Cadman Plaza, near where the Supreme Court building now stands). There was a horse-drawn three-cent trolley on Van Brunt Street, a block from O’Brien’s home, that would have taken him to Hamilton Avenue and a transfer to a downtown trolley. The late-starting show was a near sellout, but young Hugh managed to buy a cheap seat in the top balcony. About eleven o’clock, a fire broke out backstage and quickly ignited the curtains. Smoke billowed out, up to the ceiling and engulfed the balcony. There was only one stairway down. Hugh didn’t stand a chance. He and 300 other souls perished in Brooklyn’s worst tragedy – that is, if you don’t count the departure of the Dodgers.

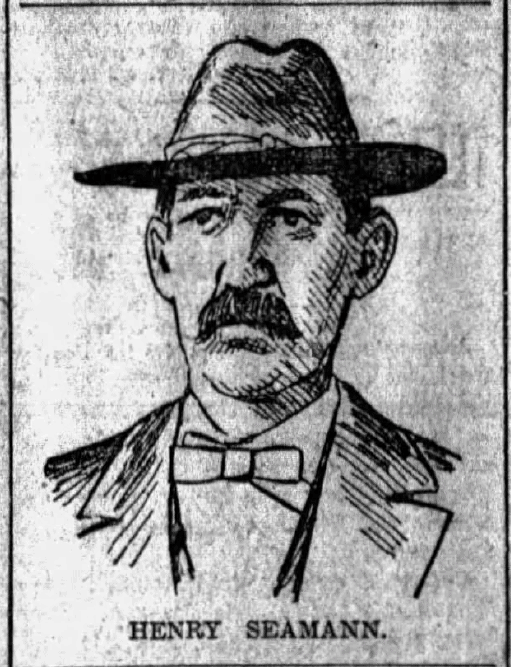

Speaking of which, on Saturday, April 27, 1902, Henry Seamann, a ship’s blacksmith and the only citizen of Conover Street who was ever called “prosperous” by the press, decided he was going to see his favorite baseball team, the Brooklyn Superbas. They played in Washington Park along the banks of the Gowanus Canal at 3rd Avenue and 3rd Street (now occupied by Whole Foods), with the ballpark extending up to 4th Avenue and 4th Street. The Superbas would abandon this notoriously smelly venue for Ebbets Field a decade later and become the Robins, the Trolley Dodgers and then simply the Dodgers. But when Henry got to 3rd Street, he was disappointed to learn that the Superbas were out of town, so he decided to go to Coney Island instead. He was last seen boarding the electrified Smith Street trolley heading to the shore. Eleven days later his decomposed body was found floating in the Erie Basin. Folks speculated he got three sheets to the wind at Coney Island and somehow wandered off a pier on his way home to 199 Conover.

Speaking of which, on Saturday, April 27, 1902, Henry Seamann, a ship’s blacksmith and the only citizen of Conover Street who was ever called “prosperous” by the press, decided he was going to see his favorite baseball team, the Brooklyn Superbas. They played in Washington Park along the banks of the Gowanus Canal at 3rd Avenue and 3rd Street (now occupied by Whole Foods), with the ballpark extending up to 4th Avenue and 4th Street. The Superbas would abandon this notoriously smelly venue for Ebbets Field a decade later and become the Robins, the Trolley Dodgers and then simply the Dodgers. But when Henry got to 3rd Street, he was disappointed to learn that the Superbas were out of town, so he decided to go to Coney Island instead. He was last seen boarding the electrified Smith Street trolley heading to the shore. Eleven days later his decomposed body was found floating in the Erie Basin. Folks speculated he got three sheets to the wind at Coney Island and somehow wandered off a pier on his way home to 199 Conover.

Four years after Seamann’s plunge, the New York press eagerly reported the sad plight of Mary Finn who lived at 187 Conover, six doors down from Henry’s widow. Mary’s husband had lost his job in the shipyards at the end of the summer, but now, on November 16, he was starting work again. Alas, the Finns’ four crumb-crushers desperately needed food, so Mary took a day job housekeeping for a Mrs. Nolan on Henry Street, a 20-minute walk away. Carrying her youngest on a cold morning, Mary laid the child on a sofa while she worked, and stole a diamond pin from Nolan’s dresser worth $150 (New York Times) or $200 (Brooklyn Citizen) – $4,600 to $6,100 in today’s coinage. She got two bucks for it at George Thain’s pawnshop on Court Street & Hamilton Avenue, money she used to buy “a warm cloak for her baby and some food for the other little ones.” Finn told Thain she would return late Saturday, once her husband was paid, to retrieve the pin.

But she was arrested as she walked home, “booked and measured” while still holding her baby – an event the press would sarcastically headline as: “Police Think Mrs. Finn A Dangerous Criminal!” The judge, based on the pleadings of a sympathetic probation officer, sent Mary and her child (still “clutched to her breast” in the courtroom) off to a woman’s shelter not far from the site of the Brooklyn Theatre – where a new structure now housed the Brooklyn Eagle, whose reporters somehow missed this story. But wait, there’s more: the judge who released Mary was furious! How could a pawnbroker give poor Mary Finn only two dollars for that jewelry? He issued a subpoena to have detectives drag George Thain before his bench to answer for this outrage. Of Thain’s fate, we have nothing more to report: by the following day, the press had moved on.

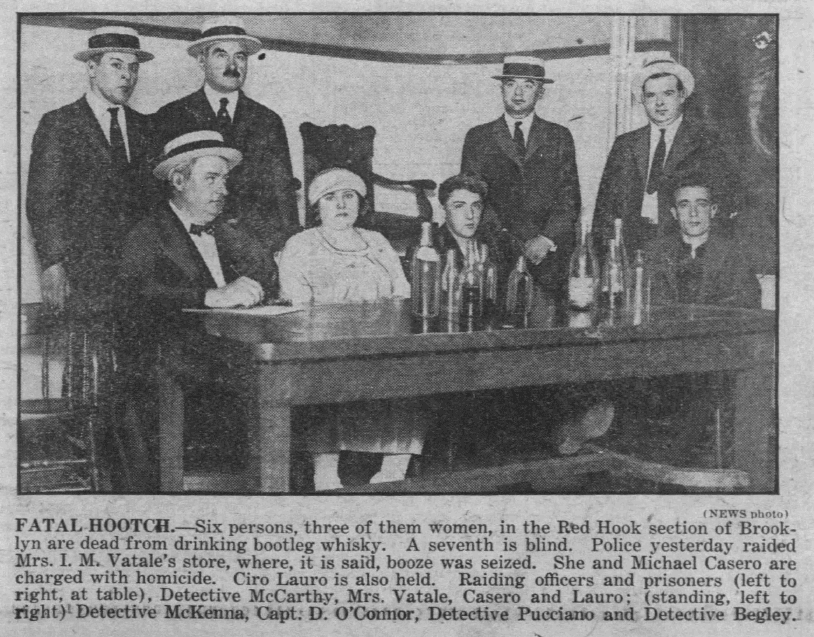

On Monday, September 3, 1922, two years and nine months after the onset of Prohibition, people in Red Hook started getting sick from alcohol poisoning. Within a matter of days, nine people had died, and others were going blind. On Thursday afternoon, detectives investigating the matter at Dikeman and Conover Streets suddenly heard a woman, Sigma Johnson, shriek from inside her home across the way, “I am blind!” While being rushed to the hospital, where she died in her 32nd year, Sigma told detectives she bought her booze from Jennie Johnson’s cafe at 199 Conover. In law enforcement this is called a lead. Within hours, 50 lawmen, empowered by the District Attorney to act without search warrants, “given the dire emergency,” fanned out from the Johnson storefront and raided all the buildings up and down Conover and the side streets. Their focus was on the many “cafes” (formerly bars, liquor, candy and grocery stores) that had been selling bootlegged whiskey to the locals – a very brisk business ever since Red Hook went dry. Enforcement had been difficult for the Feds and the patrolmen they enlisted because to make an arrest, you had to be served a glass of booze (it cost a quarter or 50 cents depending on the quality). But if you were a stranger, well then, there’s the door, bub, right behind you.

On Monday, September 3, 1922, two years and nine months after the onset of Prohibition, people in Red Hook started getting sick from alcohol poisoning. Within a matter of days, nine people had died, and others were going blind. On Thursday afternoon, detectives investigating the matter at Dikeman and Conover Streets suddenly heard a woman, Sigma Johnson, shriek from inside her home across the way, “I am blind!” While being rushed to the hospital, where she died in her 32nd year, Sigma told detectives she bought her booze from Jennie Johnson’s cafe at 199 Conover. In law enforcement this is called a lead. Within hours, 50 lawmen, empowered by the District Attorney to act without search warrants, “given the dire emergency,” fanned out from the Johnson storefront and raided all the buildings up and down Conover and the side streets. Their focus was on the many “cafes” (formerly bars, liquor, candy and grocery stores) that had been selling bootlegged whiskey to the locals – a very brisk business ever since Red Hook went dry. Enforcement had been difficult for the Feds and the patrolmen they enlisted because to make an arrest, you had to be served a glass of booze (it cost a quarter or 50 cents depending on the quality). But if you were a stranger, well then, there’s the door, bub, right behind you.

This warrantless dragnet yielded results, however: Hundreds of gallons of alcohol were seized, and the fatal wood alcohol was found in Irmelinda Vitale’s cafe at 149 Conover. She, Jennie Johnson and four others were arrested. Initially charged with homicide, they eventually were convicted of a mere violation of the liquor laws after the DA realized all the witnesses had gone toes up. The fatalities on the block included Annie Morris, age 42 (mother of five children); William Strelitz, a longshoreman; Michael Keenan, age 40; and Theresa Martin, age 26.

These were not the only alcohol-induced fatalities that year. Take the curious case of Peter Fiore of 197 Conover, who was arrested two months earlier on July 3 for possession of alcohol and an unregistered revolver. Fiore was released and scheduled for arraignment on July 10, but his tearful wife appeared instead and told the court he died in a car crash on the Fourth of July – this according to the reporter for the Standard Union. But the Brooklyn Eagle’s courthouse correspondent had a scoop: the fatal crash was just a face-saving tale because Fiore got so drunk, he fell out of a third story window to his death on Conover Street. He was only 29.

On the eve of World War Two, the block was starting to wear down and had been redlined by the banks. The 1940 photos taken for the City’s tax assessment records tell a mixed tale: the corner building at Coffey Street was abandoned, the glass in its windows riddled with holes. 199 Conover needed extensive clapboard repair. 189 Conover was a mess with a broken window, a boarded-up storefront, and some youngsters hanging out in front who looked to be auditioning for the Bowery Boys. 191 Conover was gone, but a dilapidated brick garage in the rear was inhabited, judging from a populated clothesline.

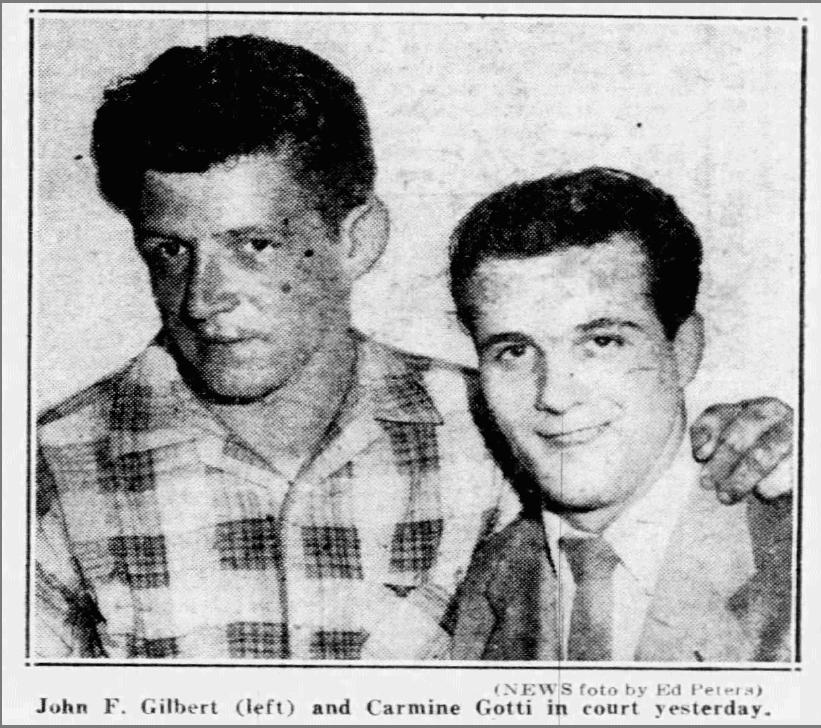

197 Conover Street looked outwardly well-preserved, however. And it had also remained relatively quiescent on the crime front since Fiore fell out of his window. But all that changed in September 1956 when 21-year old John Gilbert and his pal Carmine Gotti were arrested and convicted of the gunpoint robbery of a Bay Ridge gas station. Freed in March 1957 when a Bensonhurst teenager confessed to the crime, reporters asked Gilbert whether he was headed back home to Conover Street. No, he and Gotti were off to the movies in downtown Brooklyn, he smiled. Perhaps they went to see Alfred Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man, which had just opened, about a Queens musician wrongfully convicted of robbery based on an eyewitness misidentification. Alas and alack, John’s younger brother James Gilbert wasn’t misidentified when he was arrested three years later with a Coffey Street youth for a dozen stickups committed over a 10-day span at Christmas time.

197 Conover Street looked outwardly well-preserved, however. And it had also remained relatively quiescent on the crime front since Fiore fell out of his window. But all that changed in September 1956 when 21-year old John Gilbert and his pal Carmine Gotti were arrested and convicted of the gunpoint robbery of a Bay Ridge gas station. Freed in March 1957 when a Bensonhurst teenager confessed to the crime, reporters asked Gilbert whether he was headed back home to Conover Street. No, he and Gotti were off to the movies in downtown Brooklyn, he smiled. Perhaps they went to see Alfred Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man, which had just opened, about a Queens musician wrongfully convicted of robbery based on an eyewitness misidentification. Alas and alack, John’s younger brother James Gilbert wasn’t misidentified when he was arrested three years later with a Coffey Street youth for a dozen stickups committed over a 10-day span at Christmas time.

As manufacturing began to supplant homes, white-collar crime entered the mix. 189 Conover became office space for the Floyd M. Bennett Manufacturing Company in the 1950s. In 1960 the company fired workers who wanted to join the Seafarers International Union, prompting a fine by the National Labor Relations Board. By 1967, the A. G. Ship Maintenance Corporation had made 189 Conover its new office space in Red Hook and bought most of the surrounding lots. In 1978, the Waterfront Commission fined A.G. $130,000 for overcharging its customers in the Basins.

1983 photos show that almost all the Conover homes were gone. 185 Conover, the four-story corner brick building, was literally a shadow of its former self, since it had been replaced by a two-story structure. In 2005 A.G. Ship Maintenance consolidated its operations at its New Jersey location, selling its nine Conover Street lots to the Red Hook Building Company. And in December, Red Hook Building decided to pass the baton. Manufacturing is dead, at least right here. Residential is back. But years from now, as I pass the new condos, it will be hard not to wonder whether the new residents are seeing ghosts, like in those horror movies about developments built on old forgotten burial grounds.

2 Comments

Great read! Reminds me of the final scene of Gangs of New York; “No matter what they did to build this city up again, for the rest of time, it would be like no one ever knew we was here.”

Thanks, Mikey. That “Gangs of New York” quote would have made a great last line above!