Last Thursday I sat through almost three hours of a city process that will force permanent, sudden transformation on a neighborhood that has undergone only incremental change since the Dutch first showed up in Brooklyn.

Last Thursday I sat through almost three hours of a city process that will force permanent, sudden transformation on a neighborhood that has undergone only incremental change since the Dutch first showed up in Brooklyn.

The very next night I sat through two hours of something quite similar, albeit on a smaller scale.

The one constant in both cases was the willingness of the same council member to entertain, or perhaps even promote, greater density in the name of affordable housing.

The first meeting began with a patient presenter from the Department of City Planning going through their latest iteration of the rezoning of Gowanus. I kind of felt sorry for him. It’s not his fault that Gowanus will be going the way of Williamsburg, but he’s the one who has to deliver the bad news to the civic activists who are fighting a losing battle.

In the old days (back when I was the age of today’s hipsters), Gowanus’ main import was as a conduit to Park Slope for those like myself who lived in places like Boerum Hill. Aside from the housing projects, Gowanus was mostly home to small industry, drug dealers, and scrap metal places. In fact, a way of life for some addicts back in those days was to steal anything metal from anything abandoned and sell it to the scrap dealer for cash.

The only time in my life that I was searched by cops while laid out against a car was near Thomas Greene Park, back in the day. Prostitutes used to hang out in Gowanus, and the cops wanted to know what a white guy was doing walking around the park at 10 am. In those days, my office was right near where the Barclay Center is now, and I started parking in Gowanus to force myself to take a daily walk. Sanitation Commissioner Norman Steisel was picked up around that time for soliciting sa prostitute, so I guess that made me suspect as well.

That was in 1997. Just a dozen years later is when the percolating real estate markets to the east and west of Gowanus – Park Slope and Carroll Gardens, respectively, was spreading to the conduit. A 2009 rezoning plan was developed but put on hold when at about the same time, Congesswoman Nydia Velazquez finally took action to clean up the canal and successfully had it declared a Superfund site. I remember being curious why the Bloomberg administration fought so adamantly against the Superfund, but now I see that it was because it postponed the rezoning, making the developers wait a little longer.

A little more background: In 2003, the Bloomberg administration put through a downzoning of Park Slope. The wish of the homeowners was to prevent large developments from coming into the neighborhood – in other words, to preserve the neighborhood character. In exchange, 4th Avenue was upzoned which allowed 12 story buildings to replace much more humble residences, many of them lived in for years by relatively poor families. Rezonings make the same land worth more, and the small buildings were bought up en masse by developers amassing plots to build large buildings upon. The sanitization of the neighborhood left it ripe for development.

This was a point in time when Brad Lander was a well known community leader as head of the Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC), an affordable housing corporation. FAC was founded in the late 1970’s, when urban blight caused mass abandonment of properties. The city was just about giving away vacant lots and abandoned buildings to local development groups to create housing that would bring back communities. As the neighborhoods developed, the problems changed. By 1996, Lander was quoted in the NY Times saying “’The mission of the Fifth Avenue Committee is to preserve the racial and economic diversity of lower Park Slope and to insure that all residents benefit from the area’s development,’’ he said, ‘’which means to make sure low-income people are not displaced.’’

The 2003 rezoning did not require developers to give back anything to the community in exchange for the opportunity for profit given to them. There was no requirement for any street amenities, or for any affordable housing, much to the chagrin of Lander and the then local councilman Bill de Blasio.

Mandatory inclusionary housing was not a city policy at that time, although it had been required in certain rezonings. As the Times wrote in 2003, “Inclusionary zoning has been tried in the most dense residential zones in Manhattan, Ms. [Amanda] Burden said, but has failed to produce many moderately priced apartments. Advocates and developers say that is because there are more attractive tax incentives available for constructing low-cost housing that do not exist in the other boroughs, and not because the concept is flawed.”

Skip ahead a dozen years and de Blasio is the Mayor and Lander, who succeeded de Blasio as the local councilman, occupies the second highest position in the City Council. The mayor, backed by the City Council, passes the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) bill. This forces developers to include affordable housing in any project that enjoyed greater density due to an upzoning.

Lander, whose career is grounded upon affordable housing is its biggest proponent. Nobody doubts his sincerity, at least I don’t. MIH will prevent the 2003 Fourth Avenue debacle from ever happening again.

But a new problem is created. By shifting the responsibility for building affordable housing to private developers, a city manager/politician looking to create more affordable housing has to, by default, allow for out of scale buildings that redefine communities.

Hence a steady stream of dissenters heading to microphones throughout public hearings all over the city, complaining about losing their quirky neighborhood and its history to sterile high-rise developments.

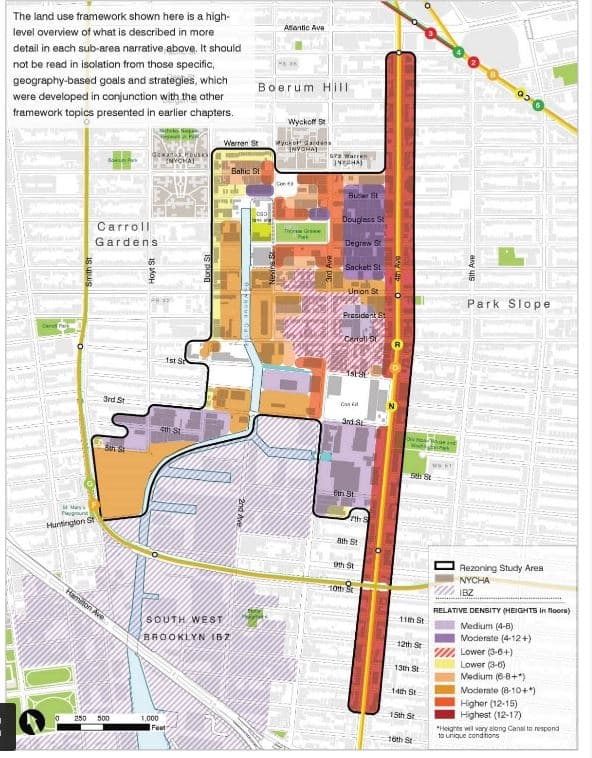

The Gowanus rezoning, with each succeeding plan revealing ever increasing building heights (2009 – 12 stories, 2018 – 17 stories, 2019 up to 30 stories), is a foregone conclusion. The gritty Gowanus of today will be a memory. As a businessman who spoke at the meeting said, “it’s difficult to operate a construction business from the fourth floor,” noting the replacement of one and two story bildings with towers.

It must be scary to have your neighborhood at the mercy of a rezoning. We live in a world that embraces change, but extreme change will usually be disconcerting, to say the least.

The very next night, I found myself on Columbia Street at a meeting of locals upset at a smaller rezoning of 41 Summit Street, right next to the Chase Bank on Hamilton Avenue. What happened is that a few years ago, the feds auctioned off a building that had been seized in the early 1990’s because of its use in selling cocaine, probably right off the nearby ships.

I noticed a couple of guys in the building, sitting around a grill. They weren’t too fancy looking, just a couple of local investor types (as was, by the way, Greg O’Connell back in the beginning of his real estate career). I remember what the place looked like right before the auction. It was frozen in time, a few dusty coffee roasting machines, and a giant safe drilled through by the Feds twenty years earlier. If you go online, you’ll see that they put in new floors and a kitchen and tried to rent it out as a commercial loft.

Someone must have told them that they could make a lot more money having it rezoned as a five-story residential building. In today’s market they could get as much as a million and a half per floor if they condo it. I’m guessing that they were told by their real estate attorney, someone from the zoning specialist company Sheldon Lobel, LLC, that they might as well shoot for the moon and try for permission to build seven or eight floors.

At five floors, nobody in the neighborhood would have complained – it’s pretty much in scale with the area. But, in order to avoid the illegality of what is called ‘spot zoning,’ they added two adjacent lots to their application – the Chase property and the building next door that recently housed a bagel shop on the first floor. The other owners did not appear at any hearings, but were the rezoning to go through, the lots could be built together to create an even larger monstrosity, but – because of MIH – would now require a few affordable apartments in the mix.

This would cast a large shadow on the beautiful community garden on the corner. Dave Lutz told us at the meeting that they have many people who have boxes in the garden and grow tomatoes and vegetables in the areas that get sun. A building would end that.

Having a seven story building jutting out in a line of houses about half that size would be ugly, and architecturally inappropriate.

Finallyh, once one seven story building is allowed, it will be that much easier to get permission to build five or six more outsized projects in the vicinity – there are still vacant lots in the vicinity.

That’s what Community Board 6 thought when the plan was presented to them last year. It was voted down 15-1. Borough President Eric Adams heard the plan next, and agreed with the neighbors that five stories was good enough. But next in line was the Department of City Planning (the same people shepherding the Gowanus project), and for a technical reason they decided to allow seven stories.

The last hearing before this plan becomes reality is this Wednesday at the City Council. An emergency neighborhood meeting was called on the Friday before to figure out how to save this portion of the Columbia Waterfront District. We got together last Friday at the offices of the Carroll Gardens Association, at 201 Columbia Street. For about an hour we discussed different strategies to try and convince the councilman Brad Lander, that this was no good. People will take a day off from work and go testify. Additionally, letters and emails from the community will be sought to show the Council, and Brad, what the neighbors think.

And then Brad himself showed up. That’s when I found out for myself why this plan, which, back in October I called crazy, here in this paper, has a chance of becoming reality.

Brad told us that he understands how much a neighborhood can love its garden, and that he also understands how a neighborhood could want to preserve its height restrictions, and keep the opportunity to see the blue sky, and that he could even understand why a neighborhood might not want to overcrowd its schools and transportation systems. But he admitted to one thing that might override these concerns in his mind.

And that is affordable housing.

Brad kind of looked dreamy eyed as he contemplated adding to the number of affordable rate apartments he might possibly be remembered for during his tenure as a city councilman. He said that he might, maybe, change his thinking when he makes the decision about this application, but only if the city council lawyers tell him that MIH kicks in at the five story zoning level.

In this issue of the Star-Revue, we profile 11 new buildings built in Red Hook over the past couple of years. All of them share one attribute – they were all built within existing zoning regulations. Meaning all are five stories or less.

One can imagine how different Red Hook would look today were Brad the councilman. We’d have a high rise district on Van Brunt Street for sure. Luckily, our councilman, Carlos Menchaca, who is also a big believer in affordable housing, also understands that there can be a balance between change and tradition.

One Comment

When planners and Politicians decide that there is just one criteria that matters in planning—Affordable Housing, and that it matters to the exclusion of such basic things like light air and open space, one can only conclude that these folks are fine with providing, lifeless, joyless places for people who have limited choice for housing. The Gowanus schemes looks more like a zoning plan to foster things like mental health problems and drug abuse. But don’t worry Mr. Politician, the developers who you are multiplying land for will make sure your political career will advance and you will have much choice in where you will live.