In June, 2014, at a meeting at PS 15, Amy Peterson, Mayor de Blasio’s head of the Build It Back program, spoke to residents about the Build It Back program.

We wrote at the time: “New York City’s answer to the major damage from Hurricane Sandy was meant to offer millions of dollars of assistance to families and businesses reconstructing their homes in the aftermath of the disaster. Five pathways were made available for victims: repair, repair and elevation, reconstruction, reimbursement, or acquisition.

However, a combination of factors including poor public communication, confusing qualification guidelines, and changing leadership neutralized the efforts of the program until recently. Amy explained that of the thousands of residents who sustained hurricane damage in Red Hook and Gowanus, only 121 had actually applied to the program. Of those, only eight had selected their assistance option.

Amy was being polite. A few weeks before that meeting, City Comptroller Scott Stringer held a session in the same auditorium as part of a six neighborhood tour he was making to hear firsthand the problems people were having. We wrote of that meeting: “Mary Kyle, from Van Brunt’s Dry Dock Wine and Spirits, found her element in the audience. She regaled them, saying that having to appear before Build-It-Back was like a trip to visit the great OZ – all smoke and no action. She almost broke into tears, saying that the alienation she feels from the city has been crippling. She was speaking both as a homeowner and business owner. “We need money – not cups of pudding!” was how she characterized the Sandy aid that she perceived since the storm.”

Stringer’s Build It Back study was issued March 15, and to say it is damning is to put it mildly. The 87 page report, available online, is a compendium of mismanagement, bad decision making, fraud and outright theft of city money by hired contractors.

Build It Back is a NYC program initiated by Mayor Bloomberg in 2013 to help owner-occupants of 1-4 family buildings that were ravaged by the Sandy floodwaters. Applicants, many from Red Hook, were initially encouraged by the city’s commitment to help them recover and rebuild their damaged homes. But that hope soon turned to utter frustration as they were led through an interminable process of paperwork which led to nothing.

“New York City’s response to Sandy was a case study in dysfunction,” Stringer said in his press conference to introduce the study. “During the course of this audit, I went to affected communities to hear first-hand the stories of the recovery from hundreds of City residents – from the endless delays, to the lost paperwork and the maddening lack of progress. With this audit, we present a new level of detail about how the City allowed consultants to run amok and what must be done to make sure these mistakes are never again repeated.”

The Bloomberg administration hired Public Financial Management, (PFM) a Pennsylvania based firm that boasts municipal clients throughout the US. However, they had absolutely no experience at managing disaster recovery, according to a September 2014 NY Times article. PFM went on to hire various subcontractors to perform the intake work – the application process that homeowners needed to go through. Complaints about the program caused PFM to be terminated in December 2013, the last month of Bloomberg’s term, but the subcontractors remained, but without contracts.

Stringer explains “If there are no valid contracts in place, the City has limited leverage over its vendors’ work and cannot hold them accountable for their performance. “

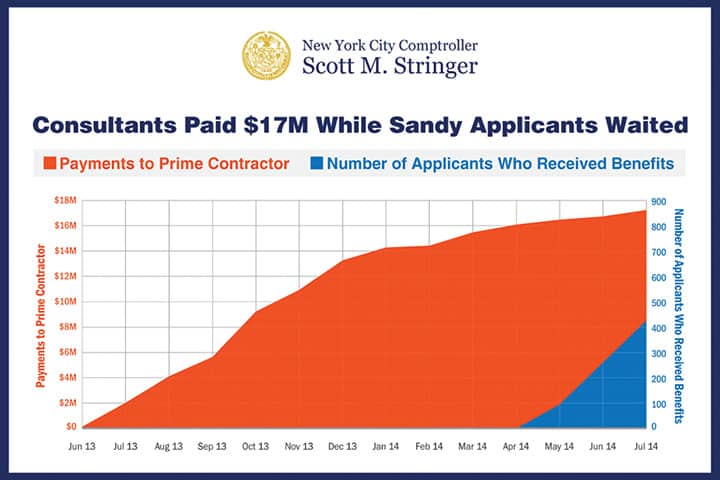

The city agency responsible for all oversight of Build It Back is the Office of Housing Recovery Operations (HRO). Before they were fired, PFM was paid over $17 million for their project management work. According to the audit, at least $6.8 million was paid for “work that did not conform to program requirements set out in PFM’s contract.” These were payments made for forms filled out by homeowners that were incomplete and useless. The incentive for all the contractors were to get paid for turning in forms. Whether the applicants were instructed properly in the filling out of the forms was not checked.

The NY Times article gave a hint at how this could have happened. “PFM brought in another firm that had worked on prior disasters, URS Corporation, to run the intake centers, which it staffed with temporary workers.

The custom-made computer system, into which all applications were to be entered and stored, was supposed to be delivered two to four weeks before opening day, a person involved in setting up the centers said. But it did not arrive until the night before opening day, leaving no time for any familiarization.

“Everybody was pretty much on their own, trying to figure it out themselves,” said a man who worked as a recovery specialist and also would only speak anonymously to protect his chances of finding a new job.

For months to come, records scanned into the computer system — proof of income, property ownership and storm damage — seemed to disappear.

“People were told to come back with the same info, and the same form,” the man said. “I apologized to them a lot, because it was frustrating for me as well.”

Abe Zeinali, who owns a multi-family dwelling at 187 Richards Street that is now empty of tenants except for himself and his girlfriend, is a case study of the frustration and fraud detailed in the Stringer audit.

He points out an additional problem not mentioned in the report. The longer his house stays unrepaired, the more expensive repairs become. He is worried that the structural integrity of his 1925 home has become an issue. After going through the familiar process of filling out forms and then refilling them as they became lost, he finally had a Build It Back supplied architect devise a repair plan – much of which Zeinali, who has engineering experience, provided. However, the plan fails to address the structural problems, meaning that the expensive repairs could eventually lead to his house falling down – and then “who is responsible” he says.

One example he cites is the basement boiler, which he replaced at his own expense. “It’s a heavy boiler, and they want to move it to the second floor,” he explains. “Such a heavy piece of equipment would damage the integrity of the second floor. The answer is to replace it with lighter units – which they refuse to consider.” Another example he mentions is the placement of the electric meters. “All the other houses on the block have their meters in the front – allowing for easy access in the event of another disaster. They insist on moving them to the back of the house. Why?”

He believes that there are no incentives for honesty and frugality in the whole process. The unsupervised contractors are more interested in billing than in performing an honest job. All he would like is a chance to discuss his rebuilding ideas with an honest city official with some honesty and common sense.

Indeed, even though Stringer’s report details cases of outright fraud, there is no recommendation for the city to ask the contractors for refunds. Stringer himself can’t believe that many of the same contractors are still on the city payroll.

While Stringer acknowledges progress in the program since Amy Peterson was brought into it in March, 2013, he says more should be done.

Recommendations include direct supervision. “City staff should manage the program more directly to ensure responsiveness, accountability and efficiency. Poor supervision of contractors allowed problems to snowball, costing taxpayers millions, while delaying critical relief.”

More specifically: “The City should explore ways to maximize the use of City resources rather than outside consultants for potential City-wide disasters. The City should have qualified and experienced staff to design, manage, and assess future disaster recovery efforts.”

The de Blasio administration was given an opportunity to respond to the report. They basically agreed, saying “HRO will follow an assessment process in the ordinary course of its emergency preparedness operations.”

It is now up to the City Council and the public to see that this doesn’t happen again – but that is of little consolation to the many thousands who continue to try and live in damaged homes.