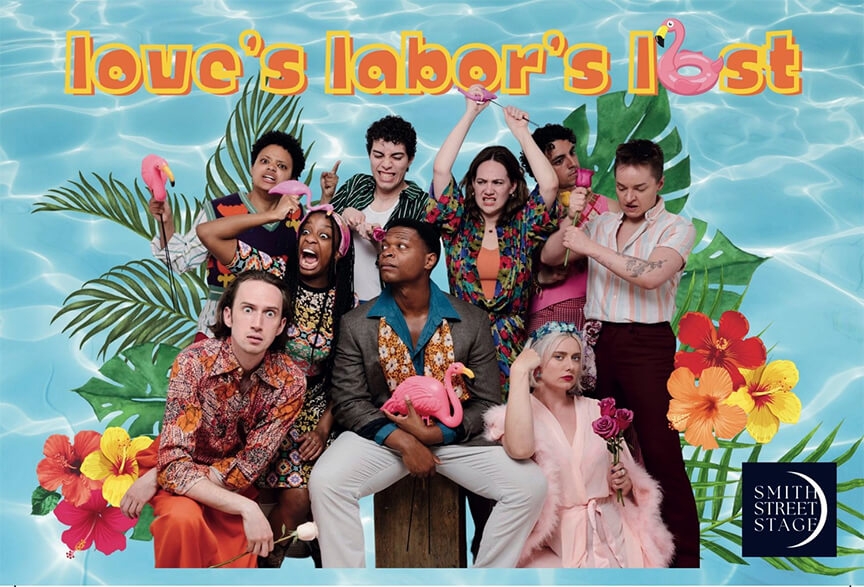

On June 5, at 7:30 pm, Carroll Park was filled, as usual, with children playing and parents catching up, but on the eastern side of the park, twinkly lights were strung from the back of the Park House and a stage, painted to look like a pool deck, was surrounded by folding chairs. It was Smith Street Stage’s first preview of Love’s Labor’s Lost, one of Shakespeare’s early plays, in which the King of Navarre (a province in northern Spain) and his three companions swear off women and other temptations for three years in order to focus on study; much like New Year’s resolutions, the oaths face quick deaths upon the arrival of the Princess of France and her three ladies, with whom the men are quickly enamored. Smith Street Stage’s modernized version of the silly play reached new heights when combined with excellent costumes by Nell Simon, and a clever portrayal of the lovers as reality tv show contestants (think Love is Blind, but with less alcohol), thanks to director Raquel Chavez.

During the first night of previews, about 40 attendees watched the performance, many of them under the age of ten. (By closing weekend, the crowd had swelled to about 200 attendees each evening.) Shakespeare’s language can be difficult, but even the youngest viewers were enthralled and eager to follow along. One young girl momentarily left her front row seat to let another child in the playground know he needed to quiet down; another young boy pleaded with his mother when she whispered that they could only stay for 20 more minutes. Despite its 400-year run, the play remains relatable and funny—young men swearing off women, only to immediately fall in love? A scene in which the fellows try to trick the girls by dressing as Muscovites (picture tracksuits, fur, and thick accents)? The humor is only cut short by the play’s tragic ending, when the Princess suddenly learns that her father has passed away.

The quality of the play’s acting and production will come as no surprise to Smith Street Stage regulars. The company, whose mission is to explore the works of Shakespeare and to render his plays clear and accessible to all audiences, has been providing the neighborhood with Shakespeare in the [Carroll] Park since 2010. Slowly making a name for itself, the company is able to be picky about its performers. This year, two of the main roles—the Prince and the Princess—were played by Amara Jamed Aja and McLean Peterson. Aja grew up in Kensington, Brooklyn, the son of Nigerian immigrants, and works as an arts educator off the stage; Peterson grew up in suburban Chicago, moved to the City at 18 to pursue her training at NYU, and has now lived in Prospect Lefferts Gardens for the past seven years as an artist producing everything from voiceovers to short films.

As trained actors, neither Peterson nor Aja was new to Shakespeare, but they agreed on the beauty of and the obstacles to the work that Smith Street pursues. The greatest challenge? The acoustics of an open playground. As Aja noted, “It’s humbling as an actor to realize you can ask yourself, ‘What’s my motivation? What chakra is my character moving from?’ but really, the audience just has to hear you.” Peterson agreed: “They told us that this is what it was going to be like. It feels like a personal attack when the siren comes through during YOUR monologue, but it comes for everyone.”

Joy and silliness

Ultimately though, Peterson and Aja were effusive in their praise of the people involved in the productions and the joy of the audience far outweighed any challenges. Both were quick to note that beyond the cast, the crew, directors, and production teams were also outstanding collaborators. “It’s a bunch of people who are really invested in working really hard to put on a good show. There’s joy and there’s play, silliness, and looseness; it’s absolutely not a high pressure room, but it’s clear that everyone cares a lot about doing something that we’re proud of, and I hope that people who come to the show can see both the level of effort, and receive the invitation to play and have a good time with us,” Aja noted.

On the future of community theater, both artists again agreed: theater should be accessible to anyone and everyone, it should be in your neighborhood, and it should be supported by the government. There is a keen awareness that their role as actors providing free plays is not widely valued. Aja adroitly noted the divide between values and resources: “I think that it is a tremendous mistake not to give these places, organizations, and people interested in creating entertainment, jobs, education, and contributing to the vibrancy of this place that we all claim to love, the resources they need, especially in a time and a place of such abundance.”

Smith Street Stage’s artistic director, Jonathan Hopkins, who co-founded the company with his wife, has loved Shakespeare since college, and recently deepened his study, completing a MA in Shakespeare during the pandemic. He’s open about his passion: “Even among Shakespeare nerds, I’m probably within a certain percentile of nerdiness.” Beyond his appreciation for Shakespeare’s writing though, he sees the plays as reflections of our own times, conflicts and problems, and therefore, as a source that we can turn to for insight, comfort, or guidance, or even to challenge our assumptions.

Hopkins is proud of the company and its incredible talent, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t see plenty of opportunity for growth. Love’s Labor’s Lost was the first time the company performed on a raised stage. The current funding “wish list” for the company includes being able to more regularly perform an indoor show (they currently have one about every other year, if possible, as it provides an opportunity to tell stories in a way that isn’t always possible outside), further improvements to the audience experience (more lights, more of a stage, more seats, etc), and to be able to pay their artists more (both McLean and Peterson both noted how thankful they were to Smith Street Theater for working so hard to pay them fairly, while acknowledging that the entire cast needed multiple jobs to make ends meet).

Looking forward, Smith Street Stage is already beginning to cast for its fall performance. The company will put on Richard II, directed by Katie Willmorth, at The Mark O’Donnell Theater (on Schermerhorn Street between Smith Street and Hoyt Street). Tickets will be about $25 (with additional discounts available). For Shakespeare lovers, it would be a pity to miss one of these excellent shows, and for everyone else, it would be a pity not to see just how fantastic local theater can be.