As State Senator, H. Carl McCall led a community protest against the threatened closing of Harlem’s Sydenham Hospital. The 1976 protest was necessary, as he said at the time, because “the community would not allow the policy of ‘municipal shrinkage’ to shrink our community.”

Today, McCall, as Chairman of the SUNY Board of Trustees, is leading a nasty battle to shutter Long Island College Hospital (LICH), ignoring court orders, community protests and the wishes of most local politicians. New patients are refused admission; existing ones have been coerced into leaving. Dozens of uniformed guards – many armed – have been stationed at the peaceful facility, intimidating the staff. One-time allies such as Nydia Velazquez and Leticia James are stunned by this turnaround of McCall – a man they once considered a friend.

Humble beginnings

Herman Carl McCall was born in 1935 into Roxbury, a once segregated Boston neighborhood. His father was a railroad worker who left the family after losing his job. McCall credits his success to his mother, who stressed education, and to the local church, where he met future senator Edward Brooke. Brooke told the young McCall that he would help him get into Dartmouth College, and he did. After college, McCall studied in the seminary and became an ordained minister.

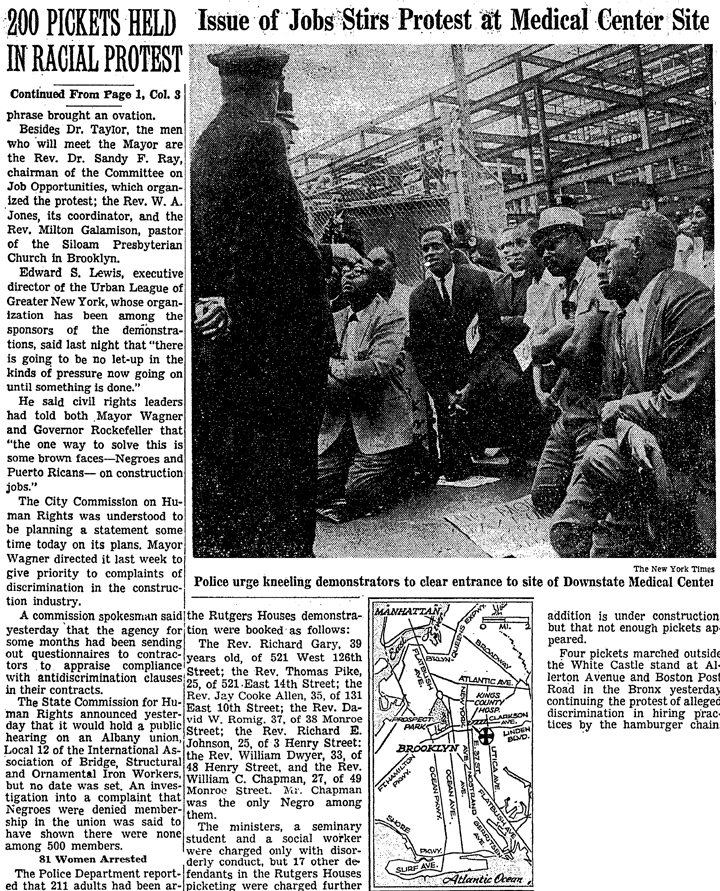

After a brief spell teaching high school in Boston, he decided that New York offered greater opportunities. A job offer with the NY Mission Society took him to Brooklyn, where he did community organizing and social work. One of his early successes was integrating a construction project at central Brooklyn’s Downstate Medical Center. The local clergy were concerned that there were no black or Latino employees. After some unsuccessful picketing, McCall, as he tells it, decided to try civil disobedience. He led a group of 200 who were arrested for blocking the entrance to the site. The large protest made the cover of the NY Times, and the next day Governor Rockefeller met with the group to work out a solution.

NY Times article, 1963

In 1966, Mayor Lindsay appointed McCall to head NYC’s Council Against Poverty. An initiative inspired by Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty, this position gave McCall his first city-wide platform.

McCall penned a New York Times piece in November 1967. He wrote, “From the beginning there has been a debate within the Negro community over the value of the antipoverty program. Many Negroes see the program as a response to the civil rights drive of the early sixties. They watch as former civil rights workers find employment in it, and as civil rights groups are funded to operate projects. They suspect that the basic purpose of the program is to dampen the Negro drive for equal rights. Others believe that the program is designed merely to ‘cool’ tempers in the Negro community, especially in the summer, rather than to promote real change and genuine opportunity.”

McCall was already being described by the Times as a “prominent Negro spokesman on poverty and attainment.”

In 1968, he was named Deputy Administrator of the city’s Human Resources Administration (HRA). There, McCall was faced with the problem of funding. As Vietnam spending began taking up more and more of the Federal treasury, state grants were cut. McCall had to fight for city and state money to make up the difference. Lamenting priorities, he said, “Such fund juggling is no way of doing business, I know. I am sure that’s not the way the Defense Department, for instance, works. But it’s that way with the war against poverty.”

He left HRA in November 1968. He kept his fingers in politics as co-director of the Citizens Voter Registration Campaign. He worked to seek change in voter registration laws, making it easier for the poor to register to vote. By 1970, he was already thinking about statewide office, but deferred a race for Lieutenant Governor to his Harlem friend Basil Patterson.

Buying into Amsterdam News

In 1971, McCall, along with Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton and others, purchased the Amsterdam News, NY’s leading African-American newspaper. He presided over the editorial board. He joined with many of the same people to start Inner City Broadcasting, which bought two city radio stations, including WBLS. In addition to being a good financial investment, it cemented McCall’s relationship with the city’s black political leaders, which included David Dinkins, Charles Rangel, Basil Patterson and Percy Sutton.

McCall became a rising star, both in the black community as well as the general public because he was appealing to a broad spectrum of peoples. He was well-spoken and handsome, cutting a polished figure to voters.

In 1974, he ran against Harlem’s State Senator, Sydney von Luther. Luther, a self-described gadfly, once challenged a fellow senator to a duel. McCall had the strong backing of his friend, Borough President Sutton, and won the seat.

Describing the campaign, a NY Times reporter questioned his affluent lifestyle – a co-op on Riverside Drive and a house on Martha’s Vineyard. He rallied for the underserved lower class, yet had exemplified the existence of wealth. McCall’s response was to say that some voters on the West Side “think I should run around in dungarees to show people how well I relate to the community.”

Sydenham battle

McCall was instrumental in forming a coalition to save Sydenham Hospital. Sydenham, a city hospital, operated at a deficit, but was considered essential for the underserved area. McCall led a well publicized march through Harlem decrying the city’s plan. He organized a 5,000 man march and led a campaign to keep it open. He viewed this as a racial issue, saying that the black community was “picked out to be destroyed because it was believed to be powerless.”

Now, McCall sits at the head of the SUNY Board of Trustees and aims to do exactly what he fought against at Sydenham. The Red Hook community has already been declared underserved medically while LICH remains open. If the closure plan is successful, Red Hook becomes even more underserved, as do the communities of Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, Gowanus, Downtown Brooklyn, Boreum Hill and the Columbia Waterfront District. McCall is now sitting on the opposite side of the fence.

The hospital ended up closing in 1980, leaving Harlem with just one facility. Mayor Ed Koch, reminiscing about Sydenham years later, said “I think we saved $9 million a year. Was it worth it? Was it worth all the heartache and the picketing and the screaming and the wounded feelings? The answer is no, it was not.”

Being a Democrat in the traditionally Republican State Senate is not the best place to advance one’s career. Just as he left Boston for New York, McCall began looking for his next opportunity. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter picked McCall to be a delegate at the United Nations. The Times reported that McCall: “has been viewed as a moderating force in the Black and Puerto Rican Caucus here. But he has reportedly alienated many of his minority-group colleagues by what some of them privately say is ambition and arrogance. Those familiar with his thinking said Senator McCall had decided that his political possibilities were limited from his spot in the Senate minority and that he had decided it was time to seek a platform elsewhere.”

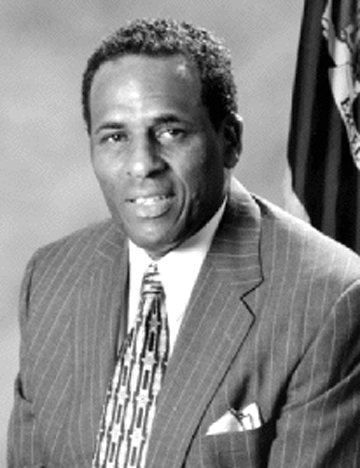

McCall in 1999

In 1982, McCall ran for Lieutenant Governor as Mario Cuomo’s running mate, but lost in the primary to Alfred Del Bello, Ed Koch’s running mate. Cuomo won his election and appointed McCall as NYS Human Rights Commissioner. He held that position until 1985, when he resigned to take a private sector job with Citibank. His job was to lobby politicians on behalf of the bank. During those years that Citibank was aggressively expanding the boundaries of banking and needed banking regulations to follow suit. McCall stayed at Citibank for six years, adding valuable business experience to his resume.

McCall was supportive of Governor Mario Cuomo. Cuomo, in turn wanted McCall as Lieutenant Governor in 1990. Cuomo won, but McCall did not.

In 1991, Mayor Dinkins named his long-time friend President of the Board of Education. It was a controversial time for the Board as the school system was dealing with condom distribution, AIDS and other social issues. The board was often split with McCall having to mediate – often in vain.

In the spring of 1993, State Comptroller Ned Regan announced that he was leaving the job, and McCall was chosen to fill out the term. He became the first African-American to occupy statewide office. The Times wrote that McCall “has always enjoyed strong support among moderate and liberal whites and Hispanic people. He drew on that support in beating out a white liberal, Carol Bellamy, as Assembly Speaker Saul Weprin’s choice for comptroller.”

The 1994 gubernatorial race became a choice between a fourth term for Cuomo and a little known Peekskill politician, George Pataki, whose main strength was Cuomo’s growing unpopularity.

During the same race, McCall ran against Republican conservative Herb London for City Comptroller. His campaign was masterminded by future Obama advisor David Axelrod. McCall ran attack ads against London, emphasizing his positions against abortion and for guns – although neither had anything to do with being comptroller, a position of auditing and investing state funds. London, in turn, attempted to misconstrue McCall as anti-Semitic. The NY Times condemned London’s tactics and endorsed McCall.

This time, Cuomo lost but McCall won. He became the first African-American to win a statewide election. His visibility grew statewide and he began to be seen as a potential governor.

The NY Times reported in 1996: “People in both major parties say that Mr. McCall would make a formidable candidate. As the only elected Democrat on the state level since the Republicans took the two other top offices in 1994, he has tried to use the Comptroller’s platform to cast himself as a fiscal moderate who can be trusted with taxpayer money.”

After testing the waters for the 1998 governorship, McCall decided instead to remain Comptroller. In an election notable for the election of Charles Schumer to the US Senate, McCall won re-election, as did Pataki.

Fashion Institute

McCall’s wife, Dr. Joyce Brown, was soon afterwards appointed president of Manhattan’s Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), a position she still holds today. FIT is one of SUNY’s 64 statewide campuses.

At the time, some questioned the appointment. The Times wrote, “While no one questions her qualifications, there has been speculation in political, fashion and academic circles that the appointment was approved by the State University Board of Trustees in part because Gov. George E. Pataki, who controls the board, wanted to dissuade her husband, the state’s highest-ranking Democrat, from campaigning vigorously in last month’s election and drawing a strong black turnout that could help Democratic candidates. Dr. Brown herself repeats another theory making the rounds: that Mr. Pataki did not want Mr. McCall running against him for governor.”

In a front page Village Voice article a few years later, it was revealed that the Brown spent $529,000 of public and grant money redecorating their FIT living quarters – a 4200 square foot penthouse. Free housing is a perk for all SUNY presidents. The renovation – which included a $4,500 refrigerator and $20,000 worth of rugs – was justified by Brown as necessary for entertainment of potential donors. It is also an indication of the lifestyle the McCalls were comfortable with. In addition to this new home, they owned condos on Central Park West as well as a million dollar estate in Duchess County, which McCall bought partly to have his own tennis court. McCall had even more palatial quarters in mind, though.

It was clear that a run for governor was next. A January 24, 2000 article in the Times posits McCall’s entry into the 2002 primary as a sure thing. It noted that his only possible competitor in the primary would be Mario’s son, Andrew.

Much to the dismay of McCall’s political friends in the black community, Andrew Cuomo decided to run. Blessed with the Cuomo name, eight years in Washington working for Bill Clinton, and a Kennedy wife, Cuomo raised a lot of money. The Times noted that Cuomo’s style was not just to take the money from his donors: “They want to be wanted for their ideas, their thoughts. Most politicians don’t give that. Andrew does.’’

It was a highly contested campaign, and much of the money that McCall had set aside for the November race was spent for the September primary. Although Cuomo was reluctant to badmouth his fellow Democrat, he instead enlisted others. Leftwing professor Cornel West, speaking at a Cuomo event, announced: ‘’I think Carl McCall is a decent man, he is a good man. But he is a timid and hesitant man. We need an aggressive progressive.’’

Pay-to-play

Cuomo did attack McCall for engaging in the “pay-to-play” system of politics. McCall was responsible for investing the state’s pension money. This is money taken out of pay to be used for the retirement checks of state workers. The state invests this money seeking high returns to make sure that there will be enough to pay the pensions. Typically, pension money is invested in real estate, corporate and government bonds, US and foreign stock markets, world currencies, and “investments in companies not publicly traded [including] investments in new companies, categorized as venture capital, established companies seeking capital for expansion, categorized as corporate finance, special situations funds that invest in specific industries, such as energy and power, or follow other strategies.”

This puts the comptroller in constant contact with private firms seeking business from the pension fund. Cuomo attacked McCall “daily” according to the Times, for accepting campaign contributions from companies he favored with investments.

By the beginning of September, Cuomo saw he couldn’t win. Rather than take the loss, he withdrew before the election. McCall did not join Bill Clinton and an uncomfortable Charles Rangel at the announcement. Asked about a role for Cuomo during the campaign against Pataki, a bitter McCall said: “He’s joining 700 other prominent Democrats in the state who have endorsed me.”

Outspent by Pataki, with third party candidate Tom Golisano taking away upstate Democratic votes, McCall lost the November election by a wide margin. The only counties he captured in the whole state were in NYC.

Following his defeat, McCall turned his full attention to making money. In 2001, according to tax returns released by the McCall campaign, he and his wife jointly earned $472,000, with Mrs. McCall earning two thirds of it.

McCall joined the boards of various private corporations. He was named Vice Chairman at Healthpoint, a private equity company invested in the health industry. He resigned after the company became involved in some scandalous activity involving corrupt Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich.

He next started his own investment company, Convent Capital. This company also became tarnished as a result of a Cuomo investigation, which may have drawn the two together.

The black political establishment felt burned by Cuomo’s opposition to McCall in the 2002 race for governor. McCall remained bitter. In 2006, Cuomo ran for Attorney General. Asked about the race, McCall said, “If [Cuomo] has any prominent African-American support, I haven’t seen any sign of it. Many people I talk to are not positive about his campaign for attorney general.”He also added, “I know I couldn’t support him.”

However, McCall’s position changed in 2009. It was obvious by then that Cuomo was going to run for governor, and McCall had a change of heart. “People have misread what happened in 2002, and they have tried to make it appear like that was some kind of racial assault,” McCall said in an interview. “Andrew Cuomo ran against me because he thought he could win. I think if he runs against David [Patterson], he’s not going to run against David because he’s black; he’s going to run against David because he thinks he can win.”

By October, McCall was not only endorsing Cuomo, but campaigning for him as well. This was after Cuomo shocked McCall by naming his investment company in a corruption scandal.

As far back as 2002, Cuomo was talking about taking on “pay to play” – a term for political kickbacks. In May 2006, the Attorney General’s office published a list of 100 unregistered firms that served as unregistered intermediaries between the Comptroller’s office and investment firms.

This scandal, involving financial firms using political consultants and lobbyists – instead of licensed brokers to win pension fund business, ended up sending Comptroller Alan Hevesi and political advisor Hank Morris to jail.

McCalls firm had accepted a $48,000 fee for steering a client to the Comptroller’s office. While named, Convent Capital was never prosecuted. Soon afterwards, McCall went public with his newfound lack of bitterness.

In the 2010 governor’s race, Republican opponent Carl Paladino said, “Andrew Cuomo should be prosecuting Carl McCall, not accepting his endorsement. Carl McCall and his firm, Convent Capital, took a sizeable fee for securing state pension funds without being registered with the SEC as a broker. Andrew Cuomo prosecuted Ray Harding and Hank Morris for doing the exact same thing. Why not McCall?”

Paladino, a Tea Party favorite, said lots of other things, including that he was going to clean up Albany with a baseball bat. And again, about the Cuomo/McCall relationship, “These two career politicians don’t even like one another, but they’ll scratch each other’s back in order to maintain power and line their pockets.”

Cuomo became governor in 2010 and immediately named Carl McCall, Nydia Velazquez and Felix Rohatyn to lead his transition team, saying in a press release, “Each of them brings to the transition a wealth of knowledge and a deep understanding of the challenges facing the State of New York. Lieutenant Governor-Elect Duffy and I look forward to working with them to ensure that we attract the best and brightest talent to the Cuomo Administration.”

In November 2011, Cuomo also appointed McCall Chair of SUNY’s Board of Trustees, replacing Carl Hayden. Hayden and McCall were both appointed to the board by Eliot Spitzer in 2007.

Once the announcement was made, Hayden resigned from the Board of Trustees. In his resignation letter to Cuomo, he said “My personal experience convinces me that it is rarely a good idea for a former chair to hang around.” Hayden’s resignation was effective December 31, 2011and left the board before his term was complete.

McCall also took a leading position with “The Committee to Save New York.” This is a well financed group of business executives created to promote Cuomo’s legislative platform. Ostensibly promoting economic opportunities, they have been criticized for mostly promoting corporate interests – especially lower tax rates. In effect, they are the largest lobbying group in the state.

Members include the Partnership for New York City, the Real Estate Board of New York and the Business Council of New York State. The board members of the committee and its partnered organizations include Wall Street CEO’s like Vikram Pandit of Citigroup, Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs and Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase, and real estate moguls like Rob Speyer of Tishman Speyer.

The Times reported: “Mr. Cuomo, in his remarks announcing Mr. McCall’s appointment, made only the most oblique reference to their onetime rivalry, noting that he had known Mr. McCall for many years and had been “on both sides of the table” with him.”

The article continued, “Asked how his relationship with Mr. Cuomo had improved since they opposed each other in a campaign, Mr. McCall struck a playful tone, turning to the governor and asking, ‘Did you change, or did I change?’ ”

“Both,” Mr. Cuomo replied. “I try to change every day.”

“The governor and I were never apart,” Mr. McCall added. “We were opponents, and that always happens. We’re both good Democrats.”

Mr. McCall was then asked if he could recall any single moment of reconciliation between the two of them.

“I’m not sure,” he said. “You know, there wasn’t any air to clear. I mean, we had an election, and I won.”

In the public portion of SUNY board meetings, Carl McCall remains vibrant and involved. At an age when many are retired, he is in full control, completely aware of the implications of the board’s decisions mean for LICH. He maintains that this is the only way to save SUNY Downstate Medical Center.

When acquiring LICH in 2011, SUNY promised a better run hospital. They claimed the medical school was at risk without more clinical opportunity for their students. They were also aware of LICH’s financial status, vowing to continue to operate the facility as a full-service hospital.

After ignoring the 2011 Berger Report to consolidate services into LICH and not to expand bed capacity and ambulatory service at University Hospital of Brooklyn (UHB), SUNY – under McCall’s leadership – has pillaged assets, ended a well-respected residency program and taken drastic measure to destroy LICH – against court orders. McCall has almost been successful in doing to LICH what he so strongly protested the City doing to Harlem’s Sydenham Hospital in 1976.

The SUNY system, particularly Downstate Medical School, is under extreme financial duress, as the Comptroller’s audits have shown for the last several years. While SUNY’s heavy-handed actions may be an easy fix for their budget, turning LICH into a vacant property will be disastrous for Brooklyn’s healthcare system.

It has been a long path that has transformed Carl McCall from a community organizer to a corporate operator. Leading the fight to save Sydenham Hospital, he was on the side of an underserved Harlem community that needed the help of government to keep a cherished and valuable healthcare facility alive. Thirty-six years later, he leads a state-sanctioned push to treat a cherished hospital as a piece of soulless property, worth only its real estate value.

From Sydenham to LICH, personal ambition, power and wealth seem to have trumped the public service career that once motivated Reverend H. Carl McCall.

5 Comments

amazing.

While working for the NY Mission Society in Brooklyn in the 1960’s did he becomes friends with a young aspiring John Williams (now Downstate Pres.) who was living in Crown Heights? He tried to correct apparent wrongs during Downstate’s Construction. He is now using Williams to promote the pro-black community Downstate. Williams went to college in Boston. Being a black, he had to live in Roxbury, the only black community in segregated Boston. That is H. Carl McCall grew up and still has family there. Was Williams a member of the church that the McCall were members. Church leaders helped in getting McCall into Darmouth. There has to be a connection besides the Williams, Brooklyn Hospital Pres. Richard Becker (friends for 30+ years) and Jeffrey Sachs ( Cuomo’s best friend) who represents Brooklyn Hospital. That Hospital gains if Interfaith and LICH close. Williams gains from the proceeds from their sale.

Williams was hired without a search committee.

Great story – McCall should really be ashamed of the outrageous actions he is presiding over. Total dereliction of duty. Yet ultimately, SUNY and the DOH report to Governor Cuomo. The Governor is driving these decisions, not McCall. We need to focus our energy on trying to get the Governor to change his stance, or we will end up with condos and neither LICH nor some greatly-diminished, but still useful health care institution. People are not getting the care they need and it sounds like at least one patient has already died after being forced out of LICH.

Two pieces of shit ……