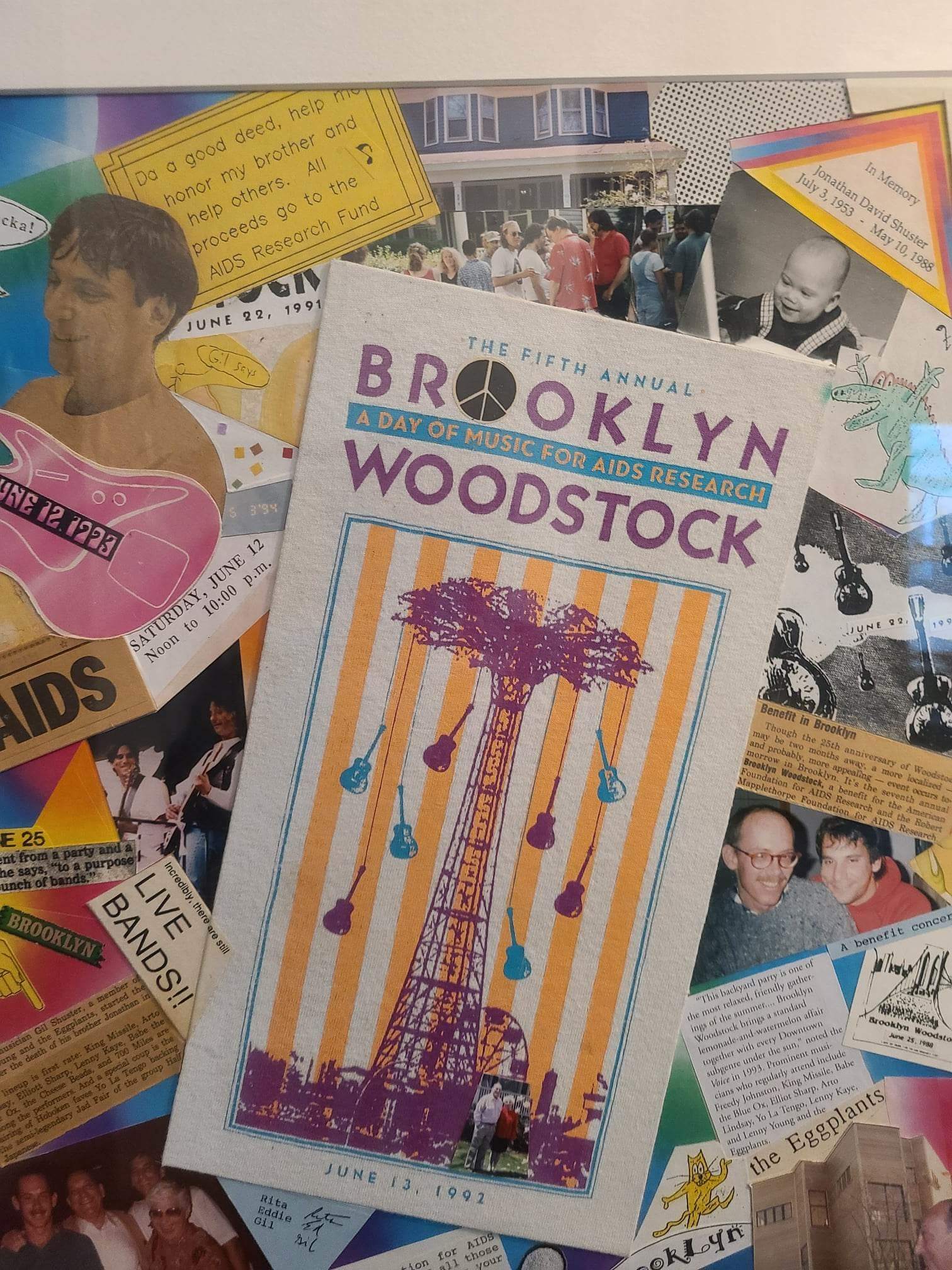

In the early 1990s, I was living in what I considered a boring neighborhood, on East 19th Street and Avenue O near Kings Highway. There were few other single people living nearby on their own, and I found little to interest me other than Highway Bagels and Adelman’s Deli. But one summer, I saw a flyer attached to a telephone pole for a one-day “Brooklyn Woodstock” mini-rock festival, also on East 19th Street but much further north, between Glenwood and Foster avenues. When the day came, I found myself walking through a neighborhood of spacious Victorian houses. As I came closer, the sound of live rock music grew louder. I entered what looked like a huge back yard and squeezed into an extremely crowded field of people siting on the grass or on lawn chairs, drinking soda, eating food and listening to a succession of indie-rock bands around 9 p.m.

Brooklyn Woodstock, conceived as a fundraiser for AIDS research, began in 1988 and continued each year until around 1994. It was publicized in the Village Voice, the New York Press and elsewhere. However, unlike its Upstate namesake, it’s largely been forgotten – partially because it was a strictly local affair, partially because it happened before the age of the internet.

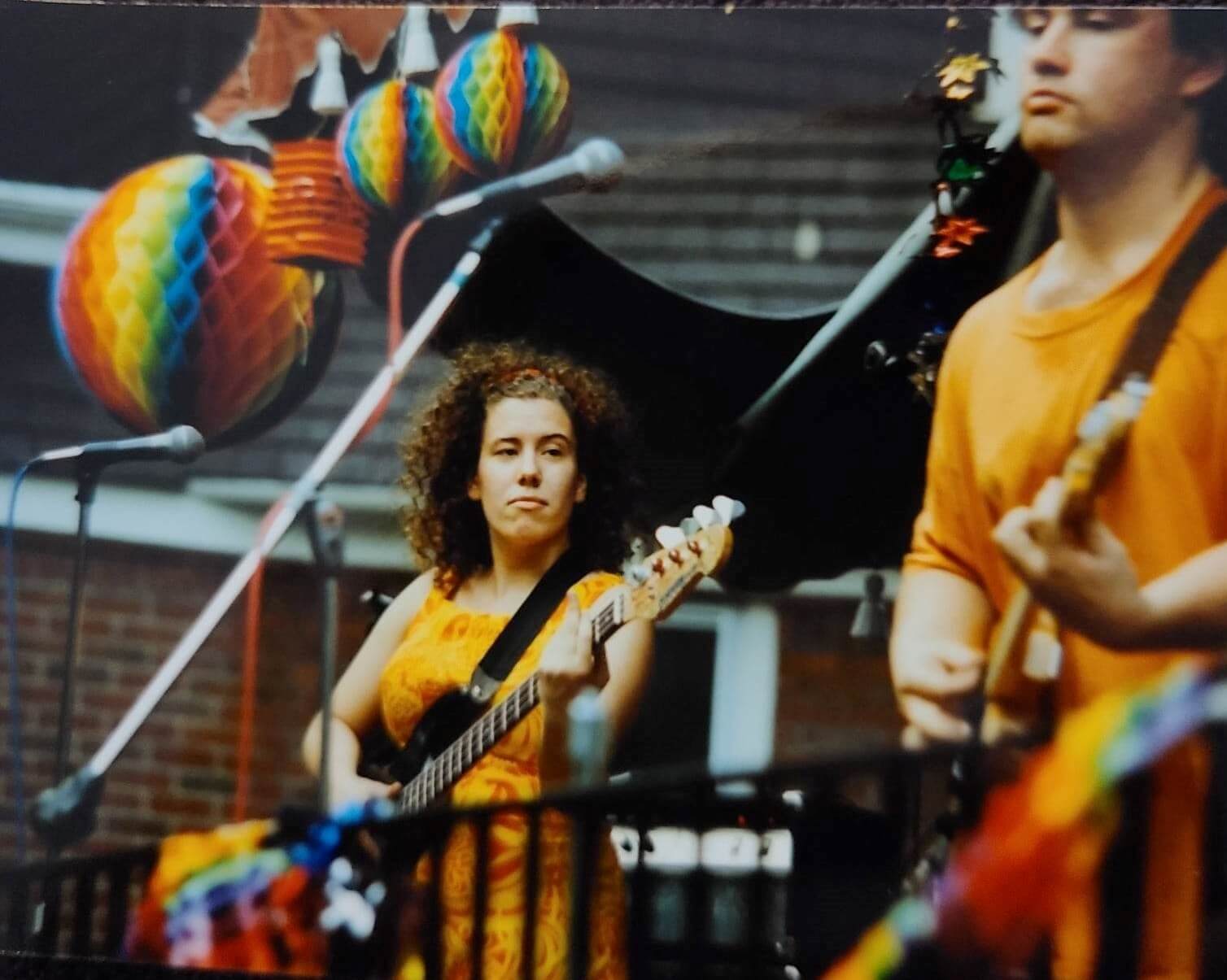

The yearly mini-festival was the brainchild of Gil Shuster, whose family lived in the house and whose brother Jonathan had died of AIDS. Shuster was the bass player CK for Kenny Young and the Eggplants, an alternative folk-rock band that performed songs like “Attack of the Manic Librarian,” “Mommy is a Lawyer” and “Savage Eggplant” and often played the legendary Windsor Terrace rock club Lauterbach’s. He also was a sound engineer for WFMU, the epicenter for New York area’s indie-rock scene in those days.

While he met some of the bands that played Brooklyn Woodstock through WFMU, he says that he encountered, and recruited, most of them at live shows he went to. “Everyone I asked said, `sure,’” he remembers.

At the time, Shuster adds, “Brooklyn wasn’t the hip, trendy place it is now, and none of the hipsters were living in Bushwick.” The East Village was the epicenter of hip, and Shuster says most of the members of the bands that played at Brooklyn Woodstock probably lived there. Indeed, most of the audience members came from Manhattan, although some definitely came from Brooklyn, including people Shuster grew up with in the borough and “everyone on the block.” When Yo La Tengo, the most popular group to play the festival, was slated to perform, suddenly 40 people or so would show up, and you knew that the subway from Manhattan had recently pulled into the station, he recalls.

George Rush, a Brooklyn musician who played bass with the Losers Lounge in the ‘90s, remembers what it was like to attend the festival.

“I went to see Brooklyn Woodstock, it might have been the summer of 1993, the year I moved to the city. I found out about it through a musician friend of mine, and I knew it was an AIDS fundraiser.

Arto Lindsay, a well-known member of the Knitting Factory scene, was playing solo, and he was kind of a big deal. Yo La Tengo was also playing when I first went out there. I lived in pre-gentrified Cobble Hill/Carroll Gardens, and when I first went out there, I said, `Where the hell is this place?’ I was in the audience star-struck, and a few years later, I was friends with some of those guys.” Rush, who now lives in Flatbush himself, also remembers that the following year. WFMU broadcast the event.

Indeed, many people who didn’t live in the neighborhood were totally unaware of Victorian Flatbush, and were surprised by its small town-like charm. “I rode my park there from Hell’s Kitchen,” recalls illustrator and cartoonist George Kendall, posting on Facebook’s Ditmas Park group. “I took Flatbush Avenue the whole way. When I finally turned off Flatbush near Gil’s place, I thought I had accidentally ended up somewhere upstate.”

Landing Yo La Tengo, which has released 17 albums since 1986 and has been called a “quintessential critics’ band,” was definitely a major coup for Shuster. Another popular group that played at Brooklyn Woodstock was King Missile, whom I saw singing their zany underground hit, ‘Detachable Penis.”

The porch is the stage

Chris Xefos of the group says that although his memory is somewhat hazy, he and another member of the group, John S. Hall, played the festival as a duo in 1990, but then may have played there with the full band, probably in 1992. “I do have a vague recollection of trying to get the full band up on the Victorian backyard porch,” he wrote in a Facebook message.

Among the other groups and artists that played the festival were Babe the Blue Ox (which later released two albums on the major label RCA); singer-songwriter Freedy Johnston; Elliot Smith, who Shuster called “a big downtown name at the time”; the band Antietam, named after the Civil War battle; and the all-female band the Aquanettas. Of course, Kenny Young and the Eggplants played, too.

Proceeds from Brooklyn Woodstock, depending on the year, went to amfAR (American Federation for AIDS Research) or New England Deaconness Hospital in Boston, where Shuster’s brother had been treated. Sometimes, the proceeds were split between the two. One year, the proceeds were split between AIDS and breast cancer research to honor Wendy Geffen, a friend of one of the bands who died fairly young as a result of breast cancer. “We didn’t make any money from the concert,” Shuster said, although he sold Brooklyn Woodstock T-shirts and there was a $10 admission. He provided watermelon, beer and soft drinks to spectators for free.

Brooklyn Woodstock probably received its greatest fame on July 5, 1990, when the Daily News published a full-page article on the festival. Several of the bands’ members said it was their favorite gig of the year. Still, the yearly outdoor festival eventually ended, with the amount of work, energy and time involved in putting it on being the deciding factors.

Today, Shuster is still a sound engineer, still lives in the house, and still performs with Kenny Young and the Eggplants. They play the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in Edinburgh, Scotland every year and have been on the BBC While in the UK, they’ve been interviewed by, and performed on BBC radio programs “a bunch of times.” “That and five dollars will get you a slice of pizza, but it’s still a thrill to be walking into the building when Jeff Beck is walking out. All in all, he says, “We’re still fighting the good fight.”

One Comment

Very interesting article!