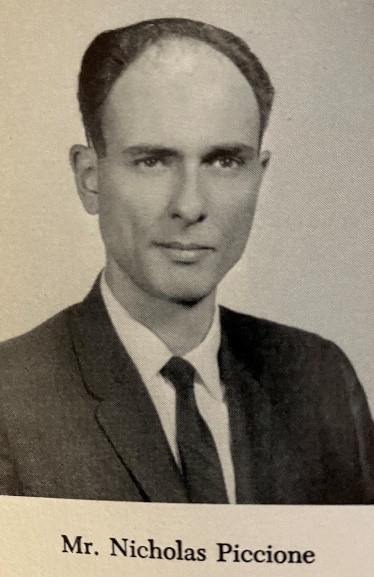

It was Junior year Physics class in St. Augustan Diocesan High School, in a Park Slope that had seen better days and would again someday but not in 1963. I had just written a novelty song about Nicholas Piccione, our math teacher, who I actually liked. The song sprang to life after I dozed off in his class while he was fishing for us to solve an equation he’d just scribbled on the blackboard:

“Z?” No! “Y?” No! “2?” No, No, No!

“N?” RIGHT!

Hearing my name, I awoke, bolted out of my seat, and answered, “Yes, Mr. Piccione!” Instead of smacking me or throwing his keys, like many of his Christian Brother and “lay” colleagues would, he smiled and said forcefully, “Wooh! Sit back down there, Enright!” Thereafter, some called me “Enny” to memorialize the whole N-Right call-and-response thing. Ha Ha. Assholes. And so to honor this kind man, I, your typical adolescent Dick-Head, wrote, “Big Bad Peach” –

with apologies, of course, to the Jimmy Dean hit record, “Big Bad John.”

Every day at the school you could see him arrive

He stood six foot five and weighed one-oh-five,

Big Peach

And so forth. Anyway, my unkind homage fell out of my Physics textbook on that October 1963 day and Charlie Duveen, sitting next to me, picked it up and started reading. He laughed and was passing it back when Brother Raymond noticed the exchange and demanded: “Step forward with that paper you are passing around!”

“But, Brother…”

“Shut up. How dare you pass this around in my class?!”

“But, Brother, I wasn’t…”

“Shut up and take your seat. I’ll deal with this when you see me in my room after school.”

Uh oh. Knowing his propensity for smacking us around, I feared the worst.

One incident, in particular, played out in my head as the minutes crawled by. It seems Brother Raymond had a thing about noise that contributed to his being universally known as “Crazy Ray.” One afternoon, energized by a lunch filled with chocolate while waiting for our teacher to arrive, we were all shouting, taunting and the like (there might even have been a few “Enny” call-and-responses). Raymond stormed in from the corridor. Instant silence. But too late.

“Gentlemen,” he began, in a voice cold as ice, “at times like this, it is best to simply take the miscreant closest to you and make an example of him.” Whereupon, he grabbed the blond kid sitting near the door by his jacket, telling him to stand, and then started smacking him with an open hand rapidly, on both sides of the face. Stunned at first, the blond put up his hands to ward off the blows and ducked away but Raymond pursued him and drove him back into his seat. He then turned to us: “No more sound? Do you understand?” The only thing missing was a German accent, a Gestapo trench coat, and a demand to “show me your papers, all of you Irish, Italian and Polish swine!”

When I went to the classroom where Crazy Ray received visitors, there was actually a line waiting outside to see him. Since misery loves company, I was somewhat relieved. Then he opened the door and the first victim disappeared inside. I listened intently for the sounds of violence (Paul Simon’s lyrics if he went to Saint Augustine). Nothing. And no red faces coming out, either. Wow, maybe he’s mellow today! As each boy left, he would whisper to the next victim to go in. Now it’s my turn. Raymond was sitting at his desk, writing something.

He looked up at me. “Yes, what do you want?”

“You told me to see you about my note, Brother.”

“Oh, that,” he said with some annoyance. “That’s out of my hands, I sent it up to Brother Jerome. Didn’t anyone tell you?”

“No, Brother.”

“Well, I’m telling you! Get out of here and see Brother Jerome,” dismissing me with a wave of his hand as he returned to his writing.

I actually thanked him as I left.

Brother Jerome, a noted pugilist, was similarly disinterested in meting out corporal punishment, thankfully. He simply handed me a sealed envelope addressed to “Mr. & Mrs. Enright,” and said, “You’re suspended. Take your books home with you since you may be gone for a good long while. And make sure your parents get the envelope or you’ll never return here.”

Wow! Free at last! On the subway home, I wondered what it would be like to be done with school. If I threw the envelope away, I would get up each morning and wander the City doing whatever I wanted. Seeing a lot of movies for sure. But then as I considered the pros and cons, I realized I was only a phone call away from being exposed.

I gave the envelope to my mother and explained what had happened. She read it and got nervous.

“They want to see us!” she said, her lips almost trembling. this was a woman who attended Mass every single day of her life. Except for Holy Saturdays, the only day of the Liturgical Year in which Mass wasn’t held because Jesus had gone toes up on Good Friday. I always thought it should be Holy Friday and Good Saturday but that idea didn’t sit well with me mum.

And so the following day, I was to stay home (yay!) while she went to meet with Brother Peter, the Principal.

“I’m not telling your father nothing so not a peep to him. As far as he’s concerned, he’d want you to be expelled and start bringing home some real money to help out.”

I had forgotten all about that. A few days after graduating grammar school, I got Working Papers so I could stand at a souvenir stand inside the Stillwell Avenue subway arcade in Coney Island for a pay envelope every week, detailing all the withholdings that my boss pocketed for herself. When September rolled around, my father said he wanted me to keep working and forget high school. “I never even finished high school, it’s not that important,” he explained thoughtfully, perhaps fighting back the anger he must have felt when his father died, forcing him to quit school and become the breadwinner at age 13. My mother overheard the conversation and overruled him, arguing it would be against the law and maybe against one of the commandments too. In rebuttal, he brought up the Fourth Commandment. “Honor Thy Father overrules THAT!” he shouted. As she shouted back, “There’s a mother in there too, you know, to be honored and such!” I slipped away.

Brother Peter was a gentler soul than Jerome and Raymond. And I’m sure my mother name-checked a lot of clergy she knew, including family members. I was reinstated and allowed to return to class. Under one condition: I had to apologize to Mr. Piccione. I would rather have been smacked by a gauntlet of the most sadistic Christian Brother motherfuckers.

I saw him after class, handed him the note, told him I was just fooling around, and never showed it to anyone, it just fell out of my…Piccione cut me off. “This is kinda funny,” he said. “Can I keep it?”

I’d like to be able to say that I was never so unkind to such a gentle soul ever again. But I’ve tried. And by the way, I learned a lot in math that year. But I failed Physics.

After I wrote this piece, I took a peek on the Interweb. Nicholas Piccione passed away in December of 2020. A Brooklyn native, he forsook a career as a mechanical engineer in the aerospace industry to become a math teacher for 30 years, first at St. Augustine, then moving on to Hasbrouck Heights High School. An online eulogy noted that after retiring, he dedicated thousands of hours as a volunteer tutor at Hudson County Community College, “assisting countless numbers of students, many of whom were new to the USA and had difficulties communicating in English.” The last line read, “He was known for his quick wit, a hearty chuckle, and his kind and compassionate spirit.” Rest in peace, Nick, and thank you.

After I wrote this piece, I took a peek on the Interweb. Nicholas Piccione passed away in December of 2020. A Brooklyn native, he forsook a career as a mechanical engineer in the aerospace industry to become a math teacher for 30 years, first at St. Augustine, then moving on to Hasbrouck Heights High School. An online eulogy noted that after retiring, he dedicated thousands of hours as a volunteer tutor at Hudson County Community College, “assisting countless numbers of students, many of whom were new to the USA and had difficulties communicating in English.” The last line read, “He was known for his quick wit, a hearty chuckle, and his kind and compassionate spirit.” Rest in peace, Nick, and thank you.