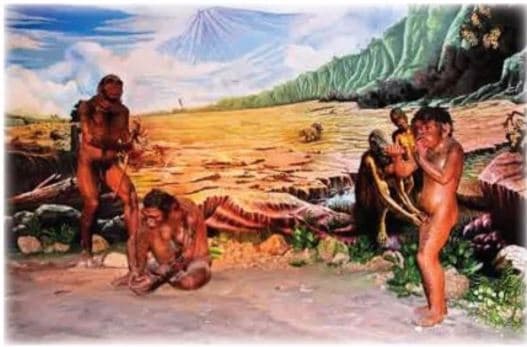

Perhaps 2 million years ago, somewhere in Africa, a hominid great ape looked down at her rough stone chopper. We’ll call her Betty.

Perhaps 2 million years ago, somewhere in Africa, a hominid great ape looked down at her rough stone chopper. We’ll call her Betty.

She was about 14 years old and was tired from watching all the children – including hers – running around. Her sisters were playing nursery, and she had time off. Already back then we assume that there was “allomothering” – allowing others to take care of one’s own children.

Using her precious free time, Betty squatted beside a tree trunk looking for termites to eat. She held a rough rock in her hand and bounced it in her palm. Instead of using it to smash termites though, she began examining the rock.

For millions of years, hominids had refined flint rocks into a tool for clobbering things and smashing food open. Betty noticed the flakes that flew off when the men knocked these cores together, and she liked them. In fact, many females had noticed that the flakes could be useful in rearing the children.

Betty collected the particularly shiny ones, the sharpest ones, and the ones that had the flattest surface. She had little piles hidden all throughout the savannah, which her troop regularly circumnavigated.

What characterized hers was sharpness. They did a great job in cutting up the meat that formed the bulk of her group’s diet.

She didn’t just find them useful – she began to covet them. Today, her little piles of things are called middens. All animals make piles of things that matter to them – most notably the food caches of corvids like crows, who can remember thousands of hidden stashes.

But this was different. For Betty there were far too many to be of use. Hers was a curated collection, among the first art collections. They were cherished as objects with addictive tactile and visual sensations. She liked fondling and admiring them.

This time, something in her brain went off when she picked up the stone core. It was too heavy and not nearly as useful as the sharp edges of her chert flakes. Maybe she could intentionally make it look like a big flake this time. Maybe she was just angry because someone had killed her mother, leaving the carcass for the vultures, and she wanted to chip, chip and keep chipping. She turned the large stone around and around.

Perhaps it was just the opposite and she wasn’t hungry at all. Perhaps she was enjoying a perfect sunny day in the savannah.

Life seemed in balance – she wasn’t scared of noises or surprises today. Survival took a back seat and she finally had the freedom to act upon her natural curiosity.

What came next is what Epicurus based his atomic theory on. He would have called her abrupt, but fecund change of habit and direction a “swerve,” a rejiggering of a formerly consistent pattern. For Epicurus it had a distinctly accidental, even random dimension to it.

The Greeks ran with the idea. If something could sharply and randomly deviate from the predictable, then humans could be said to be free from the machinations of the Gods and be willfully free to deviate as well. From the Epicurean concept of chaos comes the humanistic glory of human free will.

She wondered if she could take another rock and further chip the one in her hand, maybe she could get a really sharp and huge flake.

She happened to have a stash nearby and went to retrieve one of her favorites.

She struck the rock on her smaller rock and off flew a small chip. She picked it up, turned it over and over and noticed that one side seemed flatter. She noticed that this side seemed to imitate the look of outspread butterfly wings.

Then, she thought that if she did that to the other side, maybe it would really look like the outspread wings. And so she tried it. What she saw was a marvel to her and has become a marvel to us all.

Down the center ran a kind of longitudinal line running between the chipped edges like the body of the butterfly. Like the symmetry of her own body; like her two bilateral arms, eyes, legs, hands even nostrils. Like the feet of her children. Like everything she most liked in her life.

Most paleontologists start the record of creative endeavor around 70,000 years ago with a couple of scratches found in ochre in a South African cave called Blombos.

But when Betty decided to use the chopper to strike the flake instead, turning it around and around to decide precisely where to hit, what began to emerge was artistic – a rude facsimile of her own attributes of bilateralism and symmetry.

She had seen this hundreds of times in her reflection in the water; it had mesmerized her. She was so used to looking down in the water for this remarkable image of herself that she had become an expert at reading herself in reverse and moving her arms and body in complete counterpoint to her normal expectations.

Most of her troop never even noticed their faces looking back at them from the ripples. And today, the great apes still do not appreciate their reflections. But we do.

Maybe this was a familiarity so deeply ingrained in her smallish brain that she didn’t realize what she was copying. But there was a stealth and magnetic pull toward symmetry that dominates to this day.

No one knows if her mate or mates were watching, learning or hooting. They were all great at Simon Says because it mattered a great deal what the leaders of the troop were going to do. They didn’t seem to be able to fully anticipate behaviors of others, so they kept studying and forgetting. They made a point of studying facial expressions and movements to help anticipate things. But they never remembered. They could ape anything anyone in their extended troop of about thirty could do. It just never stuck.

No such Betty rock exists in the human paleo-logical record. There are uniface rocks like choppers but no uniface intentional bilateral flakes which we have come to know as hand axes.

This in itself is far more fascinating because what we do have are vast collections of bilateral biface hand axes. This means that very quickly, hominids turned the chert flakes around and carefully sculpted both faces, forming four equally formed wings. Perhaps what started as a swerve or whimsy not only became a fad, but a beloved and admired characteristic of humanness.

Betty’s ability to transfer into a free standing and stable design was a deep brain neural concept that mirrored her own existence and pushed forward the ascent of mankind.

Thank you, little Betty, for art took a giant leap into existence that day.