Ben Bierman lives around the corner from me, which explains how I first met him and his partner Val at the local gin palace. It was the usual Sunday afternoon gathering, and I was on the prowl for a game of cribbage, but there were no takers, no suckers, no ringers. I felt like a cross between an also-ran Paul Newman in The Hustler and a weak-kneed Steve McQueen in The Cincinnati Kid. So why not punish those unlucky enough to be seated next to me on the nearby bar stools, in this case the strangers Ben and Val? Our idle banter moved rapidly into interesting territory. I soon learned that Ben Bierman was a lifelong professional musician, and he had spent a number of years playing trumpet for the Johnny Copeland Blues Band in the 1980s. This reeked of potential for the Red Hook Star-Revue music section.

So this article is about Ben Bierman and his musical odyssey, as a player, student, author, teacher and composer, right up to the present. As Bruce Springsteen once wrote, “From small things mama, big things one day come.” My abortive cribbage foray in the pub that afternoon turned into a fortuitous encounter.

Ben Bierman is 66 years old (we are kindred spirits in the age department). He was born and grew up in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. Before it became the epicenter of hippie migration and the “beautiful people,” and long before massive gentrification transformed San Francisco into a well-heeled metropolis, the Haight was a truly mixed neighborhood, at least 50 percent black. Jazz clubs and blues bars dotted the streets and avenues. Heavy hitters like Lightning Hopkins, Charlie Musselwhite and John Lee Hooker regularly played at these joints.

Young Ben had decided that music was for him. He studied piano, learned bass in the school orchestras, and taught himself how to play the guitar. He picked up the trumpet as well. His mentor was a fellow by the name of John Coppola (RIP), a veteran of the Stan Kenton and Woody Herman orchestras. John taught him many tricks of the trade, but also instilled in Ben what some might refer to as “the code of the road.”

At age seventeen, Ben hit that road. He found himself in Chicago, performing in what he called “two beat bands.” This was the style that Guy Lombardo made famous (Louis Armstrong once stated that Guy Lombardo was his favorite musician). These kinds of two beat bands were territorial outfits, traveling a similar route as the Count Basie and Jay McShann bands in the Midwest, and Ben was part of their Chitlin’ Circuit equivalents. He even ran off and joined the circus, several of them.

At age seventeen, Ben hit that road. He found himself in Chicago, performing in what he called “two beat bands.” This was the style that Guy Lombardo made famous (Louis Armstrong once stated that Guy Lombardo was his favorite musician). These kinds of two beat bands were territorial outfits, traveling a similar route as the Count Basie and Jay McShann bands in the Midwest, and Ben was part of their Chitlin’ Circuit equivalents. He even ran off and joined the circus, several of them.

In the early 80s, Ben Bierman landed in New York City. Here he gained regular employment in the salsa, Latin jazz orbit… Johnny Pacheco, Celia Cruz, those larger-tha- life characters, along with Ray Baretto and Machito. He played all over the city, even at funerals in Chinatown. In the mid-1980s, Ben was hired by the Texas blues guitarist Johnny Copeland (RIP too) as the trumpeter in his band. Copeland was heavily influenced by the music of an earlier Texan, T-Bone Walker. Later that decade, Johnny Copeland recorded a hit blues album with Albert Collins and Robert Cray called Showdown.

Well, all of this sounded rich to me. So I asked Ben for a couple of Johnny stories. He acquiesced. On tour in some far northern snowbound Norwegian city, Johnny Copeland could not be found. The bass player and drummer were dispatched to track him down. He was discovered in a sauna. Decked out in the full black ensemble, leather jacket and cowboy boots while smoking a cheroot, Copeland calmly said, “It’s hot in here, Dick” (he called all other men “Dick”). When in Rome, do as the Romans do, not as the Texas bluesmen do.

This one is quite touching. Ben remembers an attractive woman hitting on him at a Houston gig. It transpired that she just wanted to explain to him that she was an old flame of Johnny Copeland’s, although there was more to the encounter later that evening. Johnny had set her up in the hood with a hair salon and parlor. She owed her livelihood to him, and he had never come back demanding recompense. That’s the difference between bankers and local celebrities who can afford to help their friends and who never forgot their roots. This story stuck with Ben, rightfully so.

Ben continued with his tales. He has one about how he got tinnitus (that’s hearing loss), courtesy of Stevie Ray Vaughan. It involves a massive speaker situated right behind Ben on stage. He had another one about B.B. King inviting him to play with his band at the Channel nightclub in Boston, having just heard him perform with Johnny Copeland on a National Public Radio broadcast. Ben quickly learned that B.B. would play in any key, and he called the first number in a challenging key for the trumpet, an old school play. Ben passed the audition with flying colors. Hearing Ben tell this proudly is reminiscent of the John Lennon quote, the one on the roof of Apple Studios in the Let It Be film.

Settled in Brooklyn, Ben decided to pursue the study of music. He obtained a PhD in composition, well into his mid-fifties. His research topic was George Handy, a Brooklyn pianist and composer who studied under Aaron Copeland. George Handy had a hand in progressive jazz arrangements. Ben then wrote a treatise on Pharaoh Sanders, the old John Coltrane sidekick who is still kicking. Ben was graduating from student to teacher. In 2015, he authored a book entitled Listening to Jazz. He is currently a tenured music professor at John Jay College in Manhattan.

About his life as a musical academic, Ben explains that his goal is to humanize the musicians and explain what they are trying to do and how they do it. For many of us peasants, jazz is complicated material. We might appreciate it, but we are a little lost when it comes to figuring out the hows and the whys. Ben doesn’t seek to simplify this, he wants to contribute to the discourse of why it is such a unique and important African-American cultural contribution to the world. And he wants to share his technical and historical knowledge so that others can learn too. That’s good enough.

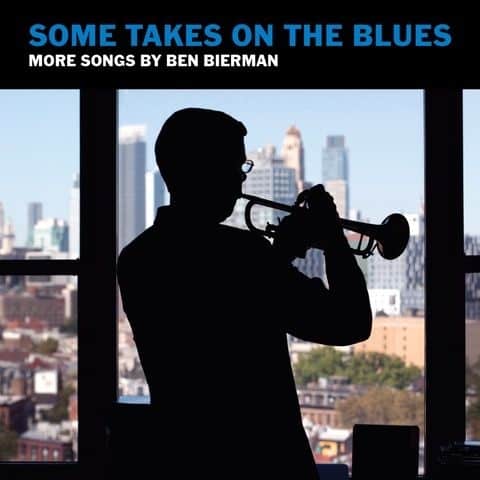

But it’s not like Ben has sacrificed the horn for the pen, or the stage for the classroom. He graciously gave me both of his latest albums, Beyond Romance (2013) and Some Takes on the Blues (2018). I want to talk these up, especially the latter, because it speaks directly to me. On Some Takes on the Blues, Ben is not only the composer, but he plays the trumpet, the piano and the guitar too, along with other guest musicians, including his son Emanuel. It is a visit into his sophisticated understanding of the music that he has been performing all of his life, delivered without pretension. I recommend these records: they belong in any serious collection. They cook.

I asked Ben about the dynamic of being the white guy in the black blues band. He replied that the only distinction that mattered to him was between those musicians who lived the life, who knew it in their bones that this was what they were born to do, versus those who might have been temporary travelers. B.B. King and Willie Dixon were mentioned here. He told me another story about a Beaumont, Texas, gig at a tinned-roof honky-tonk, where the audience was very hostile in a dangerous way. But such is the fickle nature of a drinking crowd. Their original animus eventually dissipated, and they wound up helping the band break down at the end of the set. There was no more aggro behavior, and a lot of back-slapping. There are insights here.

I asked Ben about the dynamic of being the white guy in the black blues band. He replied that the only distinction that mattered to him was between those musicians who lived the life, who knew it in their bones that this was what they were born to do, versus those who might have been temporary travelers. B.B. King and Willie Dixon were mentioned here. He told me another story about a Beaumont, Texas, gig at a tinned-roof honky-tonk, where the audience was very hostile in a dangerous way. But such is the fickle nature of a drinking crowd. Their original animus eventually dissipated, and they wound up helping the band break down at the end of the set. There was no more aggro behavior, and a lot of back-slapping. There are insights here.

Ben Bierman understands this stuff because of what he has experienced and where he grew up. His mother was a community activist in San Francisco. One of Ben’s friends was Wes Wilson, the artist who created the famous posters for Bill Graham’s Fillmore West and who recently passed away. Ben still holds some of his original prints. Wes Wilson’s next-door neighbor was the Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver. That was Ben’s world. It helped draw up the charts for the waters that he currently navigates.

I want to tell you, looking for non-existent cribbage partners has its advantages. Ben Bierman is a going concern. He deserves our full attention.

For more information on Ben Bierman and his work, visit benbierman.com.