In late 2017, at 347 Henry Street, construction began on 5 River Park, the first of four planned high-rises by developer Fortis Property Group that will soon loom over the Cobble Hill Historic District. Designed by Romines Architecture, the building’s 15 stories will hold 25 condos, with an average price of $3.15 million per unit. Work will finish on the tower sometime next year.

The ascending frame of concrete and steel beside the low-rise brownstones on Pacific and Amity streets marks the beginning of a new phase in the topographical history of the neighborhood, and in the long, painful saga that began in 2013 when, amid protests and lawsuits, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, under Governor Cuomo, decided to close Long Island College Hospital (LICH), which it had acquired less than two years earlier, in order to offload the increasingly valuable land on which it sat.

Fortis, a little-known private firm founded by a Cuomo donor, submitted the winning bid to redevelop the property in 2014.

Complicated ownership scheme

The sale agreement between SUNY and Fortis dictated a multi-part closing, whereby Fortis would make two payments of $120 million each, several years apart – an arrangement that arguably resembled an interest-free mortgage. As of 2019, SUNY – or, more precisely, its Downstate at LICH Holding Company – still technically owns a large portion of the former LICH campus: the Henry Street Building (340 Henry Street), the Polak Pavilion (363 Hicks Street), and the demolished Fuller Pavilion (70 Atlantic Avenue).

SUNY currently leases the Polak Pavilion to Fortis, which, as a condition of the sale agreement, subleases it to NYU Langone, the academic medical center affiliated with New York University, which operates a freestanding emergency department at the site as a measure to mitigate in small part the loss of LICH’s wider-ranging healthcare services.

The agreement established that, while Fortis would pay for the value of entire LICH premises (six core lots totaling roughly 200,000 square feet, plus assorted small properties in the surrounding area), the second part of the closing would transfer ownership of the 33,345-square-foot lot at the corner of Hicks and Atlantic from SUNY to NYU, at no cost to the latter, for the construction of an ambulatory care clinic.

As-of-Right prevails

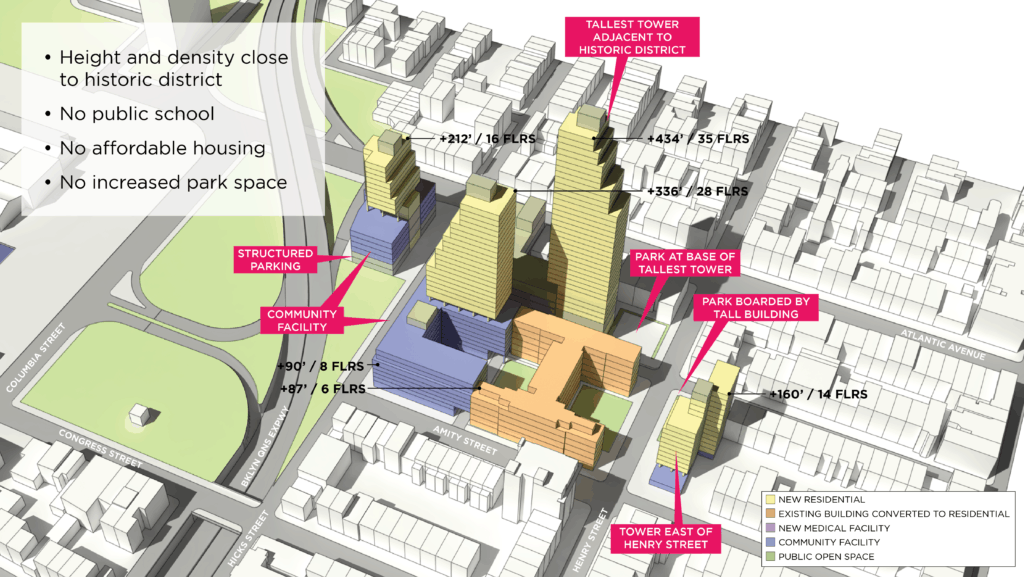

In 2015, Fortis presented Cobble Hill with two design choices for the rest of the property: a ULURP (Uniform Land Use Review Procedure) proposal and an AOR (as-of-right) plan. ULURP is the public process by which developers negotiate for land-use changes. Fortis’s proposal requested an upzoning that would have allowed for almost twice as much residential density on the LICH site in exchange for the construction of affordable housing (20 percent of the units), a public school, retail space on Hicks, and a park at 347 Henry Street. It also would have positioned the development’s tallest tower between Hicks and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE) – as far as possible from the Cobble Hill Historic District.

Following advisory review by the community board and borough president, ULURPs require a thumbs-up from the City Planning Commission, the City Council, and the mayor, while the general public weighs in along the way. (The local councilman typically has the most influential voice in the process.) On the other hand, AOR projects accommodate existing zoning regulations and require only statutory approval from the city – as long as the builder isn’t breaking any laws, they can do whatever they want, whether the neighbors or elected officials like it or not. Fortis’s AOR offered no community benefits as they needed no government sweeteners to make it happen.

Although significantly smaller than the ULURP, the AOR still includes a 470-foot skyscraper on the north side of Pacific between Henry and Hicks. Only nine buildings in all of Brooklyn are taller. This was possible because, when the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) created the Cobble Hill Historic District in 1969, representatives from LICH complained that the new zoning regulations – including a 50-foot height limit – would inhibit future growth of the hospital. The community, which had pressed for Cobble Hill’s historic designation, conceded the point and LICH was cut out of the district.

The AOR’s other key enabler, as pointed out in an article by the Municipal Art Society (MAS) last year, was a zoning lot merger (ZLM) to which Fortis, SUNY, and NYU officially agreed in an amendment – dated September, 2015 – to their 2014 sale agreement. When buildings don’t take full advantage of the FAR (floor area ratio) that their zoning permits, ZLMs give their owners a chance to sell their unused square footage to the owners of adjacent parcels.

New York City has no discretionary authority over ZLMs. “They can be done as private business deals, without public review, and the sky is literally the limit,” wrote MAS in 1999, just after ZLMs had allowed “Donald Trump to plant the world’s tallest residential tower in a midrise neighborhood” of Manhattan (where Trump World Tower now juts 861 feet into the skyline). Today, MAS advocates for a revision of the zoning code that would set “limits on the amount of development rights that could be transferred” via ZLM.

The ZLM in Cobble Hill moved 81,028 square feet of residential development rights from the site designated for NYU’s new medical facility (as well as another 34,989 from the Polak Pavilion and Henry Street Building) to a 33,108-square-foot lot owned by Fortis, thus setting the stage for a residential skyscraper as large as 210,000 square feet within a medium-density R6 zoning district. The 1969 demapping of Pacific Street between Henry and Hicks, which gave contiguity to the LICH campus and zoning adjacency to its lots on either side, facilitated the transfer.

These circumstances ensured that Fortis could make a handsome profit on its development – which it came to dub River Park – even without a zoning change, which reduced the city’s leverage during the ULURP negotiations. After Fortis’s oversized ULURP proposal met the disapproval of the Cobble Hill Association (CHA), an influential civic group in the area, and subsequent condemnation from local politicians (including state assemblywoman Jo Anne Simon, state senator Daniel Squadron, and congresswoman Nydia Velazquez) in late 2015, Fortis decided in 2016 to plow ahead with its AOR scheme. No one in the vicinity of LICH liked that plan, either.

Lander blames state

Cobble Hill’s city councilman, Brad Lander, believes that New York State had put the neighborhood into a no-win situation. “When New York State, the Governor, and SUNY Downstate decided to close and sell the hospital, they could have established provisions to make it work for the community,” he said last month. “The state owned the property. They could have decided to keep operating it as a hospital, but even if they were going to decide to close the hospital and sell it, the decent thing to do would have been to establish parameters to make it used in the best possible way.”

Lander reiterated the point: “This is a publicly owned piece of land that SUNY Downstate and Governor Cuomo decided to sell off with no urban design guidelines and no affordable housing or other public benefit requirements. I just want to be clear: that’s what got us into this mess.”

While New York State’s culpability indeed seems clear to most observers, it’s not necessarily obvious that New York City was any more determined to prevent overdevelopment at the LICH site than Cuomo was. Some Cobble Hill residents hoped in vain for a historic district overlay from the LPC for the LICH campus – a move that, if executed late in the game, likely would have provoked a lawsuit from Fortis. It didn’t happen. But more damning, perhaps, was City Hall’s refusal in 2014 and 2015 to exercise a clause in a document signed by LICH and the city on November 28, 1994, which would have reduced the size of the hospital campus property and thus the allowable square footage under Fortis’s AOR plan.

In 1994, in exchange for the right to build a parking garage on Upper Van Voorhees Park, LICH agreed to build and maintain three privately owned public spaces on Henry Street: two playgrounds for children on the west side and one sitting area on the east side. This obligation carried over to any future owner of the property.

But the Agreement and Grant of Easements also stipulated that the hospital or its successor must turn over the title to these parks to the city “if so requested in writing by the City’s Mayor, Deputy Mayor, or Commissioner of Parks and Recreation” at any point “in the period beginning August 15, 2009 and ending 20 years and 305 days from the date of this Agreement” (meaning September 28, 2015). Leaving these parks in private hands didn’t jeopardize their future as open space for public use, but it meant that their square footage continued to contribute to the total square footage on each of the lots that contained them, which in turn determined the possible square footage of the structures on those lots under zoning.

de Blasio double-dealing

As a mayoral candidate in 2013, Bill de Blasio campaigned against the closing of LICH and then, once Cobble Hill had lost the battle to prevent SUNY from selling the property, advocated that the site should remain a hospital. After his election, however, he helped broker the deal between Fortis and SUNY, and suspicions of a pay-to-play scheme earned him a federal investigation by U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara.

“I think a lot of people rightly blame de Blasio for exploiting the closing of LICH for political purposes and then proceeding to ask the bidders of the LICH site for contributions to his [Campaign for One New York] and then ultimately betraying the community that he used as the basis for his campaign,” commented Peter Bray, executive director of the Brooklyn Heights Association (BHA), the civic group representing the neighborhood that borders the north side of the LICH campus. “He is a pro-development guy. He doesn’t have it in his DNA to support community concerns about overdevelopment over the aims of the real estate community.”

In 2015, the mayor’s office publicly acknowledged its disappointment that Fortis had chosen the AOR instead of continuing to work toward a feasible ULURP. Upon taking office, de Blasio had prominently pledged to create 200,000 units of affordable housing; the Fortis development could have generated about 200 of those.

Lander recalled that he was “surprised” when Fortis chose the AOR route. “I read it in Crain’s. I sure thought they at least would have gotten back in touch with us,” he lamented. “I guess, to be fair, when they proposed doubling the density, they said, ‘This is our offer – take it or leave it.’ But that’s what they all say.”

The councilman believes, however, that, when the CHA and their elected officials rejected the ULURP, they did so in full awareness that Fortis might choose the AOR instead of creating a new proposal, and they took the gamble only because “a strong majority” (in Lander’s words) of Cobble Hill residents had deemed the AOR the better of two bad options. While both Lander and the CHA hoped that Fortis would come back to the table with “something in the middle” – that is, a ULURP with a 50 percent (or so) residential density increase over the AOR, instead of 100 percent – they were prepared to accept the consequences if the developer retreated.

“The community made that decision with a lot of information and with its eyes open. I really pushed people to be clear,” Lander recounted. “There were hundreds of people involved in the meetings and feedback and decision-making. We had hundreds of survey responses.”

Lander’s account of the Fortis negotiations is one story about what happened in Cobble Hill in the year 2015. That of Roy Sloane, who led the CHA between 1980 and 2015, is another.

Sloane’s tenure at the CHA ended when its members threatened to impeach him. He resigned instead. Sloane had deemed Fortis’s AOR plan vastly inferior to the ULURP proposal. In December, he called the AOR “just horrible. It destroys the low-scale quality and light and air and parks of our neighborhood.”

In Sloane’s recollection, “every city planner that we spoke to agreed that [the ULURP] was a better solution,” even if it would have brought “900 more people” than the AOR into the neighborhood. The most important factor, for him, was not quantity but distribution: “900 people in your living room is a problem, but if there’s 900 more people over by Brooklyn Bridge Park and fewer people in your living room, you’re better off.”

Roy Sloane’s story

Sloane disputes Lander’s history of the ULURP proposal, which Lander remembered as an offer generated independently by Fortis and received more or less concurrently by the politicians and the CHA, who then “talked and consulted” and together agreed that the plan was “too much.” According to Sloane, de Blasio, Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen, and Lander had, in fact, collaborated with Fortis to design the ULURP plan, which the city officials “overloaded” with community benefits (added to Fortis’s preexisting obligation to donate a significant chunk of the land to NYU), turning the project into a “showboat piece.”

In Sloane’s telling, Fortis tentatively consented to these burdens – the affordable housing (not yet automatically built into the ULURP by de Blasio’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing policy of 2016) and the school – only because of the hugeness of the density increase that the politicians had promised in return. By the time the plan reached the CHA, it was obvious to Sloane that the square footage was non-negotiable and that the reason it couldn’t be reduced was that the politicians wouldn’t allow a reduction in the number of community benefits, which they thought would impress the public.

In this version of events, Lander disassociated himself from the ULURP plan only after it had proved unpopular. On August 7, 2015, the Star-Revue published an account of “the first in a series of ‘Public Planning Meetings for the Long Island College Hospital Site’” and reported that Lander was “urging the zoning change process (ULURP) sought by FORTIS, calling it the best of a bad situation.” He came out against the ULURP proposal three months later, pushing for a revision that would better satisfy the neighborhood.

Ultimately, Lander may have overestimated Fortis’s commitment to the ULURP process – which, if it doesn’t work on the first try, means additional design fees and delays for the developer – while simultaneously underestimating the crypto-conservatism of Cobble Hill’s solidly Democratic homeowners: per Sloane, many of them didn’t actually care about the ULURP’s community benefits – what they cared about was the quantity of new people in the area. After all, they didn’t need affordable housing, and they sent their kids to private school.

Sloane recalled that “they said things like, ‘Oh, well, we don’t want to have a [public] school. You know what kind of kids go to those schools.’ Basically, my community turned down affordable housing, a school that was needed desperately – they didn’t want to have ‘poor people.’” Amy Breedlove, who now serves as president of the CHA, stated last month, “The community expressed in block meetings held throughout the neighborhood that they would not accept the extra square footage for so-called amenities.”

Deemed soft on Fortis by the CHA, Sloane – who, earlier in his tenure, had negotiated the parking garage deal with LICH – had been willing to work with the developer on the ULURP without demanding a size decrease: Fortis had shown to him a readiness to shift the square footage around to accommodate the community’s preferences, but none of it would ever disappear. In Sloane’s view, the CHA scapegoated him for the oversized ULURP that the city had pre-negotiated, scorning his efforts to work pragmatically within undesirable conditions.

During this period, he received angry phone calls and a rock through his window. He claimed that the regime change at CHA owed to the misguided belief of the group’s “elite lawyer-banker types” and “politicos” that they could “get a better deal.” In the end, as he put it, “they got nothing.”

Sloane’s own sources told him that, after just one meeting with the new CHA board, Fortis abandoned talks. When the developer stopped returning the CHA’s calls, its leaders must have suspected that the AOR plan was now unavoidable, Sloane pointed out.

Sloane believes that, in order to cover its tracks, the CHA subsequently embarked on a campaign to persuade the rest of the neighborhood that the ULURP proposal was worse than the AOR – even reassuring residents that the AOR, which Fortis could execute without public input, could be improved further by means of legal action (possibly an environmental lawsuit). Hoping to find a “legal silver bullet” or “unicorn solution,” the new leadership hired fresh lawyers and “consumed the entire treasury of the CHA in like six weeks.”

While Sloane recognized that his neighbors organically loathed the ULURP, he insisted that, if Cobble Hill residents had truly understood that rejecting it would mean a 15-story tower on the east side of Henry Street, they would have chosen the other route. Once completed, that tower will block the sunlight in Sloane’s backyard on Pacific Street.

An evil plan

On the other hand, Peter Bray – a relatively neutral party, as his BHA stayed out of the CHA’s Fortis negotiations – echoed the verdict of Sloane’s opponents: “I would say that the Brooklyn Heights community felt that the AOR plan was the lesser of two evils. That’s a lot different than saying that they were satisfied or pleased or happy with the outcome. It was the lesser of two evils, but it’s still an evil plan.”

With the “evil plan” now set irrevocably in motion, the CHA keeps busy by monitoring “the day-to-day stuff” (Breedlove’s phrase) on the construction site, including “things like tarps and tie-downs that have blown loose because of the wind,” parked trucks on the sidewalk, and “the lights in the superstructure at 347 Henry Street,” which have been “shining in everyone’s houses” at night.

“This is a developer who doesn’t like to answer to anybody but themselves,” Breedlove said, “so it is a daily task to keep them on track, hold them accountable, and make sure they’re doing the right thing” with regard to “safety issues and quality-of-life issues.” Last October, the Department of Buildings (DOB) issued a “partial stop work order” at 347 Henry Street after a contractor hit a gas line, and in December the DOB the ruled that the builder had failed to submit “acceptable proof” of having enacted “adequate measures to safeguard existing utilities.” As of this writing, the violation (which cost $2,500) remains active.

The backyard at 347 Henry has also turned into a battleground. Unlike the rest of the property, it falls within the Cobble Hill Historic District, which means that here Fortis must tread more carefully. When its architect proposed a brick wall on the south side of the yard, along Amity, Community Board 6 rejected the design, and the CHA requested a fence instead.

The ensuing three-part fence design – a short fence in front, followed by a wall of vegetation and then a taller fence in back – went before Landmarks on January 15. The renderings submitted by Fortis also showed various backyard features, including a pool. The CHA issued a statement condemning “any items, such as the proposed trellis, outdoor kitchen, light poles, or outdoor shower, that would be visible from the street” and “any swimming pool that would be visible from the street.”

The question of visibility from the street, which determines whether backyard features fall under the purview of the LPC, had emerged specifically because the CHA had asked for a fence instead of a wall: the fence’s sole claim to opacity, its dense shrubbery, might someday die. But the LPC formally demanded that the building’s owner permanently maintain the proposed barrier of holly, which in turn removed the issue of the historic appropriateness of the pool from its concern.

The plan earned the LPC’s approval with two additional stipulations: that the size of a brick storage shed facing the street be reduced and that the front fence be made of wrought iron instead of steel. On the problem of the unwanted pool, the CHA now puts its faith in the DOB, which, during an audit of the approved documents submitted by Romines Architecture for 347 Henry, noticed that, contrary to zoning regulations, the planned pool sits less than 100 feet back from the property line.

Romines went back to work, and in November, the DOB decided, by way of a Zoning Resolution Determination (ZRD1), that it could grant an exception for an alternate outdoor pool design that, by virtue of its positional relationship to the building’s subterranean structures, would qualify as a feature “within the footprint of the building.” Per the DOB, this pool “is proposed below the cellar roof space and as such is within the building” – thus, the “distance provisions for pools not within the building are not applicable.” Still, the issue of the pool and other kinks uncovered during the audit of 347 Henry required the developer to submit an amended set of plans for the entire building, and when the DOB examined them in January, the department found that they had not incorporated the new pool design outlined in the ZRD1 and issued a rejection.

If the CHA wants to pump the brakes on the pool, it wishes Fortis would speed up its progress elsewhere. According to Breedlove, the developer is “running way behind schedule on everything.” River Park’s Polhemus Residences and Townhouses – 17 condos within the restored Polhemus Building, an 1897 Beaux-Arts landmark on the south side of Amity, and eight adjacent rowhouses – will open this year, but the 48 condos at 1 River Park by FXCollaborative and the 103 condos at 2 River Park by Hill West Architects currently exist only as digital renderings, though workers have cleared the site for the former and begun foundation work for the latter. In September of 2017, Fortis acquired a $297 million loan from Madison Realty Capital to fund their construction.

3 River Park and 4 River Park, which will occupy the block between Hicks, Henry, Pacific, and Amity, remain more enigmatic. Since the ZLM had shifted a portion of the lot’s residential development rights to 2 River Park, Fortis considered putting a freestanding college dorm (which would count as a non-residential “community facility” in zoning terms) at 363 Hicks in 2015, but Breedlove has since heard that the building will become a private school, which will house its lower grades across the street at 350 Hicks. She expects 4 River Park to consist of a residential conversion of the Henry Street Building.

New medical facility future unclear

The largest delay, however, owes to NYU Langone, which announced in 2015 that it would spend $120 million to build a medical facility at 70 Atlantic Avenue with an expected completion date of 2018. Work has not yet started. SUNY still holds the land where NYU planned to build, although court documents show that NYU was supposed to close on the property “no later than June 30, 2016.” The lot was expected to be ready for new construction by that point.

That turned out not to be the case. Breedlove pointed to “issues in the excavation of the site. There were subterranean foundations from the old hospital and utilities… that could not be severed.” The Brooklyn Paper reported in March last year, however, that Fortis’s demolition of the Fuller Pavilion had finished, and the 2014 LICH sale agreement specified that the transfer of ownership from SUNY to NYU “shall occur on the date that is thirty (30) days after Purchaser has completed the Demolition Activities.”

Although Fortis’s promise to retain medical care at the LICH campus helped legitimize its bid in eyes of the public, the subsequent sale agreement didn’t fully guarantee a permanent medical facility. Rather, it created a set of requirements and obligations whose timely fulfillment would yield the property at Hicks and Atlantic to NYU “on the condition that it may not be used for any purpose other than the delivery of health services and activities ancillary thereto for 20 years.” In the event of a failure by NYU to live up to the terms of the bargain before the closing, SUNY would retain ownership with “the right to use the New Medical Premises for any use permitted as a community facility, not limited to medical use.”

Otherwise, upon receipt, NYU promised to provide “an Emergency Department, including not less than four (4) and as many as twelve (12) observation beds”; an ambulatory surgery center; “primary and preventive care”; “comprehensive women’s services, including perinatal care”; and “a FQHC” (federally qualified health facility). Unlike the other services, the FQHC could be located off-premises.

According to the federal government’s Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), FQHCs “are community-based health care providers that receive funds from the HRSA Health Center Program to provide primary care services in underserved areas.” The 2014 agreement noted that NYU intended to “cause the FQHC to be operated in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York,” rather than Cobble Hill. Nothing has materialized of this yet – per NYU spokesperson Lisa Greiner, “the FQHC does not need to be operational until Cobble Hill opens” – but it may still happen.

This assumes, however, that the medical clinic in Cobble Hill will happen. Thanks to the project’s missed deadlines, SUNY is no longer under any legal obligation to hand over the property to NYU, and NYU is under no obligation to receive it, but both parties may still choose to carry out the deal. “It is my understanding from recent conversations with NYU that they are still planning to move forward to build the promised medical facility,” Lander asserted.

In 2015, NYU hired architects Perkins Eastman to design its new clinic in Cobble Hill. Starting in September of that year, the DOB rejected the new building plans submitted by Perkins Eastman ten times. “It’s not uncommon for project applications for new buildings to go through several rounds of plan examinations before receiving approval,” DOB spokesperson Abigail G. Kunitz explained. “The application for 70 Atlantic Avenue was disapproved because not all the required items have been submitted to the Department.” The last failed examination, however, was in March of 2017.

Last year, in December, a new construction fence replaced the old one at 70 Atlantic, and the architectural renderings that had adorned the fence were not put back up. “NYU, as we understand it, has taken their facility back to the drawing board,” Breedlove reported.

The delay at 70 Atlantic has, in Breedlove’s words, “been extremely problematic in many ways.” In particular, it means that its eventual construction will coincide with that of 1 River Park and 2 River Park, instead of preceding it: “Now we are faced with three major construction sites on the logistically challenged block of Hicks and Atlantic Avenue, which as you know is pinned between a public park, a highway and off-ramp, a major thoroughfare, and a pedestrian easement and closed roadway.”

The CHA is working with the DOB and the Department of Transportation “to come up with the best planning and staging of these projects. Cranes, cement trucks, road closures and all that comes with it will heavily impact this block and area for 2019 and well into 2020.”

All in all, Breedlove expects another six to eight years of construction at the former LICH campus – a period that will also see a disruptive, large-scale repair in some form of the adjacent BQE, “the start of the borough-based jail at 275 Atlantic Ave.,” and possibly the building of the Brooklyn-Queens Connector, whose latest design had the streetcar running along Atlantic. “There is a meteor of major construction careening toward us!” Breedlove warned.

One Comment

And meanwhile Brad Lander is pushing the DCP plan to allow 26 Stories just a few blocks east of Cobble Hill, in Gowanus.

Isn’t it the responsibility of elected officials to see to it that zoning rights granted by “the people” actually reflect the balance of the public need for redevelopment and the need for decent livable communities–communities with real light and air?