Most New York natives and Red Hook residents are likely aware of the neighborhood’s rich industrial history and bounty of artisanal businesses, but as a five-year transplant to New York City, I had a lot to learn from the locals to find out what they think makes the area so unique and a hub for artisans to thrive.

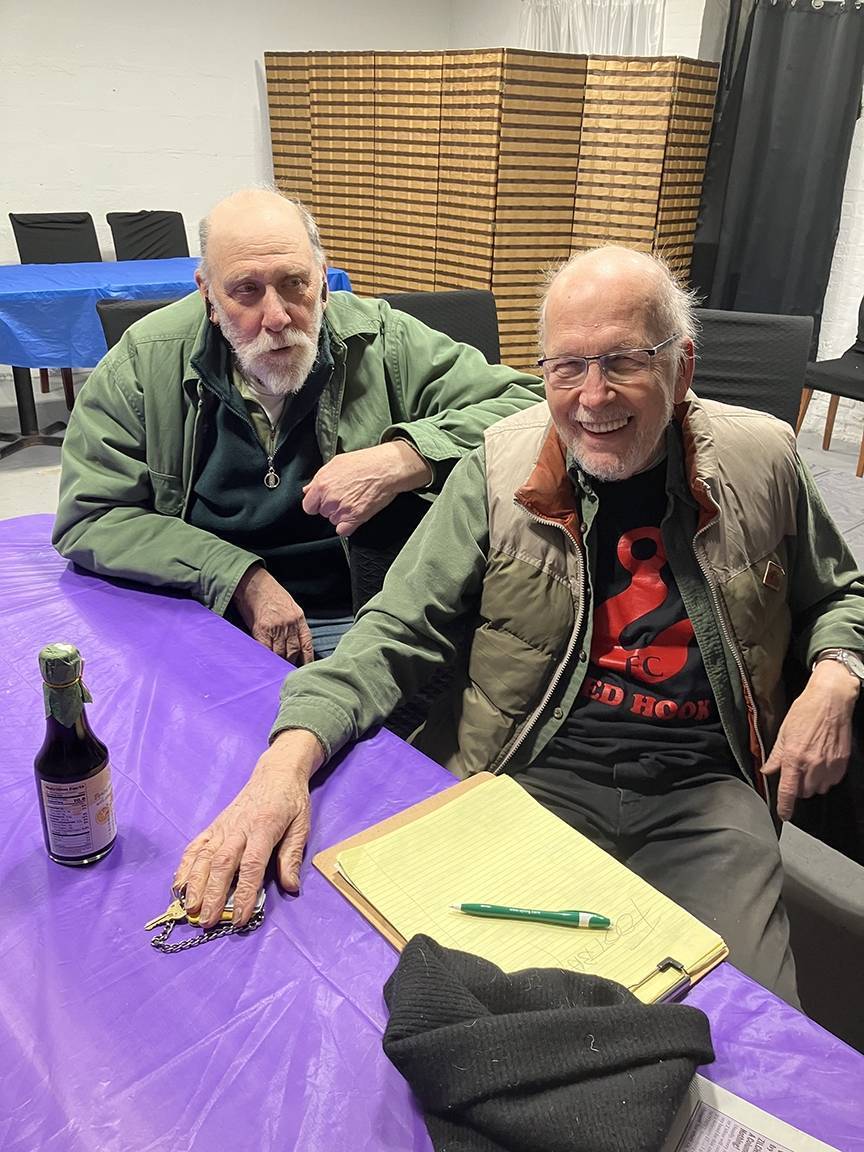

“It’s like a small village, a community of architects, designers and creatives,” Andrew Magnes, architect and founder principal of his own firm, AMA, told me.

Magnes first came to New York in 1997, eventually moving here in the early 2000’s. After working as founding partner of an architect studio, he now owns and operates his own firm. His work has been featured in Architectural Digest, Wallpaper.com, and Brownstoner. He is a big proponent of the communal aspect of his work and his partnerships with local artisans.

He was first inspired to work more collaboratively by the administrative staff at his previous firm. After their day jobs had finished, many of the admin employees were a part of an avant garde jazz scene and often performed in gigs around the city. A co-worker was in need of another musician to fill in.

Though there may be more logistical constraints in the architecture and design world, he wants to formalize the community aspect in a similar structure by working with artisans he knows and trusts to bring them work through his clients. Magnes occasionally will bring in craftspeople from within the community to take on projects he knows will work well with a client’s vision and provide quality work, working in harmony similar to musicians in a band.

A Secluded Sector of the City

Red Hook also appeals to artisans and craftspeople, not in spite of, but due to its isolated nature.

“I can focus here, not like in Manhattan,” Magnes said.

“There’s a lot of space and nooks and things of that nature. We’re able to rent and expand in a way that you can’t do if you’re smack dab in the middle of the city,” said Matthew Day Perez of Shiny Sparkle Studio, a boutique glass fusing and casting facility that he opened in 2021 with his business partner Dorie Guthrie.

Guthrie said, “Not having the train come close is kind of a special thing because people are really settled in, and there’s not this hustle and bustle that there happens to be in other neighborhoods in Brooklyn. I think that kind of allows people to hunker down, build relationships and know their neighbors.”

Though they started with a small studio space in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, they grew into a larger space last October to begin their educational side of the business, hosting classes for the general public to create glasswork.

“Looking at the scope of Brooklyn and even Manhattan, I do feel like this was a place that was affordable square footage wise, where we were able to actually expand. There’s really not many places that we would have been able to have this much of a footprint,” Guthrie said. “I love the fact that next door we have woodworkers, we have metalworkers, CNC machines, and everything kind of ends up being a one-stop shop, which is just another special aspect about being in Red Hook.”

Guthrie and Perez have been friends for 20 years, meeting at Illinois State University where they both developed their passion for glasswork. With the COVID-19 pandemic making shared studio spaces scarce, they decided it would be an opportune time to finally make the big leap and start their own independent studio. Thus, Shiny Sparkle Studio was born and is now the only facility of its kind specializing in fused and cast glass in New York.

They mostly work on B2B projects with subcontractors or architects like dining tables, sconces, or other home fixtures, but the educational side of the business, Shiny Sparkle Labs, has been a useful opportunity to introduce glasswork to the general public and to cut down on waste by utilizing scrap pieces of glass from previous client projects. It’s also an avenue for people to explore Red Hook who may not venture on the B61 bus to check out what the neighborhood has to offer.

Perez said they see about 75-100 people each weekend, most of them from outside the neighborhood.

“Generally, people are coming from the city, or New Jersey or kind of all over, so it’s nice to be in this hub,” he said.

Creating During COVID

Contrary to other industries and overall economic downturn, the architecture and design world flourished at the height of the pandemic.

From Magnes’ perspective, in 2021, “the industry was bursting at the seams.”

Construction in New York City halted for about two months at the beginning of the pandemic, but by the following year, homeowners couldn’t find designers fast enough before they were scooped up for renovations or other projects.

“Since COVID, I’ve had a lot of work, maybe more than before COVID,” Evan Yee, a metalworker at Liberty Labs Foundation said. “People were working from home a lot, and they’d spend a lot of time at home and then realize that they wanted to take on projects to make their immediate environment nicer.”

Creating pieces for clients and other projects also provided a creative outlet for artisans during a historic and isolating time.

“I found the studio a really good place to survive. Having it was honestly really nice and cathartic,” Yee said.

Guthrie had moved back to the Midwest during the pandemic, feeling uncertain about the future of her industry. However, she found such high demand in people requesting pieces like lighting, tabletops, and other pieces of art that she returned to the city.

“I went from thinking that I didn’t have a career to actually being very, very busy, so I knew it was time to come back to New York and start making work again,” she said.

Collaboration is Key

The tight-knit community and proximity to other artisans is also a key characteristic of Red Hook that helps local crafts to succeed. Perez said most of the work they are signed on for originates through word of mouth and the connections they have within their building and network overall.

Yee also cited the convenience of being close to other craftspeople in that it makes certain crafts more accessible to those who may not be able to afford it otherwise. For example, when I toured the space, he had been working on a sink base for a ceramicist that he knew.

“It’s not necessarily an accessible craft, but trying to keep it accessible in the way that we as friends who know other people who do crafts will trade and barter,” Yee explained.

Many of the artisans I spoke to ended up finding their warehouse space also through word of mouth, whether that was through an architect who already had space in a large building or from a fellow artisan who they knew before they moved to New York. Even Guthrie and her husband found their apartment in Red Hook through a mutual connection of Perez’s, since he previously had settled in the area. Most of the artisans who work here also live in the area, which makes it convenient to build connections and easier to get to work, especially when living outside of the area can be a difficult commute.

Looking Back: The Industrial History of Red Hook

During the mid-19th century, Red Hook began to establish itself as a prime location for shipping ports due to its convenient location to offload at the end of the Erie Canal. Many of these shipyards, warehouses and other similar buildings remained on the waterfront even after the height of the industrial era.

The historic Liberty Warehouse on Pier 41 dates back to the 1850s and is home to a handful of small businesses as well as work space for many artisans local to the area.

Liberty Labs Foundation supports many of these small, creative-based businesses, like woodworkers or metalworkers in their 6,000 square-foot space where its 17 members create their work and share the industrial machinery. They have been operating for about ten years, with many artists-in-residence staying at Liberty Labs for the entirety of its existence.

Yee, a metalworker and co-founder/board member at Liberty Labs, has been in Red Hook since 2015. Some of his recent projects for clients include light fixtures, stainless steel tables, metal framing for mirrors, or miscellaneous furniture pieces. In his free time, he also creates pieces to exhibit at art galleries.

He describes the history of Red Hook as similar to other former industrial areas like Chelsea or Bushwick.

“Red Hook has got a good history of industry. Artisans and craftsmen always move to more industrial areas first it seems, and now it seems like Red Hook is changing a bit more for the luxurious,” Yee said.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Red Hook

Though the seclusion of Red Hook from any major subway lines may appeal to artisans who like to hunker down and focus on their craft, prospective residents may see the lack of accessibility as a drawback. However, the views along the pier, including The Statue of Liberty, are truly unbeatable.

The appealing views and relatively undeveloped nature of the neighborhood is perhaps why the City of New York is proposing a “mixed-use neighborhood and modern maritime port” after they acquired over 120 acres of land along the waterfront of Brooklyn Marine Terminal back in May.

With the housing shortage in New York City not looking to die down any time soon, building more apartments and increasing housing supply is part of the solution. But many residents of Red Hook are concerned that the transformation of this industrial district into new developments may tarnish the historical value and charm of what makes the area so unique, especially if developers are seeking to build expensive high-rise apartment buildings along the waterfront (though city and state officials say they have no concrete plans yet for the land as of October).

“There’s part of me that sees the bright side. I hope that there’s space for multi-level income places,” Yee said.”

There’s also the potential for warehouse pricing to increase if the area develops further—with the neighborhood in its current state, many up-and-coming artists or people in need of large work spaces can find affordability in renting workshops in Red Hook, but that may not be the case if future construction projects drive up rent or decrease the supply of manufacturing spaces.

Magnes hopes to see protections in place to prevent manufacturing/industrial spaces from further turning into high-end residential or mixed-use buildings.

“To avoid being the next Williamsburg, I think we should protect zoning,” he said.

Proposed new developments are not a new concept to the Red Hook neighborhood. When the IKEA was being built, many locals opposed the construction, citing concerns including traffic congestion, decrease in property and historical value, and destruction of a number of historical structures from the Civil War era, including the Erie Basin dry dock. Despite the pushback, construction moved forward and the store opened in 2008.

Perez understands the concern but is skeptical construction of high-rise housing could develop without a reliable subway line in the area.

“Every year there’s a threat of some big developer. Like when I moved here, I was the annoying new person. I think that’s just going to happen naturally and organically,” he said. “I do think there was a really unfortunate exodus in the pandemic of all the artists living here, which created a vacuum for other people to move in. That’s where things like that would happen.”

We will see what happens in the upcoming months as the city continues to develop its vision for the waterfront, but Red Hook artisans won’t be slowing down anytime soon.

“I love that there’s a maker community in Red Hook. It’s just a really cool artist space and I hope that doesn’t change,” Yee said.