Before I moved to New York, I worked for four years as a movie theater employee. My coworkers and I made minimum wage or a little more, and many could barely afford their rent during the best of times. For some, the lack of disposable income was tolerable only because their favorite recreational activity, by far, was watching movies, and their employment entitled them to free passes not just at their own workplace but at neighboring cinemas.

New York is a destination city for cinephiles, and there’s never been a worse time to be a cinephile – or at least the kind that prioritizes the big-screen experience – than now. But for financially precarious cinema workers, whose jobs have suddenly vanished, the situation is far more dire. I talked to three employees at Film Forum, my favorite theater in the city, about their predicament during the coronavirus pandemic.

“It sucks,” Juanita Fama, a 26-year-old who joined the art-house landmark in early 2019, succinctly summarized.

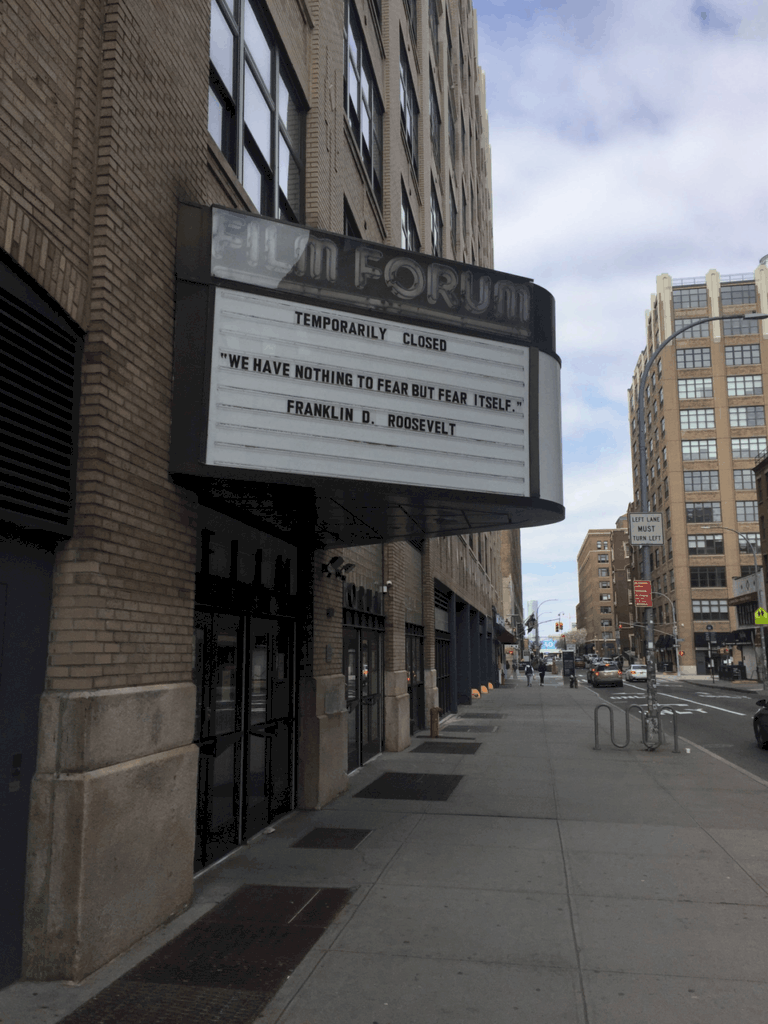

On March 12, Film Forum – an independent cinema on Houston Street in Manhattan – announced that it would limit capacity in its auditoriums to 50 percent in compliance with Governor Cuomo’s ban on large gatherings. But by March 14, management had decided to pause operations completely. Three days later, a mandate from Mayor de Blasio forced New York City’s remaining theaters to close.

Before the closure, fear had already begun to thin the crowds during what had begun as a busy month at Film Forum. “We were playing a lot of popular things, but as soon as this coronavirus thing started happening, it was a lot more dead,” remembered David Carozza, a full-time film student at Pace University and part-time worker. “It was kind of eerie. In the area in general, there were a lot less people, and Film Forum itself is kind of unique to having a large customer base of older people, the exact age range of vulnerable groups that are affected by coronavirus the most.”

Before the closure, fear had already begun to thin the crowds during what had begun as a busy month at Film Forum. “We were playing a lot of popular things, but as soon as this coronavirus thing started happening, it was a lot more dead,” remembered David Carozza, a full-time film student at Pace University and part-time worker. “It was kind of eerie. In the area in general, there were a lot less people, and Film Forum itself is kind of unique to having a large customer base of older people, the exact age range of vulnerable groups that are affected by coronavirus the most.”

Carozza moved from Connecticut to New York for college in 2016. “I come from a lower-middle-class family, and as soon as I got my own apartment, it was my own responsibility to pay the rent and pay bills,” he said.

Before the furlough, Film Forum’s paychecks had covered those expenses. “The financial situation is definitely worrying, as I think it would be for most people,” Carozza admitted.

Some help on the way

Fama noted that she’d already applied for unemployment insurance, despite some challenges on the state’s overtaxed website. “I was doing it on my phone, and it was really kind of dicey. There’d be a few hours where I’d get to one page and it wasn’t working at all. It’d be like ‘server error.’ By the end of the day, it worked.”

But, unsure when her benefits would begin to arrive, she fretted over potential delays. She had some money in her checking account, but it wouldn’t last long.

Along with Carozza, Fama had also signed up for the Cinema Worker Solidarity Fund, a GoFundMe organized by the local film guide Screen Slate and the Brooklyn-based exhibition venue Light Industry, from which she expected a $200 payout in the near future, thanks to charitable donations. 27-year-old Chris Hampson, who began working at Film Forum in the summer of 2018, had done the same.

“In terms of my own finances, I’m OK,” he said. “As soon as this happened, I immediately went out and bought a bunch of microwave food.”

Before the coronavirus hit, however, Hampson had been searching to fill a vacant room in his leased apartment. He still needs a roommate to cover a portion of the rent. “If I have to pay out that whole sum, things will get much worse for me very quickly,” he acknowledged.

For now, he’s looking to public officials for possible solutions. “My rent collects on the first of each month, so we’re nearing that date, but I have not paid any of my bills as of yet because I’m still waiting to see what the city is going to do in terms of pausing that system for the month of April,” he said. Fama mentioned that the $2,000-a-month universal basic income proposed as an emergency measure by Democratic congresswoman Maxine Waters would, for her, represent a raise, exceeding her monthly pay at Film Forum.

New York State offers 26 weeks of unemployment benefits for laid-off workers. No one knows when movie theaters will be allowed to reopen. “The problem that we’re all facing is that there is no real timeline for any of this,” Hampson remarked.

Before its closure in 2014, the Brooklyn Heights Cinema hired Hampson as an 18-year-old and taught him to project 35-millimeter film. Subsequently, in the age of primarily digital cinema, he worked as a floor staffer at Film Forum, but in December 2019, Nitehawk Prospect Park brought him abroad to help man the old-fashioned projectors that the new dine-in operation had inherited from Park Slope’s Pavilion Theater, whose shuttered moviehouse Nitehawk had bought and refurbished.

“I’d been trying to find good projection work and get out of the minimum wage bracket for, literally, years,” Hampson said. “And then this happened.”

While at Nitehawk, he had continued to pick up shifts at Film Forum to supplement his income. In a world without cinemas, Hampson doesn’t have a great deal of hope for his immediate employment prospects. “I do not have a college degree. Part of the reason I selected projection, besides being a cinema enthusiast to my bones, is just because it’s a specialized field that not many people know how to do, which creates a nice sort of job market for yourself,” he explained. “But where do you go to project movies when there are no movie theaters?”

Carozza, meanwhile, is a college senior who will soon finish his degree through remote learning. He recognized the global economic shutdown as an inopportune moment to enter the full-time labor market. “I don’t have much experience, and I’m trying to move up the ladder, and this kind of happens, and where do you even apply for a job now?” he wondered.

Long live cinema

Recently, Hollywood studios have redistributed March’s would-be blockbusters on video-on-demand and streaming platforms. Industry insiders have speculated that, even if the coronavirus is temporary, its disruption of audience habits might end standard theatrical releases for good. For Hampson, who sees 300 movies a year in theaters, this would represent a professional and personal crisis, but he noted that pessimists have forecast the death of cinema plenty of times before.

“I think that when theaters reopen, people are going to absolutely flock to them. If you go on social media right now, you have all these people who are cooped up and talking about how crazy they’re going,” he observed. “I honestly think that we don’t give audiences enough credit sometimes, and that we have this idea that they’ll simply take whatever’s easier, more convenient, less effort to absorb content and forget about it. But if that were as true as I sometimes feel that it is, Nitehawk wouldn’t have survived ten years. Metrograph wouldn’t have been able to open so recently and stay open and become a destination that people talk about who aren’t even from New York City.”

If Hampson feels relatively confident about the long-term viability of traditional cinema, he and his colleagues recognize the danger of the short-term crisis, especially for independent theaters. “They’re much more vulnerable than an AMC or something with more money behind them,” Carozza pointed out.

As a nonprofit with a host of high-profile backers like Matthew Broderick and Ethan Hawke, Film Forum may be able to count on philanthropic revenue to outlast the pandemic. It’s less clear how other small theaters, like Brooklyn’s Spectacle Theater and Syndicated BK, will pay their rent. The National Association of Theater Owners has requested a federal bailout.

“It’s also very much on the City of New York to keep the New York-y things about it open,” Hampson contended. “It’s part of the reason people still move here in droves, even though it’s absolute hell living here sometimes. I’m not saying ‘gimme, gimme, gimme’ to the city, but they need to support these sort of businesses if they want to be New York. The citizens are willing to pay for it; they simply cannot pay for it right now. So I do think it would behoove the city to provide relief to these businesses – not just to us but also to the bars and restaurants that really are part of the essential fabric of this town.”

Passing the time

To take his mind off the uncertain future, Hampson has been watching movies at home during the quarantine. Among his recent viewings, he recommends Nicholas Ray’s They Live by Night (1948) and the Wachowski sisters’ Bound (1996).

For Fama, the stress is too big a distraction. She borrowed her friend’s Criterion Channel password but hasn’t watched anything yet. “I haven’t been feeling it. I’m still kind of restless. It’s hard to read, too. It’s hard for me to feel relaxed. Maybe once the unemployment is taken care of and I know I’m not going to be completely broke, I can sink into chilling,” she speculated.

Even as the question of money looms, the “weirdest” part of the pandemic for Fama, in some sense, is the inability to go to the movies, which she had done almost “every other day” before the coronavirus. Now she goes on walks to get out of the apartment once in a while.

Carozza has used the break to catch up on schoolwork. “But even that doesn’t seem to fill a lot of time,” he sighed. “I skateboard, so I do that if it’s nice out.”

Although he recognizes the moral imperative to stay home as much as possible, he’s tempted as an artist to try to document the strange moment in New York history. “This is a very interesting time, if you take a New Wave approach, if you’re a filmmaker and the streets are empty in SoHo and Midtown – that’s been one thing that’s inspiring, almost, from a filmmaking perspective, how the appearance of the city changes,” Carozza described.

Fama looks forward to getting back to work once life has returned to normal. She, Carozza, and Hampson all expect their employers to welcome them back upon reopening. Fama misses the job, not just the paycheck.

“I really do just like working there. I’m not a person who likes work, but it’s fun. I like the people I work with, the weird people who come watch movies,” she said. “I hate talking to my roommates.”