Since Trump’s second inauguration – and the crackdowns on documented and undocumented immigrants alike that have come afterwards – growing numbers of New Yorkers are terrified to leave their homes.

Many are “very afraid to even go to work,” says Juan Carlos Pocasangre, president of Guatemaltecos in New York, an organization that has been providing help to immigrants from Guatemala since 1973. Pocasangre says that Guatemalan immigrants are consistently asking him if it’s even safe to go to the Guatemalan consulate for necessary paperwork, like renewing their passport. Although he tells them they should go but remain careful, Pocasangre says “they’re very afraid to do things.”

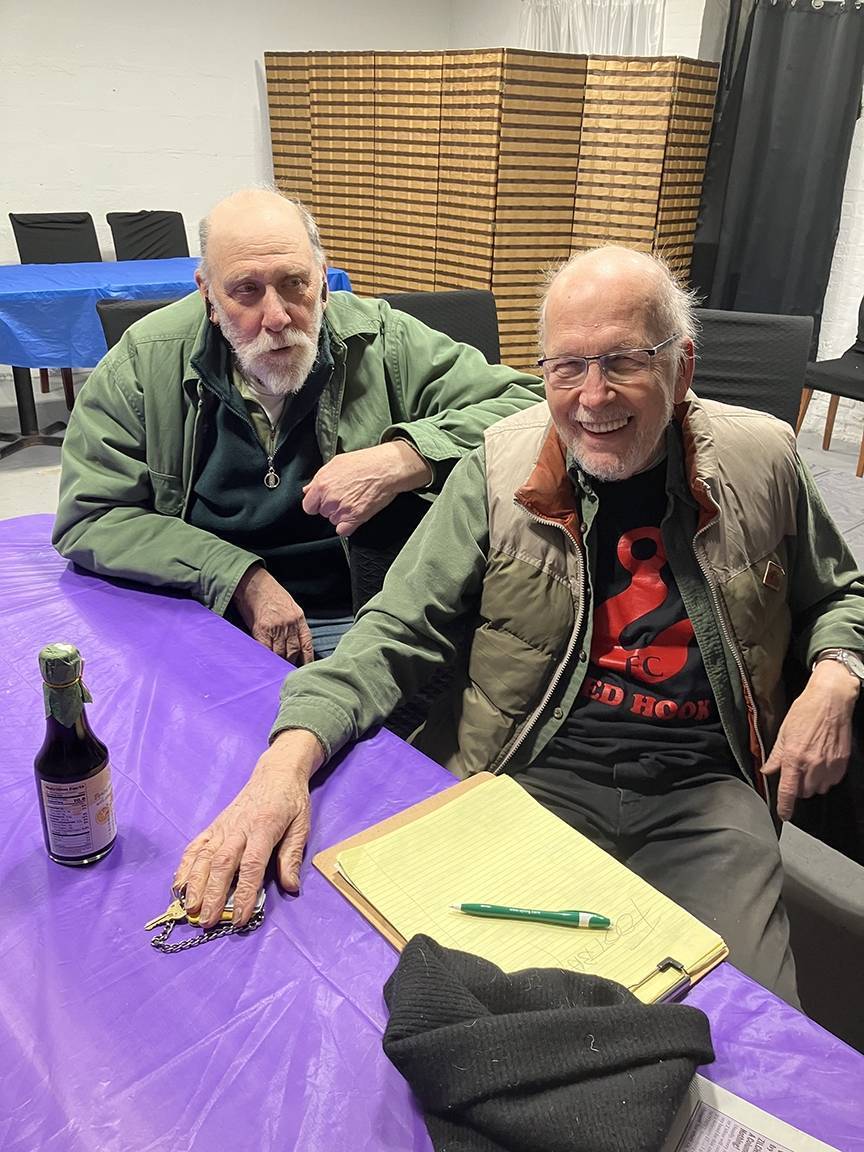

“I’ve been conducting so many workshops on how to prepare for immigration reform, how to behave in the United States of America,” Pocasangre says. He recently partnered with his friend

Lizzette Muñiz – a Personal Injury and Wills, Trusts, and Estates attorney who he calls “the best lawyer I’ve ever known” – to help Guatemalans who have been scrambling to protect against being separated from their families and children. Muniz is a Carroll Gardens resident.

Family separation threat

“They wanted to make sure that they prepared for some sort of guardianship papers – even if it’s temporary guardianship – powers of attorney, and travel permissions and travel documents for their children,” said Muñiz. Using documents from the Legal Aid Society, she put together a packet of necessary information to have in case of deportation and family separation.

“I am not an immigration attorney,” Muñiz clarified, “but I was just compelled to try to do something to help.”

Muñiz contacted the Legal Aid Society directly but did not hear back. After speaking with a private immigration attorney, she learned “the immigration attorneys are overwhelmed by calls and requests of this type, and that I probably shouldn’t expect a call back.”

“A lot of the people – even the people who are trying to figure out guardianship – are thinking about taking their kids if they get deported,” Muñiz explains. Others are opting to leave the USA with their children, “sooner rather than later. Not even waiting to be deported, because they want to save their family the trauma of the experience.”

Pocasangre gets questions from concerned residents about whether or not they should leave now, too. “Of course, I cannot tell you to go or not to go, it’s really up to you,” he says. “I just give them the pros and cons of going and not going.”

“You have no idea the stress these people go through,” adds Pocasangre. He believes that, with the information Muñiz has put together, “at least, they’re going to alleviate 90% of the stress that they have” – especially for parents with American-born minor children. With Muñiz’ packet, immigrant parents can sign an affidavit to give a relative or friend temporary guardianship for 60 days over their child(ren) in case of deportation. In the weeks after arriving back to their previous home country, parents would then need to scramble to arrange for their children to be sent to them.

“If I didn’t have documents and I had children here under 18, I would take them with me because they’re staying here by themselves,” says Pocasangre. “It’s very hectic. It’s really – it’s bad. I don’t even know how to start to tell them how difficult it is.”

Know your rights

Long before Trump’s second inauguration, the New York Immigration Coalition (NYIC) was putting on Know Your Rights workshops, which teach immigrants their constitutional rights and how to assert them.

After January 21st, “need for the workshops increased,” says Janice Northia, NYIC’s Community Engagement Manager. “Some feelings that folks were bringing to the workshop were heightened in terms of fear, anxiety, and the unknown.”

Northia knows from people who attend NYIC’s workshops that ICE has been seen walking around neighborhoods in Brooklyn since Trump’s inauguration. Some have even seen their neighbors detained. Muñiz knows someone who witnessed a checkpoint while driving from the Bronx to Manhattan. She’s read about raids on schools, churches, and job sites, about “soldiers in Park Slope pulling delivery boys off their bikes near Prospect Park.”

As a Personal Injury Attorney, she also knows medical offices in New York “have experienced a huge downturn in clients coming in to treat because the clients are afraid to leave their homes.”

“So, they’re not treating for their injuries,” Muñiz emphasizes.

Pocasangre says many use WhatsApp and Facebook to warn their neighbors about ICE sightings and to stay home, “stay quiet, and don’t open the door.”

After an ICE sighting, “don’t go outside if you don’t have to go to work, go to the supermarket and come back home,” Pocasangre says. “Please stay away from trouble. Do not get yourself in any situation that the police will come and arrest, because thatwill be the beginning of deportation.”

One of the most important things for immigrants to do, he explains, is to always carry an IDNYC – which undocumented immigrants can apply for – and to not carry ID from their birth country. “Once you show a passport or consular card,” Pocasangre explains, “you open a can of worms that is never going to end. Show your ID and keep silent.” Having an immigration lawyer’s phone number is also crucial in case one can make a phone call. Knowing one’s Individual Taxpayer Identification Number – which people without a Social Security Number use to pay taxes in the USA – is also incredibly important.

“Have two copies of those, and have it handy in case it happens. Because in some cases, I’m sure that even ICE might really respect somebody who has been paying taxes for 10 or 15 years and is not a menace to society, has no record,” Pocasangre says, explaining that in case of an ICE interaction, it’s worth contacting a family member to bring additional tax documents from home.

“This is an issue that impacts and affects every single person, regardless of your immigration status,” says Northia. As she explains, there’s a lot allies can do. “We all have the right to keep our immigration status confidential,” she says. If you’re asked whether you are a legal citizen, “you can help create a safe space for others by saying, ‘I’m choosing not to answer that question.’”

Another way to help is by participating in ICE Watch – keeping a lookout for immigration officers and letting community members know if they’re in the area – and knowing how to record ICE responsibly.

“We know from past experiences that law enforcement, when they’re being recorded, they’re more likely to follow protocol,” says Northia. Having video of ICE disobeying protocol – like not showing a judicial warrant or telling someone the motive for their detainment – can strengthen an immigrant’s chances in court.

Peter Endriss, Executive Director of Community Help in Park Slope (CHiPS), hopes the soup kitchen/food pantry’s guests “still feel comfortable to come to us.” Endriss believes CHiPS’ grab-and-go setup and accessible registration process means guests “don’t feel as exposed as they would if they were doing a complete registration and then going into a location that would be a potential for a raid.”

CHiPS has made sure its staff and volunteers know that nobody can enter their office without a judicial warrant. They also distribute Red Cards – which provide instructions for asserting one’s rights to ICE agents – and provide food for South Brooklyn Sanctuary’s weekly Know Your Rights trainings.

“In terms of immigration, all we can do at this point – and we’re happy to do it – is to just stand shoulder to shoulder with other organizations that are helping inform people,” says Endriss. “Make sure that people know their rights, so that the system that is still in place actually defends the people that it should be defending.”

“There’s a lot of propaganda that the Trump administration has put out there to divide the immigrant community into this idea people who come into this country ‘illegally’ are criminals,” says Northia. As she explains, the vast majority of immigrants detained in NYC don’t have a violent criminal history. “If we can really share that data and those stats, we can show this administration is just looking for anyone who doesn’t have legal status. And we know that not having legal status isn’t necessarily a crime.”

Northia described a recent news appearance from Tom Homan, in which the “Border Czar” was upset about immigrants knowing their rights. “The reason that he’s upset,” she explained, “is that folks are informed now about the protections that they have around their rights. So, we know that the workshops are working.”