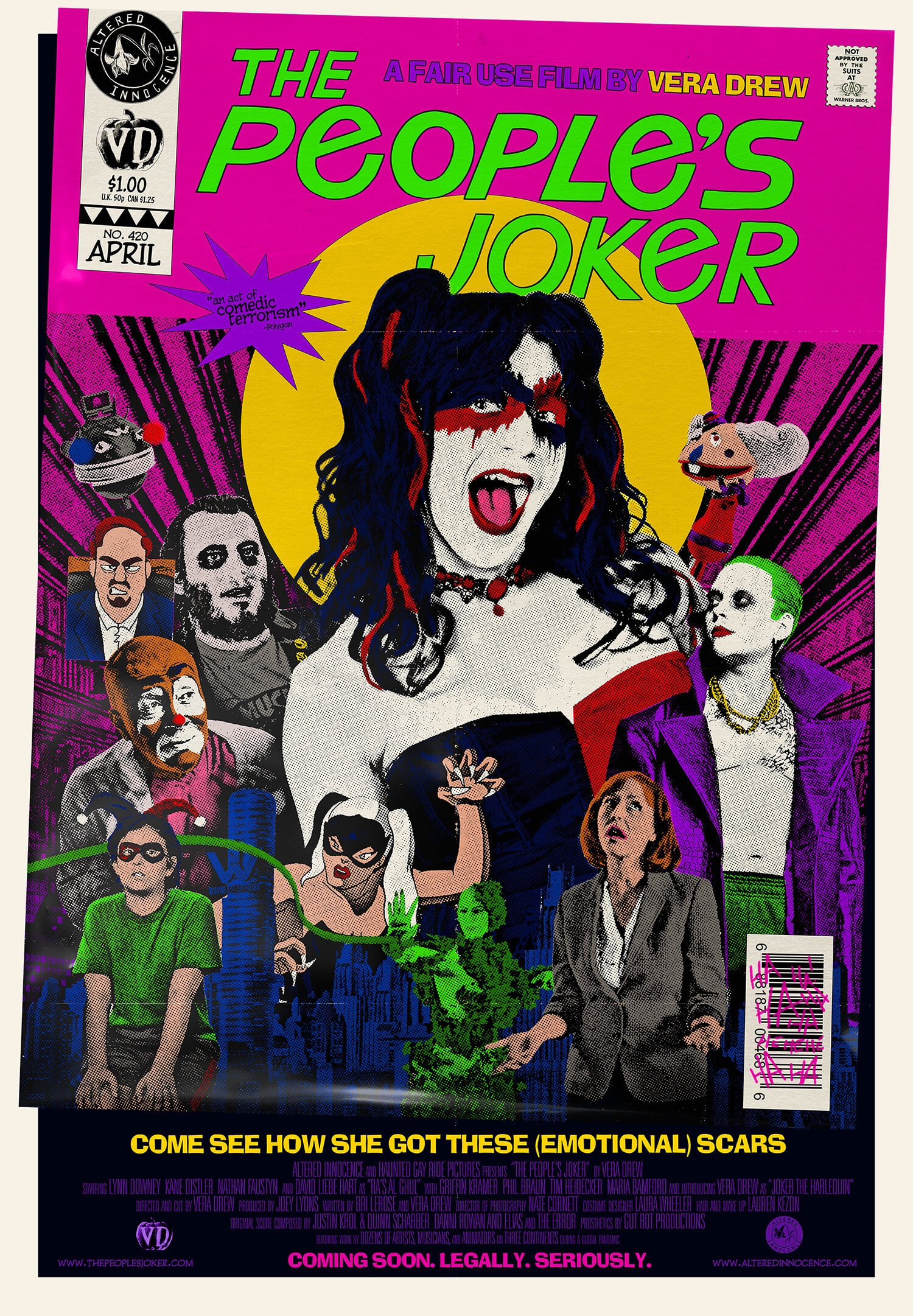

Nearly two years ago, it seemed like Vera Drew’s debut film was doomed. Not because it centered on and was made by a trans woman — a twice-over target in this era of escalating anti-trans bigotry — but because it poked a Hollywood giant.

The People’s Joker, billed as a “queer coming-of-age superhero parody,” Jokerizes Drew’s coming out experience. Its main character is a trans version of the Joker; its setting a Gotham City where Batman is a hyper-fascist groomer, comedy is outlawed, and citizens cope with hits of Smylex. Drew’s Joker the Harlequin opens an anti-comedy club in an abandoned amusement park with Penguin, drawing a rogues gallery crowd: Bane, Poison Ivy, Catwoman, Mad Hatter, Riddler, and Mr. J, a trans man styled after Jared Leto from Suicide Squad.

You can see why Warner Bros., Batman’s corporate daddy, was none too happy about the film. It sent a cease-and-desist after Drew screened The People’s Joker at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, and she ultimately pulled the film.

But that wasn’t the end. Drew mounted a fair use case for the film, arguing it didn’t run afoul of copyright because it’s a work of parody. Indeed, no one could confuse The People’s Joker — the maddest madcap Mad Magazine take on the spirit of the source material — with “official” DC product. Made on a shoestring budget, Drew shot all the scenes with her actors over five days against a green screen, then meticulously placed them into virtual environments, then tossed in animated sequences. It’s a DIY, low-fi, mixed-media fantasia as unclassifiable as it is unforgettable.

It’s also littered with riffs, tributes, and references to comic books, movies, and lore. Joker’s transition involves falling into a vat of estrogen at Ace Chemicals, a sly twist on the typical Joker origin. Mr. J, whose name nods at Batman: The Animated Series, combines the Carrie Kelley Robin from The Dark Knight Returns graphic novel, and Jason Todd, the Robin murdered in the comics by the Joker, rolled into the Leto package. Batman drives a pixelated Batmobile reminiscent of the car from Joel Schumacher’s Batman Forever, a film that changed Drew’s life. (Drew dedicates her film to Schumacher and her mother.)

The People’s Joker, which Drew co-wrote with Bri LeRose, is a singular experience of insane creativity and devotion, required viewing for anyone who grew up with Batman or Joker or who struggles with questions of identity. And, fortunately, it won’t languish on a hard drive somewhere. Ahead of a national 63-theater national run that begins at IFC Center on April 5, Drew spoke with the Star-Revue about making The People’s Joker, using the traditionally psychopathic Joker to tell her story, and the midnight-movie future of the film. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What was it about the character of the Joker that made it feel right as the conduit for this story?

I was working on something before this was ever a Joker parody. I had this idea that was like a body horror cult movie, kind of a David Cronenberg, Sam Raimi-type thing. The main character was a drag queen who was physically addicted to irony. It was this story I was trying to tell to process what it was like coming out as trans in comedy.

I’ve been doing comedy since I was 13. I didn’t know who I was for most of my life. I was completely lost. And comedy, particularly improv and sketch, was this space for me where I could explore identity and queerness in a funny way, and then in a safe way. But it also kept me locked in this stage of irony and self-deprecation. I would portray femininity in a very monstrous, aggressive way. Comedy, for me, was this playground for identity, but it was also high-concept self-harm at times. I wanted to explore that and talk about how queerness is integral to alternative comedy specifically. I really wanted to make something that was about comedy, but also about transness and finding identity.

The Joker side of it really came together when my co-writer Bri got involved. We were both really inspired in early 2020 because [Joker director] Todd Phillips was complaining about woke culture a lot in the press — as is his right. It was funny to us that the director of a movie that made a billion dollars was complaining about being silenced. Bri and I are both queer women who have been doing comedy for most of our lives. I don’t want to say it’s been hard for us because of who we are. But it kind of has. It’s a space where actually talking about having a quote-unquote “alternative lifestyle” or whatever is not really there. It’s starting to be. We’re seeing a lot more trans people in stand up and sketch and improv, and I’m so happy that’s finally happening. But the world I came up in, the world Bri came up in, wasn’t like that. So I think we just took all these themes that were going into this other thing and said, “Let’s actually make something that’s just a big, fun, colorful comic book movie that explores this stuff.” And Joker has always been a queer character to me.

How so? What was your relationship with Joker prior to making this film?

I’ve been reading comics my whole life. I particularly like the way Grant Morrison has written about Batman and Joker, that they’re toxic lovers more than anything. They’re two sides of the same coin: Batman as this vigilante agent of order, and Joker is this vigilante agent of chaos. And they can’t kill each other because they need each other. And in Frank Miller’s portrayal, in The Dark Knight Returns, Joker is closer to David Bowie. We’ve never seen Joker explored in that way in a cinematic space. And to me that was the thing that was the fair use parody critique that we could bring to it. Like, let’s actually talk about representation and not in an annoying way. Let’s talk about it in a practical way of how a character like the Joker could be related to the experience of a trans woman.

Todd Phillips’ Joker was inspiring to me. It was a comic book movie about a mentally ill person who the system is failing, his family system is failing him. Everything is collapsing around him and he just wants to make people laugh and be himself, and he can’t even do that. People are exploiting him… I related to that so much as a trans woman and as a comedian. We really wanted to amplify those things. And thinking about the Joker as a mythic figure and the trickster archetype and the jester and all that stuff, in the context of queerness and magick, was very much part of it, too. I don’t know, I needed to mythologize my life to sort of understand it.

Is that why there are two Joker figures in the film? I know that the character of Mr. J is not technically Joker, but he is very indebted in his look and attitude to Jared Leto from Suicide Squad.

I genuinely love Jared Leto Joker, first and foremost. Suicide Squad 2016 is probably my favorite modern comic book movie just because it’s so crazy. And its portrayal of Joker is kind of this weird raver gangster vibe in scummy Hot Topic. It’s a version of Joker I had always wanted to see, quite frankly. So that was the kernel of inspiration. The character of Mr. J in this film is based on an actual relationship I had with a comedian. We were very toxic together, and he was very abusive and [terrible]. So it made sense to make him Jared Leto Joker.

One of the first ideas we had at the script level was the first line in the movie: “From as far back as I could remember, I always wanted to be a Joker,” this idea of a Joker in this reality being a career you could have. It’s a part of their economic capitalist hellscape. So l think it kind of was, like, let’s take this sort of iconic portrayal of the Joker and put a parody, fair use commentary spin on it by casting a trans man, Kane Distler. The idea of having a Jared Leto Joker with top surgery scars, I love it. That’s the stuff in the movie that just got me so excited. And having him as a sort of composite next to Joker the Harlequin, the Joker I’m playing, was there to demonstrate that I was making a new version of this character. Having both of them demonstrates that my Joker in the movie is a new version that you’ve never seen before and is only a Joker that I could make.

That’s true for the look of the film, too. There really isn’t anything that has the aesthetic of The People’s Joker.

Necessity is the mother of invention. Writing it, we’d reach a point every five pages or so where Bri and I would turn to each other and go, “I don’t know how we’re going to do this. We just wrote a sequence where two characters are breaking up while a Batmobile is chasing them. And then they crash into a river and it descends into a whole big final showdown between our parody Batman and all of our parody Batman villains.” The process of writing the script was just, “Let’s not worry about that yet. Let’s just write the story we want to write.” It’s definitely a different type of comic book movie than we’ve seen before, but it really leans into that big sort of epic storytelling and broadness.

I came up in post-production. I’m a visual effects artist and animator. So I kind of just gave myself permission for the movie to be very low-fi and mixed media. I think Natural Born Killers is one of the biggest guiding lights for this movie, besides Joel Schumacher stuff, in that kind of every single shot has a different aesthetic. I really wanted to hover around that idea, and thankfully I was able to pull together a team of incredible artists. The movie really started as a big kind of DIY community art project, and that was always the guiding spirit.

Finding the aesthetic was very gradual. We had written it to kind of be set in these parody versions of set pieces and locations we’ve seen in other superhero movies. But it was really just a process of leaning into the fact that, OK, it’s going to be a lot of different styles. And I think it works because the movie itself is about searching for your aesthetic and searching for the solid version of your identity and trying to grasp it.

How freeing was it to write a script without any kind of physical or even temporal realities?

It’s the only way I want to write now. It was very freeing at a script stage. But then the second the script was done, it was like, “OK, I need to storyboard this entire thing.” I made an entire animatic [moving storyboard] version of the movie. And I did that because it’s not as simple as just placing an actor in front of a green screen and saying, “We’ll figure out the background later.” The reason the movie works aesthetically is because we really dialed in the lighting and the looks before ever getting to set. I knew generally what every single frame was going to look like. Again, a lot of our reference points were like… There’s a scene where Joker and Penguin are talking in this alley, and it’s a recreation of an alley from Batman Forever. We recreated the brick walls, we knew where the light would hit them.

So when you’re writing, did you place specific references, like, “Exterior. Batman Forever alley. Night”?

Yeah, I think we did. There were so many versions of the script, and the version that we used on set, pretty much every single actor told me it was kind of unreadable. Nate Faustyn, who plays Penguin, was like, “This is like a crazy person’s idea of a script.” It was written exactly like you said, it had all those reference points in it. And I did that because I also really thought of it, at least in the beginning, like segments, just because of how collaborative the project was.

I had a small army of people helping me make this. I announced I was making the movie May of 2020 on a podcast I used to have, and hundreds of people came out of the woodwork saying, “I want to watch this movie, and I will help you make it.” Most of those people really don’t have aspirations of working in film or TV. They’re visual artists. So it kind of was necessary to have this very non-traditional script. It was like a weird, big, long magic ritual with ingredients rather than a proper screenplay. But that was also the best way to convey what we were picturing. It’s exactly the movie I want it to be. And I’m so happy with it. But it definitely looks a lot different than I thought it would, and it looks that way because of that script.

You dedicate The People’s Joker, in part, to Joel Schumacher and you’re explicit about how Batman Forever changed your life. How do you ensure your film stays in front of people so someday somebody makes their own movie and dedicates it to you for having changed their life?

That just sent a chill up my spine… I don’t know. Honestly, one of the craziest parts of this experience has been seeing how much this movie already means to people, having had the experience of taking it out to festivals. [There were people who didn’t want me to do that.] But my whole thing was: There are hundreds — and I know it’s not that much compared to the amount of people that could see a movie — but there are so many trans people that are excited about this coming out, who haven’t seen a frame of it and know it’s going to mean a lot to them. I needed to bring this to festivals. And the idea of having all my stoner and shut-in fans be forced to go to a theater to go see this movie was really cool.

Having the experience of screening it, I really got to see firsthand, like, wow, this movie really is emotionally effective. Trans people, anybody who has a complicated relationship with their family, anybody who makes art, anybody who feels left behind by the American dream — I think they can relate to it. That all has been so cool. And very humbling. And very intense. I was not prepared for my first movie to have this level of exposure or for it to mean this much to people.

But because of that, I don’t know that our theatrical run is ever going to end. I see this as a midnight movie. It’s a low-fi movie, but it’s got a wide scope. It’s a movie that’s meant to be a communal experience and viewed in theaters on a big screen with your chosen family.