Is it too early to say there won’t be a 2022 Major League Baseball season? Because it sure feels like there won’t be one. If the current lockout, which has already claimed some of Spring Training, begins eating regular season games, which seems likely, who knows where things end — or how the shrinking fan base will react.

But maybe baseball is doomed anyway. Cultish devotion to advanced metrics has made watching games miserable. Call it the zombieball era. Hard-throwing pitchers have turned baseball into a sport of strikeouts. Hitters clad in body armor look kitted out for war, not an at-bat. Data-driven managers cycle through endless middle relievers, sometimes one per batter, and innumerable infield shifts. So don’t even think about stolen bases — you’re not getting on base. And all those unwritten rules turn players into dour sourpusses and joyless robots. (It’s not for nothing that Bryce Harper, in 2016, started the (unsuccessful) Make Baseball Fun Again campaign.)

No wonder the only people actively interested in baseball are old timers, stats nerds, and stubborn dummies like me.

Baseball has always been a bit conservative; nothing so old could escape that fate. But it never used to be this way. The pre-steroid era had a shaggy, hangdog quality, less hyperprofessional, more accessible. More human. Players didn’t physically resemble comic book characters and going to games didn’t feel like attending a corporate retreat. Baseball was fun. And often weird. And, sure, frustrating in its traditions. But it was always thrilling to enter a stadium and be awed by the spectacle and pageantry of baseball.

That’s one reason why it’s such a favorite of the movies. Other sports are more cinematic, but none are a better match for the silver (or streaming) screen. The individual storylines embedded on each team, in every inning, during every at-bat make it rich in storytelling potential. And it’s America’s Pastime. When we see a baseball movie, we bring to it our unique history with the game and the nation, projecting ourselves, our anxieties, our dreams onto the film.

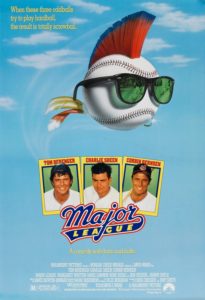

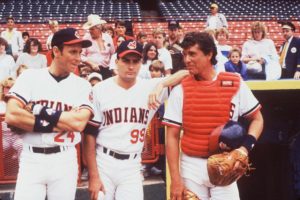

The baseball cinema canon is rich, but with the current state of the game — and the current owner-caused labor trouble — Major League feels particularly appropriate. David S. Ward’s 1989 worst-to-first R-rated comedy about the hapless Cleveland Indians and its insidious owner’s designs to move the team to Miami by fielding a squad so bad no one wants to attend games, was a hit when it was released that spring. It grossed nearly $50 million (on an $11 million budget), spawned two sequels, launched Wesley Snipes’ career, and confirmed Charlie Sheen’s movie star bonafides. (Major League also stars Tom Berenger and Corbin Bernsen, along with a solid cast of character actors, like Dennis Haysbert and Chelcie Ross. It’s James Gammon, though, as manager Lou Brown, who steals the show. With his wheezing-engine voice, push broom mustache, and endearingly gruff demeanor, Gammon is, hands down, the best manager in baseball movie history.)

Some of the film has aged poorly, particularly the inane romantic subplot that finds Berenger’s Jake Taylor borderline stalking his ex, played by Rene Russo. If you squinted hard enough in ‘89, it might have seemed endearing; in our #MeToo era, it renders our ostensible hero a pathological lowlife. And then there’s “Indians” and the team’s racist logo, both of which Cleveland jettisoned for Guardians starting in the 2022 season. But most of Major League holds up: the well-timed gags and jokes land, the achingly predictable narrative arc still connects, broadcaster Bob Uecker is still incorrigibly fantastic. (“Just a bit outside” remains a killer laugh line.) And at a crisp 107 minutes, the film is zippy and pleasantly efficient.

What helps is writer-director Ward’s macro view. He fills the frame with Cleveland, the city and its people acting as a kind of Greek chorus commenting on the team’s fortunes. The film opens with a three-minute credit sequence, a time capsule of a late-‘80s hard-luck Rust Belt town set to Randy Newman’s “Burn On;” a recurring series of locals pop up to vulgarly rag on the club then jump on the bandwagon. It’s hard to imagine a film taking such detours in our present era of short-attention-span kinetic filmmaking — then again, it’s hard to imagine that this kind of film would even get made today. Major League is the type of mid-budget picture Hollywood has abandoned. That’s a shame, for lots of reasons, but perhaps most important is that it robs us of low-stakes, up-tempo escapism that’s both bright and celebratory. Every atom of Major League is out of vogue today, and returning to it feels like visiting an oasis.

That goes for its presentation of the game, too. Is it the best baseball movie ever made? Nope. Characters are as two-dimensional as baseball cards. The Yankees, Cleveland’s big bad nemesis, is more Gas-House Gorillas from “Baseball Bugs” than an actual ball club. And it often feels like it’s chasing the ghost of Bull Durham, Ron Shelton’s much better film released a year earlier. (The Berenger-Russo plotline, especially, comes off as a thin-gruel version of Durham’s Kevin Costner-Susan Sarandon relationship.) But it resonates, still, because it’s a time machine back to a not-so-long-ago era of the game. Players — on every team, not just Cleveland’s squad of misfits — range from fit and lithe to broken and doughy. (Not a bulging roid freak in the bunch.) Batting helmets are hitters’ only armor. Pitchers routinely make it into the ninth inning, even after they give up two-run shots in a big game. Guys who throw 96 mph fastballs, like Sheen’s Ricky “Wild Thing” Vaughn, are seen as freakish specimens, not just another dude trying to make the rotation. And players perform elaborate clubhouse superstitions, show emotion after a big hit (without fear of reprisal), and — gasp! — have fun. Have mercy.

Some of this is narratively convenient Hollywood pablum, sure, but it’s easy to buy into the thing when it’s so enjoyable to watch. Doubly so when you realize something like this will never exist again. Try to imagine what a Major League made for this moment in baseball history would look like… Actually, don’t; it’s too depressing.

What Major League — and the baseball picture generally — shows us is that the game is at its best when it’s exuberant, slightly crass, and always unpredictable. (Ironic for a genre that leans so heavily on formula.) Last-chance guys with busted knees, fireballers just out of prison, and walk-ons with more confidence than skill, assembled as dead-end losers, can, with the right down and dirty leadership, put together a winner. Every fan of every basement dweller, deep down, looks at the Opening Day roster and imagines a Major League-like miracle blessing their team. That hope sits at the center of baseball, and it’s what data robs from the sport. If there’s no uncertainty, if everything is predestined by the advanced stats and metrics, why even play the games? And how do you tell stories about a sport built on myth that has been stripped of its mystique? A film like Major League endures because it bottles the essence of what’s best about baseball. That’s a precious thing when not even baseball seems to know what’s precious about baseball these days.

That said, this isn’t strictly a nostalgia trip. I chose Major League as my baseball fix because it’s explicitly pro-labor. Or, put another way, it’s a one-hour-and-47-minute-long middle finger to management. Besides being a gold-digging creep, team owner Rachel Phelps (Margaret Whitton) — by disinvesting in the Indians in every conceivable way — is an avatar for the venal culture of profit primacy that, more than 30 years later, has rotted major league baseball to its core. In any given season, only a handful of teams are actually competitive; every other club is just an exercise in revenue extraction for cheapskate owners more interested in lining their pockets than investing in their squads. And Phelps points to the future, again, with her plan to tank the season to achieve her goal of moving the team to Florida. Taking a dive is officially a no-no, but it has become a kind of tacitly accepted strategy not just in baseball but across sports — owners’ middle finger to fans.

Player-owner tension is in sports movies’ DNA, but Phelps is clearly the bad guy in Major League. And at a moment when actual baseball owners are willing to tank a season to pry a few extra dollars away from players, she’s a good stand-in for members of that uniquely American class of oligarchy acting as actual villains of actual baseball.

Watching Major League in 2022 is bittersweet for both movie and baseball fans. You’re left wishing for more films of this scale, and it’s a reminder of what the sport used to be. Made a few years before baseball’s last major work stoppage in 1994-95, it captures a period that’s hardly aspirational but certainly more fun. How could anyone see this kind of baseball and think, “Yeah, watching a quant-nerd simulation run on real people in a big stadium sounds like a great way to spend five hours of my life”? (I wish that were a rhetorical question.)

Maybe the lockout will surprise everyone and result in a better deal for players and a better game for fans. Hope springs eternal — the creed of every true-blue baseball fan! But if we’re not going to have the real thing in 2022, the movies give us plenty of ways to enjoy an idealized version of the game. And you could do a lot worse than Major League.