Any New Yorker who glances at the local newspapers knows something of the major inconveniences and outright horrors experienced by residents of the misgoverned and cash-strapped New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) in recent years, but sometimes a visual aid helps. It’s one thing to read about a corroded pipe bursting; seeing the veritable waterfall gush – nonstop, for hours – into the lobby of a building where people are meant to live is another.

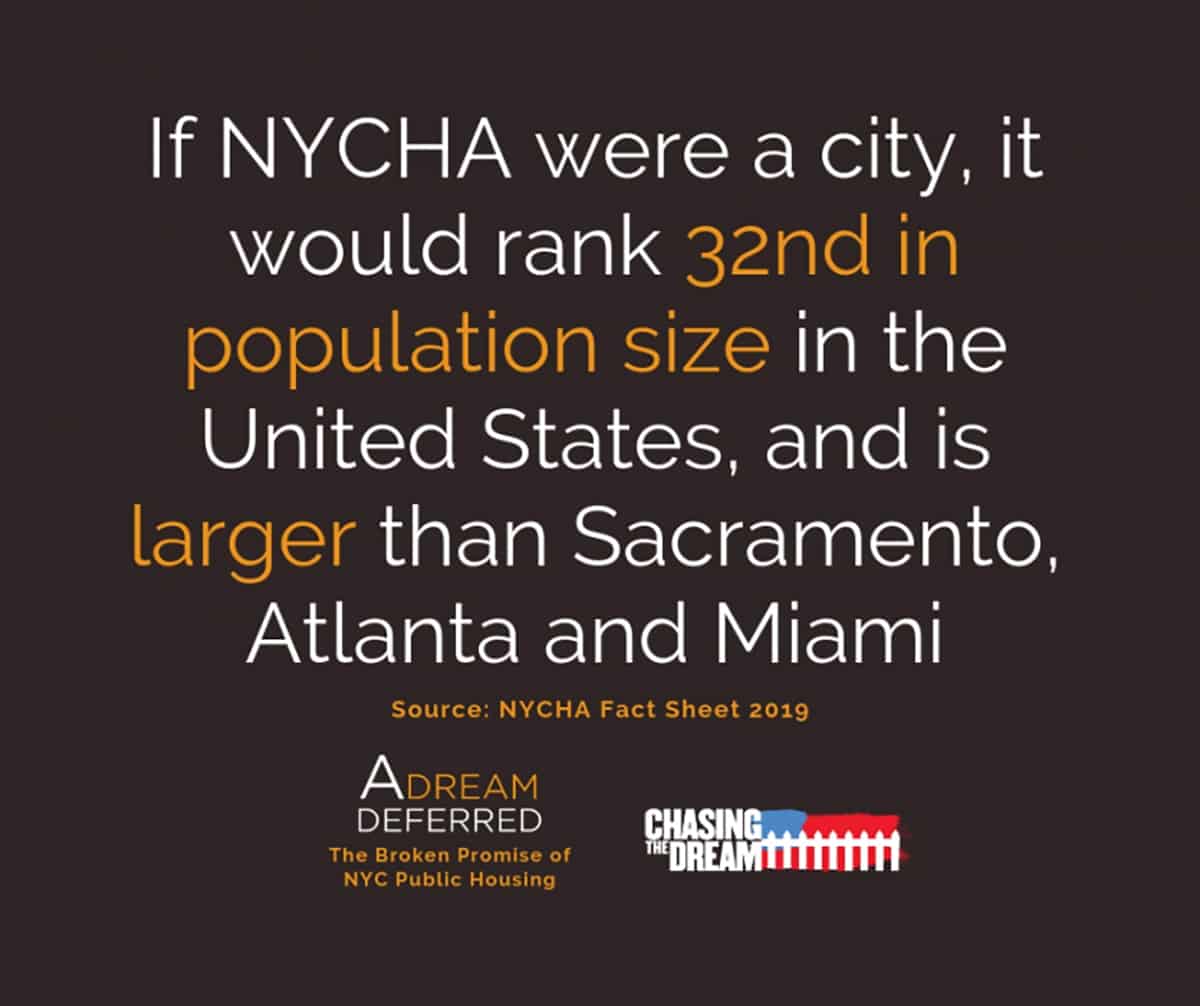

Over the summer, New York City’s PBS affiliate, WNET (aka THIRTEEN), released A Dream Deferred: The Broken Promise of New York City Public Housing, a “digital docuseries” following a handful of NYCHA tenants in Brownsville’s Seth Low Houses through everyday trials and administrative upheaval. Akisa Omulepo directed the five short episodes, now streaming online, as part of WNET’s larger project “Chasing the Dream,” which explores “poverty, jobs, and economic opportunity in America” through video content.

A Dream Deferred reminds viewers that public housing was not always an American tragedy. It began under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal as the product of an optimistic, activist government, based on the notion that every citizen should and could have a decent place to live – a promise in which public officials have since seemed to have lost faith.

“When I came here, it was beautiful. I loved it,” remembers Sylvia Arrington. Now, when Shelevya Pearson leads a cameraperson up her building’s stairwell, she encounters used condoms and feces on the steps. Inside the units, duct tape covers rotted spots in the walls; a broken kitchen sink may sit on the floor, or a single hot plate may stand in for a stove. Pearson struggles to treat her daughter’s asthma, brought on by moldy walls when she was a premature infant.

Percival Grant, a maintenance staffer, does his best, but he has 1,000 apartments to look after. He’s not a plumber, but NYCHA frequently dispatches him for jobs that require one. Yvonne Davis points out that, in the old days, when the repairman visited her to fix one thing, she might point out another minor problem, and he’d gladly perform the fix impromptu: “Everything didn’t require a work order.”

The situation shows how, when resources fall short, an insurmountable backlog of jobs produces additional layers of irritating bureaucracy – in the form of box tickers and flak catchers – as a means to create breathing room for an overwhelmed administration. Davis knows she deserves better: “We follow the rules. We pay the rent. So I don’t think I have to beg and plead to get the services that I’m duly entitled to.”

Still, some residents have picked up their landlord’s slack. Davis’s husband has fashioned a plastic exterior window covering to reduce leakage on rainy days, which once left large puddles on their floor, but the makeshift solution means no fresh air or natural light for their apartment.

Meanwhile, Arrington, sick of the neglected landscape outside her building, has started gardening. “I spent money buying rose trees and every kind of flower out there. I’ve had people tell me, ‘The reason we come this way to go to work is to admire your flowers.’ It’s just my idea of the way I want to live. I want to be part of something beautiful,” she says.

Last year, when NYCHA settled a lawsuit after its lead paint scandal and agreed to federal oversight, Trump-appointed HUD regional manager Lynne Patton visited Seth Low for a public meeting and press conference. As a condition of the settlement, New York City agreed to spend an additional $1 billion on the state public-benefit corporation, but by its own estimate, NYCHA needs an infusion of $32 billion in capital funds to remediate its properties adequately.

At the press conference, Garnette Gibson stands up to complain that, when a broken wastewater line flooded her mother’s apartment the day before, NYCHA workers were too busy prettifying the courtyard’s shrubbery in advance of Patton’s visit to help. Later, as the media departs, another resident shrugs at the whole production. “It wasn’t done for the residents. It was done for y’all,” she tells the camera.

In 1978, HUD spent eight percent of the US federal budget. Now it accounts for about one percent. A Dream Deferred doesn’t point its finger at any particular elected officials; a hazy sense of “political gridlock” stands in for an explanation. To be fair, both Republicans and Democrats have so fully abandoned public housing in America that it’d be tough to know where to start when assigning blame.

In 1998, Bill Clinton signed into law the Faircloth Limit, prohibiting public housing authorities across the country from adding any new HUD-subsidized units from that point forward. NYCHA’s most recent development finished construction in 1997, and since then, New York City has grown by a million residents. The lack of new capacity at NYCHA has generated a homeless population in public housing’s common spaces, putting extra strain on the aging buildings. Even so, A Dream Deferred suggests that some NYCHA residents believe there is a path forward, and it starts with sharing their stories with the public.

No one should ever need a reminder that the more than 400,000 residents of NYCHA are human beings, but some people probably do anyway. Over images of dancing and basketball at the annual Seth Low Houses Family Day, Reginald Bowman describes the lively, joyful culture that exists in and around NYCHA’s brick towers. “We want people to know that this isn’t just a jungle. This is a place of human resources and everyday American life like any other community,” he comments.

A Dream Deferred begins with a title card: “For a year, we followed the lives of five residents in New York City public housing.” If so, the resulting footage was subject to strenuous editing, since the final running time barely exceeds 30 minutes. It would be nice to be able to get to know Bowman, Davis, Grant, Arrington, and Pearson better, but WNET’s concise, glossy video package is a worthwhile introduction to their neighborhood.

Viewers can stream A Dream Deferred for free at pbs.org/wnet/chasingthedream.