You’ve probably watched the annual spectacle on the local TV new stations or maybe have even participated in it yourself, dressing up in costume and walking the mile-long route in Lower Manhattan. New York City’s Village Halloween Parade is just one of those city-specific events that you can only experience here, much like the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade or the New Year’s Eve ball drop in Times Square. As the parade approaches its 46th year this month, we took a deep dive look into its longstanding history.

Bennington and the very beginning

To understand its immense popularity now, you have to revisit the parade’s past, which led us to speaking with puppeteer Ralph Lee, the original organizer. He had been working simultaneously as an actor and a mask maker prior to the parade; but in the spring of 1974, he was teaching at Bennington College (Bennington, Vermont) when he was asked to direct and produce an outdoor campus production.

“I had been making some big puppets – not a lot of them at that point, but I thought, ‘Should I do something that incorporates a lot of these puppets?’ and having the students make some as well,” Lee explained. “So I got this idea of doing an event that would take place at various locations on the Bennington College campus, and we [he and playwright Nancy Fales] developed this scenario of a young woman who is sort of on a search.”

“I had been making some big puppets – not a lot of them at that point, but I thought, ‘Should I do something that incorporates a lot of these puppets?’ and having the students make some as well,” Lee explained. “So I got this idea of doing an event that would take place at various locations on the Bennington College campus, and we [he and playwright Nancy Fales] developed this scenario of a young woman who is sort of on a search.”

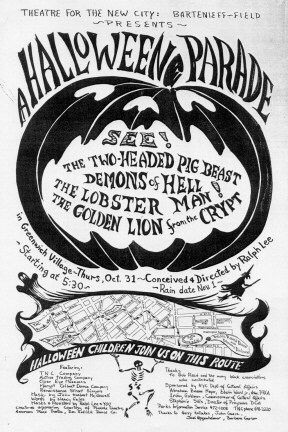

Excited audience members traveled along a certain route to various locations and experienced different scenes that involved puppets as characters. Lee included and featured, for example, a large lobster and a two-headed pigbeast that he had made specifically for Sam Shepard plays. He also made a giant lizard puppet, which he created with the students, crawl across the wall of enclosed garden.

“It turned out to be a very successful undertaking. It was the first time I’d seen my big puppets outdoors, and it seemed like this was where they really belonged, not indoors onstage in a theater,” Lee said. “I was really excited about this and began to think of ways of doing more theater outdoors.”

He later connected with George Bartenieff and Crystal Field, who ran the Theatre for the New City (where he had done previous work), and they decided to put on a community parade in Greenwich Village, where the theater was located and where Lee lived, on Halloween. Lee provided about 100 masks and big puppets and the Theatre provided some performers for the parade, which also had staged scenes along the route. Much like the Bennington College event, the idea was that the parade could momentarily stop so attendees could watch mini acts take place. It started at the Theatre for the New City, came over to Westbeth, went to Abingdon Square, down Bleecker Street for a while and then zigzagged over to Washington Square.

After finding success with it the first year with fewer than 200 participants, Lee organized another Halloween parade with Bartenieff and Field and discovered that local residents were really interested.

“At the end of the second year, I felt the parade needed to be its own organization, an entity of its own,” he said, later explaining that he started his own not-for-profit.

Subsequent parades became partially funded by the City, started at the Westbeth Community Room instead and became interspersed with musical groups like bands from Chinatown and from the Bread and Puppet Theater, which had worked with Lee for a number of years. Puppets were spotted in windows, on doorsteps and even flying off flagpoles. The parades continued to get bigger as years went on, with increasing local and international media coverage and with more people coming to watch and coming in costume to join Lee’s creations.

Lee’s apartment in Westbeth Artists Housing served as the central headquarters for parade planning and Lee decided it was time to step down in 1985. Jeanne Fleming, who came to work on the parade in 1983, became its director following his departure.

Handing over the reins

Before entering the spooktacular world of the Halloween parade, Fleming was a clothing designer, cooperative arts program creator for 30 colleges above New York City and the themed event curator at Mohonk Mountain House. But after a life-changing experience in the Sahara Desert, she decided to pursue the one thing she’d always wanted to do – create her own theater piece. Fleming developed a large-scale, outdoor pageant, held every October 4, during which attendees walked between various set pieces that had performances, music, dance, theater and storytelling. She told us that, after all the hard work of putting on her event, she’d always treat herself by attending the Halloween parade in Manhattan a few weeks later.

When she heard Lee didn’t want to spearhead the parade anymore, Fleming came down from upstate New York and brainstormed ways with him to keep it going. She met with the local community boards, City agencies and anyone else who was involved with helping the event run smoothly. Fleming noted to us that, over the decades, crowd sizes amassed from 15 to 20 thousand (spectators plus participants) to 2 million attendees and between 60 and 70 thousand participants now.

“The Halloween parade is an eccentric event,” she said. “I really see [it] as being about individual creativity but on a mass scale. It’s about each person coming out and what fantasy they decide to live in for that night – breaking out of everyday reality and being able to perform in this transformative environment.”

Traditions and themes

Fleming has stayed true to Lee’s vision and has expanded upon it too, as it now includes 53 different kinds of music from around the world, hundreds of master and volunteer puppeteers, and tens of thousands of participants from all different walks of life dressing up in creative costumes. One element that’s been the same since its inception, for example, is having the now-40-year-old dancing skeleton puppets lead the parade.

“What the dancing skeletons teach us and tell us is that life is short, so you better dance when you’re alive,” Fleming said. “They’re really the spirits of the parade.”

However, one component that was added about 25 years ago was providing a special theme. Fleming said someone had mentioned that it would’ve been helpful if the parade team could give people a little direction or creative inspiration when it came time for them to think about their next best costume. But just because the parade has a theme each year doesn’t mean you have to adhere to it; you can still dress up as whomever or whatever your heart desires.

The team usually discusses themes as early as May, but Fleming notes that the zeitgeist of the world can change it at any time. For instance, after the 9/11 attacks, the theme changed within seven weeks to “Phoenix Rising,” providing hope to New Yorkers when it became the first major event held in the City and showcased a huge phoenix puppet.

“We felt it was even more important to do [it] at that time. New York City has this spirit of continuing and a faith in humanity – it’s the same spirit as the Halloween parade,” Fleming said.

Other previous themes have also included: “I am a Robot” last year, “Revival” for the 40th anniversary and “Metamorphosis” for the 25th anniversary. But this year’s theme is “Wild Thing!” – a call back to nature when our lives are inundated with technology.

“We’re hoping people will go back to making things that are made out of natural materials or [dressing up] as things that are more based in nature,” Fleming added. “I think it’s going to be interesting to see because we’re going to have everything from kitties to pretty deep creatures. And I hear in Game of Thrones there’s a group called the Wildings; I would expect we’d get some wildings who live outside the walls of the palace.”

“We’re hoping people will go back to making things that are made out of natural materials or [dressing up] as things that are more based in nature,” Fleming added. “I think it’s going to be interesting to see because we’re going to have everything from kitties to pretty deep creatures. And I hear in Game of Thrones there’s a group called the Wildings; I would expect we’d get some wildings who live outside the walls of the palace.”

She and her colleagues also decided to have a new section in the parade last year, in which participants who dressed to the theme could march in a special part for $25. Additionally, those who wanted to be a VIP and get into the parade early could pay $100 to do so. One of the VIP perks is a participant choosing what band they would like to march next to for the whole night. These opportunities are available again this year. But just like it started in 1974, the parade remains free to watch and free to march in for those who dress in costume.

Where they are now

Although Lee is no longer involved with the Halloween parade, he and the Mettawee River Theatre Company (his own theater company) have staged the Procession of the Ghouls at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine’s Halloween Extravaganza since 1990. The extravaganza, which is always held on the Friday before Halloween, includes the showing of a classic silent film with live organ accompaniment; this year’s film will be Nosferatu (1922). The event concludes with Mettawee’s spooky costumed characters and puppets overtaking the Cathedral’s Nave in a display of sinister (but family-friendly) mischief.

The Village parade route itself has changed a couple of times through the last four and a half decades, but it currently runs straight up Sixth Avenue, from Spring Street to 16th Street (most crowded between Bleecker and 14th Streets). This year’s grand marshals are Zohra the Giant Spider puppet and its creator, Master Puppeteer Basil Twist. Zohra has gone up and down the famous clock tower of the Jefferson Market Library for the last 30 years.

Fun fact: the puppets are fabricated and assembled at Superior Concept Monsters’ workshop in Red Hook, New York. That’s upstate, not the Brooklyn neighborhood.

Top photo of masked figures at a parade in the 1980s, taken by Scott Laperruque.

Author

-

George Fiala has worked in radio, newspapers and direct marketing his whole life, except for when he was a vendor at Shea Stadium, pizza and cheesesteak maker in Lancaster, PA, and an occasional comic book dealer. He studied English and drinking in college, international relations at the New School, and in his spare time plays drums and fixes pinball machines.

View all posts

George Fiala has worked in radio, newspapers and direct marketing his whole life, except for when he was a vendor at Shea Stadium, pizza and cheesesteak maker in Lancaster, PA, and an occasional comic book dealer. He studied English and drinking in college, international relations at the New School, and in his spare time plays drums and fixes pinball machines.