The Gowanus Neighborhood Coalition for Justice (GNCJ), an advocacy group that formed in response to the city’s proposed rezoning of Gowanus, has joined forces with 350Brooklyn, the local affiliate of the international climate change organization 350.org. On May 9, GNCJ members shared their list of demands for Gowanus at 350Brooklyn’s monthly meeting at the Commons, a cafe and event space on Atlantic Avenue.

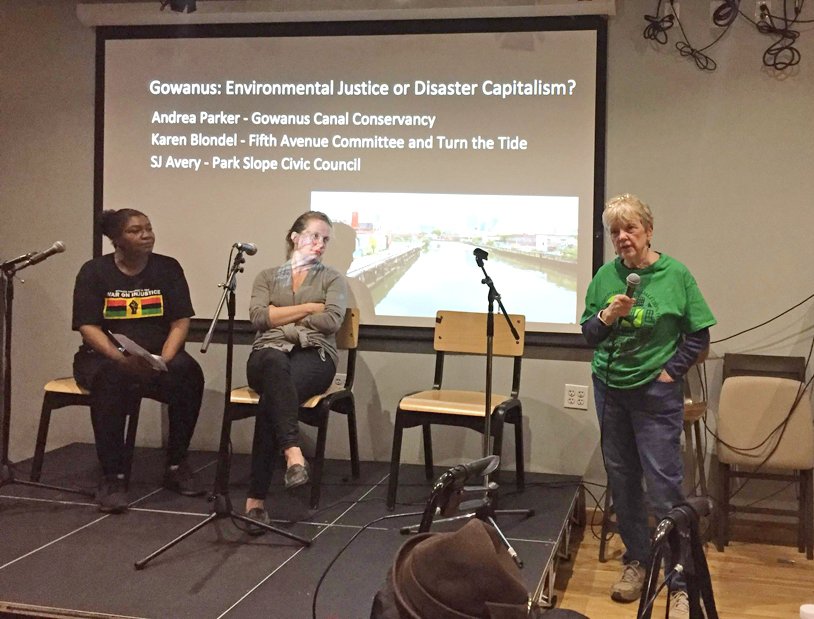

The Fifth Avenue Committee, a nonprofit developer of affordable housing, convened the GNCJ in 2017 to address questions of sustainability and gentrification as the city developed a plan to rezone industrial Gowanus for residential skyscrapers. Their environmental organizer Karen Blondel leads the group, alongside others such as Andrea Parker of the Gowanus Canal Conservancy and SJ Avery of the Park Slope Civic Council. For 350Brooklyn, the three offered a presentation titled “Gowanus: Environmental Justice or Disaster Capitalism?”

The author Naomi Klein coined the term “disaster capitalism” to describe the tendency of banks and corporations to make use of catastrophes and the resulting disorientation or desperation of their affected populations to engineer profit-driven takeovers of public assets. The disaster may be natural, like a hurricane, or manmade, like an economic collapse; in New York, a citywide housing crisis has, in the eyes of some critics, offered a pretext for developer-friendly upzonings of communities of color like East New York and East Harlem, paving the way for displacement.

“Zoning is a tool that has been used to enforce racism and disenfranchisement for decades,” Blondel proclaimed.

The GNCJ’s concerns include the nature of the affordable housing promised for the neighborhood (they want “deep affordability” and lottery priority for NYCHA and Community Board 6 residents) and the deterioration of existing public housing in the area. When the Department of City Planning (DCP) executes a neighborhood rezoning, the city typically promises a host of infrastructural upgrades to offset the population increase and community benefits to generate buy-in from the locals, but the boundaries of the Gowanus rezoning stop just short of the Gowanus Houses, Wyckoff Gardens, and the Warren Street Houses, which, like other NYCHA campuses, badly need repairs.

In recent months, the GNCJ has found a measure of local fame (or notoriety) by interrupting public meetings in Gowanus to insist upon NYCHA improvements, with particular emphasis on the promised reopening of the long-shuttered Gowanus Houses Community Center. “The fact that this rezoning is going on and there isn’t a place for Gowanus Houses residents to meet and talk about it is horrible,” Parker commented.

Furthermore, the GNCJ wants an upgrade for the public swimming pool at Thomas Greene Playground between Douglass and DeGraw streets, a community-wide emergency preparedness plan, newly planted trees to fill the holes in the “urban canopy” in previously nonresidential areas, and an improved waterfront access plan around the Gowanus Canal – which they hope the city will designate an “Environmental Special District” that, like the Special Natural Area Districts in Staten Island, would include zoning restrictions to protect the waterway as a habitat for wildlife and plants.

The GNCJ’s biggest worry, however, is sewage, which currently gushes untreated into the Gowanus Canal whenever rainwater overwhelms local sewers. The EPA – the federal agency overseeing the canal’s Superfund cleanup – has mandated that New York City build two wastewater retention tanks in Gowanus (or possibly a tank and a tunnel) to prevent overflows in the future, but according to them, the solution doesn’t account for the rezoning’s anticipated influx of new residents, who’ll add even more waste. {Editor’s note – in a response to City Planning’s Environmental Impact Statement, EPA reaffirms the city’s responsibility for the new CSO inflow). The city will face large fines if it allows new construction to negate the EPA’s solution to the wastewater problem, but it hasn’t yet committed to a solution.

Parker stated, “The city right now is saying, ‘We’re building infrastructure to manage sewage already. There’s no need to build any more.’ We’re saying, ‘We’re already promised that infrastructure. If you’re going to add more toilets to this watershed, we need to do a lot more.’”

The GNCJ advocates for the city to require developers to build their own digitally weather-sensitive retention tanks below their new high-rises, which would hold wastewater during storms and slowly release it afterward into the sewers. The activists also believe that internal water treatment systems could allow residential buildings to reuse their wastewater. (A few environmentalists in the audience grimaced at this suggestion.)

At the end of the meeting, the GNCJ distributed a stack of prewritten letters addressed to Olga Abinader, Acting Director of the Environmental Assessment and Review Division at the DCP, asking 350Brooklyn members to sign and mail them in support of the GNCJ’s goals. On March 29, the DCP released a Draft Scope of Work for an Environmental Impact Statement for the Gowanus rezoning. Until May 29, the public had a chance to submit comments with the hope of influencing the document’s final draft.

“The reality is that City Planning has been in discussion with developers for 10 years at least on this. This is not new to them. Our coalition is two years old. They have the advantage of the long game,” Avery said. In other words, the GNCJ needs all the help it can get.